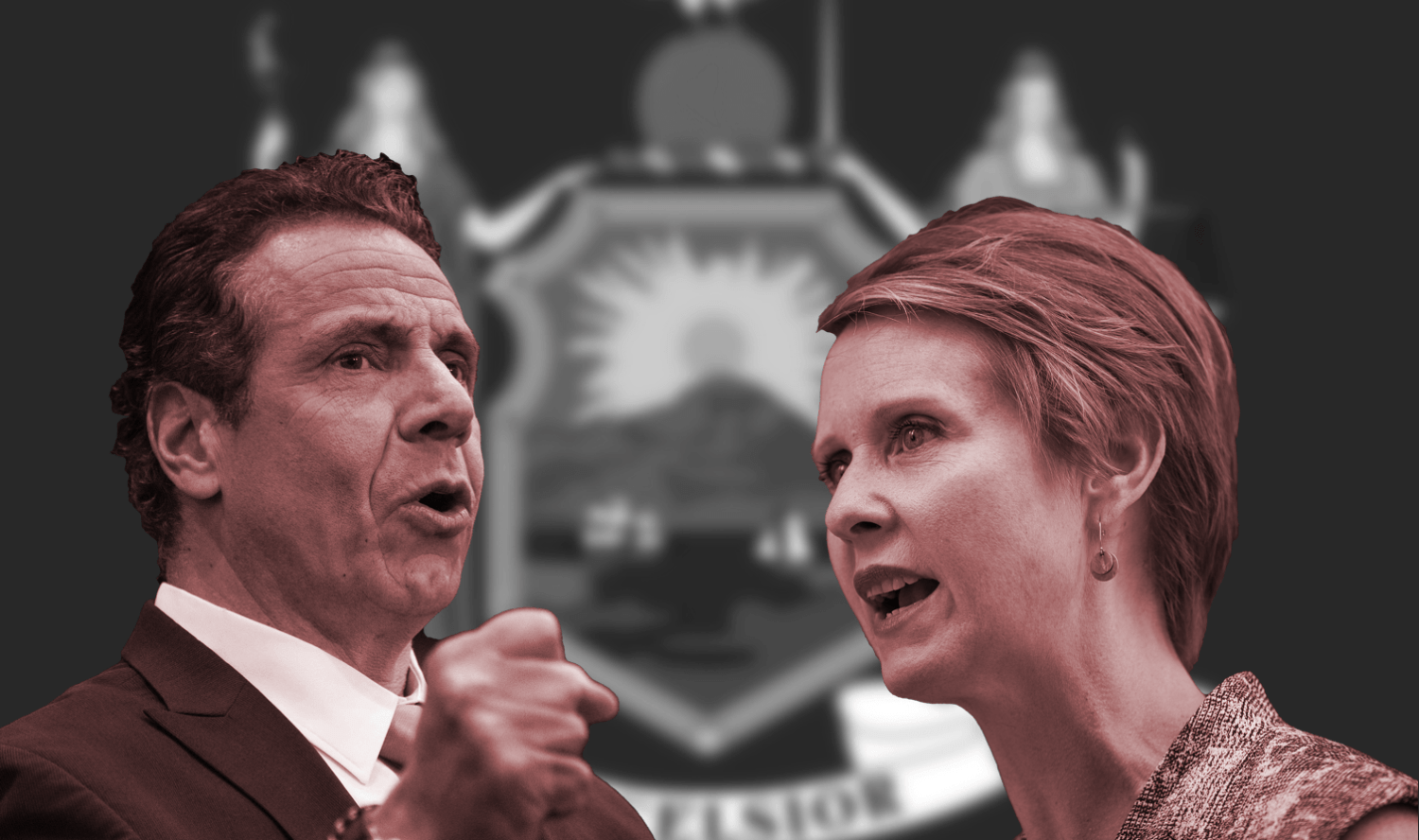

Here Are the Criminal Justice Issues Andrew Cuomo and Cynthia Nixon Should Debate

From policing to parole, this election could be pivotal for reform.

For advocate Bill Bastuk, Governor Andrew Cuomo’s sign-off on a prosecutorial conduct commission last week marked the culmination of nearly a decade of lobbying. Though funding and appointments have yet to be determined, the commission is designed to consider allegations of misconduct against any of the more than 60 district attorneys across the state. “The DAs did everything possible to squeeze him to veto this bill,” said Bastuk, who founded the nonprofit It Could Happen to You after his 2009 acquittal on charges of raping a 16-year-old girl. “I think what did send a message to the governor was this broad bipartisan support.”

For many criminal justice reform activists, the commission is a rare bright spot. New York recently became the 49th state in the country to raise the age of criminal responsibility to 17. It’s one of only 10 states where prosecutors don’t have to hand over most evidence to the defense until trial, and more than eight percent of the state’s prison population is in solitary confinement—close to double the national average.

So often with Cuomo, says Peter Goldberg, executive director of the Brooklyn Community Bail Fund, “We see measures that do something but don’t go nearly far enough.”

