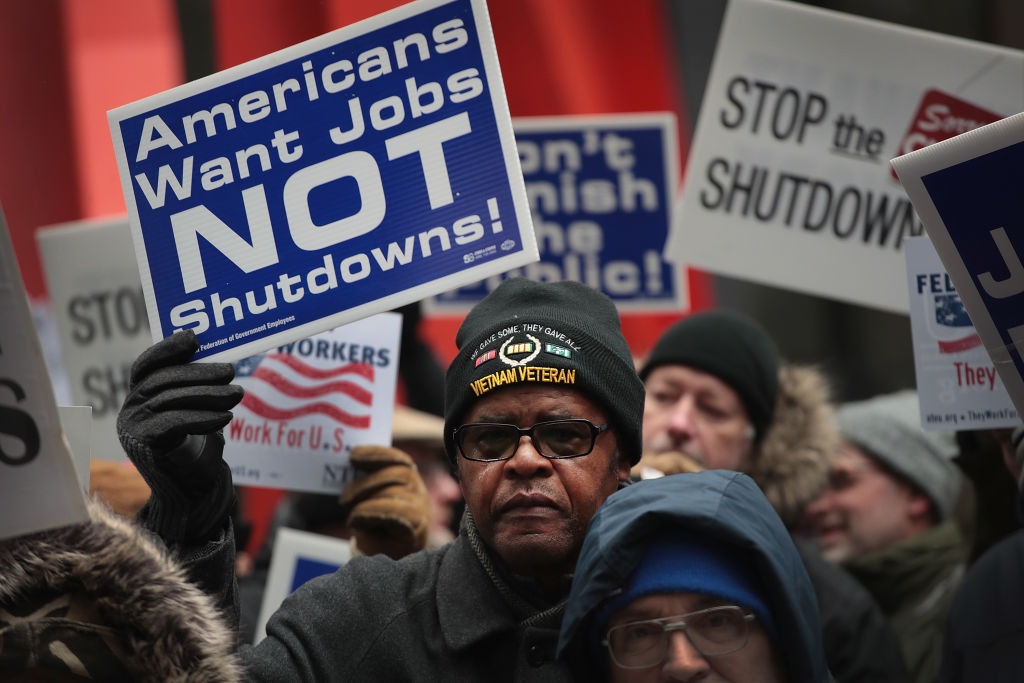

‘The Sixth Amendment Doesn’t Shut Down When the Government Does’

Federal defenders say the shutdown is hurting poor people stuck in jail.

As the government shutdown extends over a month with no end in sight, public defenders say their clients are being denied access to justice due to staffing shortages in federal jails and courts.

New York assistant federal defender Jennifer Willis told The Appeal that she and her colleagues have been barred from visiting clients in jail because of the shortages.

Willis has one client in custody in Brooklyn’s Metropolitan Detention Center awaiting sentencing. Before that can happen, Willis needs to schedule a mandatory interview with her client and a probation officer, which will allow the officer to conduct an investigation into her client’s case.

But on the day of the scheduled interview in early January, she discovered that the jail was closed to legal visits. Willis and the probation officer rescheduled for the next week, but when she got to the jail, she said, there were signs on the doors saying the facility was still closed.

“In order to make sure the sentencing goes ahead on time, the interview has to happen on time,” Willis said.

The Bureau of Prisons confirmed the closures, telling The Appeal that legal visits in Brooklyn and Manhattan have “intermittently been temporarily suspended.” Wardens, the agency explained, “all have options to address any institution-specific concerns” during the shutdown, including curbing or cancelling visitation.

She has not yet rescheduled the visit because it’s unclear when the facility will reopen. David Patton, executive director of Federal Defenders of New York, said the jail in Brooklyn has closed to attorneys for at least a portion of the day eight times this month. Similarly, Manhattan’s federal jail has suspended legal visits six times.

“It’s not a sustained shutdown, but frankly the biggest problem with it is the uncertainty of it,” Patton said. “We basically find out every day in the morning whether they’ll be having legal visits.”

Willis is planning to ask the judge for time served for her client, meaning he could be released on the date of his sentencing. If the jail continues to prevent legal visits, she said her client will end up in custody for additional weeks or months.

“It’s possible that we’ll have to write to the judge and request at least a short adjournment of my client’s sentencing,” she said.

The biggest problem with it is the uncertainty.

David Patton executive director of Federal Defenders of New York

Not only are the periodic shutdowns hurting attorney-client relationships, but they are a violation of individuals’ right to counsel guaranteed by the Sixth Amendment, Patton said, adding that his office is considering legal action.

Individuals in New York detention centers are just a fraction of the growing number of defendants across the country who are being adversely affected by President Trump’s insistence that a funding bill include $5.7 billion for a U.S.-Mexico border wall. While courts have managed to extend funding for federal defender agencies a week at a time, the funding is not expected to last past Feb. 1. Public defenders and investigators who are members of Criminal Justice Act (CJA) panels—groups of court-approved attorneys who are appointed on a rotating basis to represent people in criminal cases—are working without pay. So are lawyers with Washington, D.C.’s Public Defender Service.

