For Many Prisoners, Mississippi’s Habitual Offender Laws Are Like ‘Death Sentences’

One man, Paul Houser, is serving 60 years on a drug conviction for purchasing cold medicine and batteries. He’s one of 2,600 people incarcerated as a result of the state’s three strikes laws.

At 56 years old, Paul Houser knows he will most likely die in a Mississippi prison. He arrived there in 2007, a year after police pulled him over and discovered he had purchased six packs of cold medicine and four lithium batteries, ingredients they said were to be used to make methamphetamine. His first trial ended in a mistrial. On the prosecution’s second attempt, a Lowndes County jury convicted Houser of possessing methamphetamine precursors.

It wasn’t his first run-in with the law. He was also convicted of possessing methamphetamine precursors with the intent to manufacture in 2002, and in 1983, at the age of 19, for selling marijuana. Under the state’s habitual offender laws, otherwise known as three strikes laws, a person convicted of a third felony can be harshly punished, regardless of the severity of the crimes. In Houser’s case, his previous convictions meant that Forrest Allgood, district attorney for Mississippi’s 16th Judicial District, could seek the maximum sentence allowed for his crimes: 60 years. Allgood, who was known for his aggressive prosecutions, seized the opportunity.

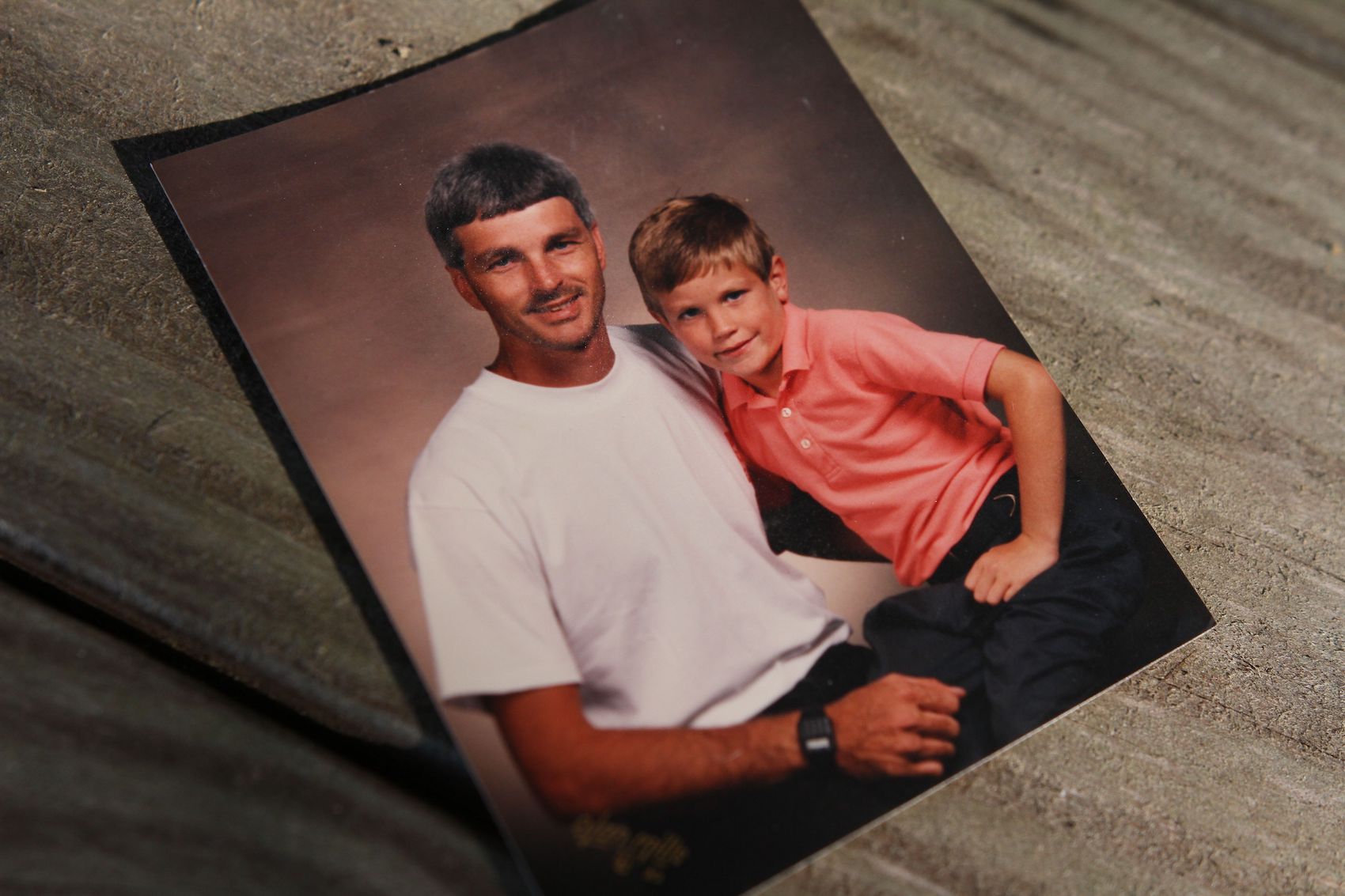

“I was really in shock … I couldn’t believe it,” Houser’s son, Dusty Houser, told The Appeal of the sentence. “At the beginning I couldn’t grasp it, but now it’s been 13 years and it’s been hard. It’s heartbreaking how much he’s missed out on stuff.”