Now, in the lead-up to New York’s gubernatorial primary on Sept. 13, activists tell The Appeal that they have appreciated challenger Cynthia Nixon’s willingness to take their cues. “The sense that I’ve gotten is that she wants to sit down with the people most affected by this issue … and say, ‘Look, how can we fix this?’” says Nick Encalada-Malinowski, civil rights campaign director for VOCAL-NY. “Cuomo has certainly never sat down with people I know.”

Still, the criminal justice system in New York is so “devoid of any semblance of justice,” that truly effective reform will require looking beyond issues currently garnering headlines, said Steve Zeidman, a professor at City University of New York School of Law. For example, beyond the closure of Rikers Island and pre-trial reforms, he says he’s hopeful tomorrow’s gubernatorial debate will also touch on decarceral strategies like clemency and parole, which Nixon has brought to the fore, as well as human rights abuses at maximum security prisons across the state.

“The question is how high can we aim?” Zeidman said. “A governor can set a tone. They can use the bully pulpit, and say, ‘I’m going to keep talking about this issue until there’s a bill on my desk.’”

Policing

“Cynthia’s platform [is] cognizant that New York hasn’t taken even a measured step towards addressing the school-to-prison pipeline,” says Kesi Foster of Make the Road Action, explaining the nonprofit’s decision to endorse Nixon. He praises her for condemning metal detectors and police officers in schools; by contrast, last September, Cuomo announced the deployment of state troopers to 10 Long Island high schools he deemed a “breeding ground” for gangs including MS-13.

Overall, Foster added, Nixon “seems to acknowledge that there are longstanding structurally racist issues in policing.” She believes that recreational marijuana should be legal, while Cuomo has inched towards legalization without a full throated endorsement. . She also supports the repeal of Section 50-a of the New York State Civil Rights Law, which police departments use to justify withholding officers’ disciplinary records, as well as existing legislation that would make certain low-level offenses ticketable, rather than arrestable. Her platform highlights the Police-STAT Act, legislation that would require the state to track arrests by race, age, and gender; she supports codifying Cuomo’s 2015 executive order naming the attorney general as a special prosecutor in police killings, and would expand it to include cases where the civilian was believed to have had a weapon, or did not die despite the alleged use of deadly force.

Yet Hawk Newsome, president of Black Lives Matter of Greater New York, told The Appeal that the Black Lives Caucus has not endorsed a gubernatorial candidate and does not plan to. Stressing that he speaks for himself and not his organization, he bemoaned feeling “stuck between a rock and a hard place.” While the special prosecutor executive order could be strengthened, he said, Cuomo still “did something that was really helpful.” Meanwhile, Nixon hasn’t met with his organization, and he hasn’t seen her campaigning in the Bronx (Nixon’s team cited three visits to the borough, including a canvass kickoff in early June). “Cynthia is supposed to be anti-establishment candidate, but … we’ve been in the streets and I don’t see her people,” he said.

Pretrial

“We started off the legislative and budgetary state year with a lot of hope—hope for bail reform, hope for discovery reform, hope for speedy trial reform—and didn’t get anything,” Tina Luongo, attorney-in-charge of the Legal Aid Society’s criminal defense practice, stated earlier this month.

In January, Cuomo proposed ending cash bail for people charged with misdemeanors and nonviolent felonies. For the first time in his seven-year tenure, he also called for discovery reform, demanding that defendants have access to evidence including witness names and statements and grand jury testimony ahead of trial (New York is one of a minority of states whose discovery laws give prosecutors a significant advantage, considering 98 percent of felony arrests that end in conviction never make it to trial.) Yet while public defenders say they appreciate Cuomo elevating the issue, they were frustrated to see loopholes emerge, apparently at the behest of the powerful District Attorneys Association of New York. Cuomo ultimately passed over existing legislation that had the support of Legal Aid and the New York State Bar Association, insisting on a “right of redaction” of witness information for prosecutors. Discovery reform fizzled, as did speedy trial proposals.

Akeem Browder, brother of Kalief Browder, who took his own life after three years of incarceration at Rikers Island for a crime he did not commit, said he is endorsing Nixon because he thinks Cuomo is opportunistic. Cuomo brought Browder on stage during his State of the State address in January, and “made a promise to me in my brother’s name” to pass pretrial reforms, he recalled. After these reforms failed to materialize, Browder says, Cuomo’s counsel, Alphonso David, asked him to participate in an endorsement video for the governor. “If that’s not just insight into how he really feels about or communities,” Browder told The Appeal. (A Cuomo spokesperson blamed the Republican-majority state Senate for the failure of the reforms.) Now, he points to Nixon’s proposal to abolish cash bail regardless of the arresting charge, and her support of Kalief’s Law, a 2015 bill that would prevent prosecutors from dragging out pretrial detention with frivolous declarations of unreadiness for trial. “It’s time for a change,” he says.