“Members of the CJA panel and my office are essential to the proper functioning of the Sixth Amendment,” Jason Hawkins, the federal public defender for the Northern District of Texas, told The Appeal in an email. “We will continue to investigate our cases, appear in court, and defend our client [sic] against the awesome power of the federal government. Yet we will not be paid.”

Hawkins and other federal public defenders say they are concerned that many of their clients will be held in custody for longer than necessary.

“The Sixth Amendment doesn’t shut down when the government does,” he said.

An extra night in jail

Because U.S. Marshals are working without pay, magistrate judges across the country are taking steps to accommodate staffing shortages and the fact that they may need to work second jobs. In the Southern District of New York, the chief judge told magistrate judges to cut back on when new cases can be processed.

Typically, individuals who arrive at the Manhattan court before 4:30 p.m. will have their cases presented in front of the magistrate that day, allowing the appointment of a federal public defender and a determination of bail. On Jan. 9, however, the chief judge issued an order stating that “because of the lapse of funding to the U.S. Department of Justice, including the United States Marshals Service,” the cutoff for first appearances would be moved to 3 p.m. starting the next day.

In order to meet that deadline, Willis said individuals would have to be in the door before 1 p.m. to allow time for processing. Because court marshals are typically accustomed to bringing defendants in by 4:30 p.m., she expressed concerns that people would miss the new deadline. “If you don’t make that cutoff, that means you’re going to be held overnight,” she said. “[That includes] somebody who might have otherwise been bailable—to get bail and go home—so there’s a lot of scrambling.”

Judges are mindful of the fact that there’s constitutional rights at stake and people’s liberties at stake, but there’s been a lot of push and upheaval.

Jennifer Willis New York assistant federal defender

Under the order, magistrate judges can still choose to allow appearances later into the afternoon. According to Patton, most have accepted late arrivals rather than holding people overnight.

“Judges are mindful of the fact that there’s constitutional rights at stake and people’s liberties at stake, but there’s been a lot of push and upheaval,” Willis said.

For at least one client, Willis said she had to rush through his intake and didn’t have time to do the type of thorough work that she typically conducts. “That kind of rush is not something you want to have happening,” she said.

The U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern of District of New York did not respond to a request for comment (most of the press office is furloughed, a representative said). John Marzulli, public information officer for the Eastern District of New York, said business continues as usual in Brooklyn during the shutdown.

“We’re not receiving a salary, but we’re working,” he said.

Federal defenders questioned whether that’s the right strategy.

“From our perspective,” Patton said, “the answer to the fact that law enforcement doesn’t have the funding to operate normally isn’t to keep arresting and prosecuting the same number of people and just operating business as usual, and then giving them short shrift on process and detention conditions. It’s to scale back on cases.”

‘I might decline cases if I don’t know what’s on the horizon.’

The uncertainty in the jails and courts extends to CJA attorneys, who have been working without pay since the start of the shutdown. Camille Knight, the CJA panel representative for the Northern District of Texas, told The Appeal that nobody is shirking current cases, but it’s likely that some CJA attorneys will decline to take future clients knowing the work would be unpaid for the indefinite future.

“There are many panel members who do other work also and if the choice is take a case at an already-discounted hourly rate or do something else, they’re going to do something else,” she said. “I might decline cases if I don’t know what’s on the horizon.”

Knight said the shutdown is also impacting her interaction with clients. Attorneys on her panel have had trouble scheduling legal visits with the Bureau of Prisons and have advised one another to schedule jail visits as soon as they can because they could be cut off at any point, like in New York.

“There was some anecdotal advice going around last week that people should try to go visit their clients when they could because there may be some blue flu going around the BOP,” she said, explaining that jail employees could begin calling in sick en masse, as Transportation Security Administration employees and other unpaid federal workers have done.

The shutdown is also affecting detainees’ personal lives. As the New York Times reported, social visits are also blocked at jails in Manhattan and Brooklyn due to staffing shortages. Some individuals in Manhattan’s federal jail started a hunger strike last week, the second straight week without visits.

“What has been most difficult for clients has been the impact on social visits,” Willis said. “Legal visits are necessary and required and we can’t possibly move forward with a case unless lawyers have access to their clients, but it’s really important for them to be able to see their families.”

The prolonged uncertainty has created even more instability in her clients’ lives, she said.

“It’s very nerve wracking and disconcerting for people to not know what’s going to happen to them,” Willis said. “Are they going to meet with their lawyer? Are they going to be able to get their medication? Are they going to be able to see their family? And it’s day to day—maybe today you get a visit, maybe today you don’t. It’s very concerning.”