In the months following the trial, Dusty said two jurors told him that they never would have voted to convict had they known he would receive such a long sentence.

Houser is set to be released from prison in 2067 at the age of 103. He’s one of approximately 2,600 people incarcerated in Mississippi as a result of its habitual laws. Of those, one-third have received sentences of 20 years or more, and half of that group, 439 people, have been sentenced to die in prison through sentences of either life without the possibility of parole or of more than 50 years, according to a November report from FWD.us, an advocacy group. And in a state where 38 percent of its population is Black, 75 percent of the people sentenced to 20 years or more under habitual laws are Black men, FWD.us’s research shows.

In addition to Houser, there are 77 people in the state’s prisons sentenced as habitual offenders to 50 years or longer for drug crimes alone. Critics say the laws are being used to unfairly punish people and drive the state’s already high prison population upward. Mississippi has the third-highest incarceration rate in the country, behind Oklahoma and Louisiana. Still, as opposition to the laws grows, including rebukes from faith leaders and conservatives, the state has done little to change its use of the punishment.

“Sometimes they add so many years, they’re death sentences,” the Rev. Wesley Bridges, executive director of Clergy for Prison Reform, told The Appeal. “We think they’ve been designed as barriers to keep the prison pipeline flowing.”

People can be convicted under Mississippi’s habitual laws in one of two ways. Houser was sentenced under a law which says that any person with two felony convictions is required to be sentenced to the maximum term allowed for their third offense. For possession of methamphetamine precursors, that was 60 years.

A second law says anyone who has two previous felony convictions, including one considered “violent,” must be sentenced to life without the possibility of parole. The state’s list of violent crimes is long and includes offenses that might not result in injury such as driving under the influence and burglary.

“If you break into someone’s home, you committed a crime of violence … it doesn’t matter if anybody’s home,” Jake Howard, an attorney with the MacArthur Justice Center who has represented people convicted as habitual offenders, told The Appeal. “It doesn’t matter how long ago it was. I could’ve committed it when I was 15 and committed the third felony when I was 65.”

A person is not automatically tried as a habitual offender for their third offense, however. That decision lies with the district attorney, who has the discretion to seek the maximum sentence. But the mere existence of habitual laws can have a chilling effect. Prosecutors can use the threat of a harsh sentence in plea bargaining, which may force innocent people to plead guilty to avoid a decades-long prison sentence. It’s unclear how many people in Mississippi are incarcerated as an indirect result of the laws.

State Senator Derrick Simmons has long been aware of the way habitual laws have impacted people, especially Black men, across the state. For years, he has introduced legislation aimed at curbing the laws, only to have it die in committee. His bills have never made it to the floor for a vote due to Lieutenant Governor Tate Reeves’s efforts to block the legislation, he told The Appeal. Reeves is the president of the Senate.

Reeves did not return requests for comment from The Appeal.

Among the reforms that Simmons has attempted to pass is the establishment of a two-part trial for people being tried as habitual offenders. Similar to a death penalty trial, a jury would get to consider evidence relating to a person’s background, such as their age or life circumstances at the time of their crimes, before voting for the maximum sentence allowed under habitual laws. A different bill that Simmons has introduced would require both previous offenses to be crimes of violence. And another would mandate that the two prior felonies be committed within 10 years of the sentence.

“The prison population in Mississippi is marching upward and there are disparities in sentencing,” said Simmons. “Policies regarding criminal justice have not treated all American citizens, and in my case Mississippians, equally or fairly and so it’s my hope that we can address some of this.”

State lawmakers have not been completely dormant on habitual laws, though their actions have been reserved for a small minority. In 2014, the state passed a bill aimed at reforming its criminal justice practices. As part of that bill, the sentence for Houser’s crime, possessing methamphetamine precursors, was reduced to eight years. That legislation did not affect people sentenced prior to 2014, however.

The legislation did offer Houser a different chance to win his freedom. Because all of his crimes were nonviolent, he can ask the judge who sentenced him to make him eligible for parole after 15 years, or 25 percent of his sentence. The judge is the sole decision maker on parole eligibility, and if he grants it, Houser would then have to petition the parole board for release. If the judge denies it, the decision can’t be appealed but there are no limits on how many times Houser could ask the judge to make him eligible.

There are 1,300 people who can one day petition for parole eligibility under that legislation. Jade Morgan, a Southern Poverty Law Center attorney who works on habitual cases, estimates that more than 60 people have already applied in Lowndes County and judges have denied all of them. She added that it’s rare for a judge to grant those petitions. Of the approximately 40 people she has represented across the state in the past year, only five have been made eligible. “The best thing we can do is try to change the laws so it won’t be left to a judge’s broad discretion,” she said.

For now, Houser is incarcerated at the Mississippi State Penitentiary, also known as Parchman Farm. The prison is known for its rampant violence, so Houser told his family not to visit. Dusty hasn’t seen his father, who he said is partially deaf and blind, in two years. The separation has been devastating, he said.

“I understand you do the crime you do the time but I feel like 13 years was sufficient for what he was caught with,” Dusty said. “I also feel anger toward the justice system because I know that’s just an ungodly amount of time. My dad would rather die than spend another day in that hell that he lives in.”