Prisons

“I’ve heard Cuomo say time and and time again two things,” says Dave George, associate director of the grassroots group Release Aging People in Prison. “One, that we’ve raised the age of criminal responsibility to 18. And the second thing he says a lot is that he’s closed more prisons than any other governor.”

The former is an “embarrassment,” George argues, considering New York was among the last states to do so. The latter, while admirable—Cuomo’s office says he has closed 24 facilities in his tenure—excludes maximum and super-maximum prisons. A spokesperson for Cuomo’s re-election campaign confirmed to The Appeal that closing Rikers Island is a priority should Cuomo win a third term, along with pretrial and re-entry reforms. Similarly, Nixon’s platform states that she is “prepared to ensure that her administration … uses every available power to force the closure of all facilities on Rikers Island.”

“It’s critical for whoever occupies the Governor’s office to close upstate prisons, as well,” said Jared Chausow, a policy specialist at Brooklyn Defender Services, in a statement to The Appeal.

Cuomo announced a settlement with the New York Civil Liberties Union in 2015 intended to significantly reduce solitary confinement for teenagers, though a report from the Marshall Project in March found it’s still common practice outside New York City. Whereas Nixon has pledged to abolish solitary confinement by executive order for people of all ages, and codify it by supporting the HALT Solitary Confinement Act. Chausow notes that doing so shouldallow for the closure of New York’s two supermax prisons, Upstate and Southport.

Beyond abolishing solitary, there are needs for expanded medical care, mental health services, and recourse for survivors of assault by officers, activists said. They expect a lot of the governor, considering the Commissioner of the Department of Corrections and Community Service reports directly to that office. “It’s positive that [Nixon] has been raising a number of issues that are important to peoples who are incarcerated,” said one activist who requested anonymity in discussing electoral politics because they work for a nonprofit. “But there are other important issues that need to be addressed” in prisons “ripe with abuse, brutality, and racism.”

Clemency

At an event at the Fortune Society this month, Nixon called out Cuomo for his approach to clemency—including pardons, which expunge a person’s criminal record post-release, and commutations, which shorten or end sentences. “He is very spare with them, as opposed to say, someone like [Governor] Jerry Brown in California,” she said. Despite 2015 reforms expanding access to free legal counsel for clemency applicants, Cuomo has granted just 12 commutations since taking office. (His father, Mario Cuomo, issued 37 in three terms, The Appeal recently reported; Governor Brown once issued 19 in one day.) He has been more liberal with pardons, including more than 18 for New Yorkers at risk of deportation, and, conditionally, more than 100 for New Yorkers convicted of nonviolent crimes in their teens.

“We have 10,000 people serving life sentences, and that’s where the governor has to zero in on,” says Zeidman, who has filed more than 30 commutation applications with his CUNY Law students.

Nixon’s platform prioritizes commutation for all survivors of gender-based violence who are convicted after acting in self-defense. According to her staff, she was inspired by the work of Survived & Punished, a grassroots prison abolition group. Zeidman would like to see Nixon expand her commutation priorities beyond survivors of gender-based violence: a goal that is “both long overdue but also problematic” because other prisoners serving life sentences are implicitly excluded.

Parole

George, the associate director of RAPP, says Nixon’s interest in parole reform has been refreshing. “For a long time we’ve felt alone,” he says. “This issue is [historically] only brought up in really high-profile cases where the police unions and conservatives are against it.”

Nixon’s platform echoes recent RAPP recommendations to appoint more Parole Board commissioners with backgrounds in rehabilitation, like social workers and nurses. Cuomo appointed six new commissioners in this vein last June, and RAPP says release rates have since increased to 37 percent from 24 percent. Yet the board is still understaffed, with 12 commissioners out of a possible 19 overseeing 12,000 cases annually. Nixon has also singled out Commissioner W. William Smith, the board’s longest-serving commissioner, who Cuomo reappointed last year despite opposition from 19 senators. (Smith has a reputation for denying parole for those with violent crime convictions regardless of age, health status, and other factors.)

Cuomo’s election year gestures on parole reform have been fairly typical, as George sees it: “Big press releases, nice talking points, but not so much substantive policy.” This winter he proposed “geriatric parole” for gravely ill prisoners over the age of 55 who have served at least half of their sentences, with exclusions for certain criminal convictions. The legislation did not survive budget season. In April, Cuomo garnered positive headlines for an executive order restoring voting rights for parolees. But closer inspection shows it’s up to the DOCCS Commissioner to submit a list of parolees monthly to the governor’s office. Voting rights are then granted on a case-by-case basis.

By contrast, Nixon has endorsed existing legislation that would empower the board to assess every prisoner over the age of 55 who has served 15 years. “It’s great, but it’s tepid,” says Zeidman, who would like to see parole hearings for all prisoners who have served a chunk of their sentence, regardless of age. “Go further.”

Correction: This story has been updated to note that the governor’s office, not DOCCS, decides which parolees will be granted the right to vote.