Federal Prisoner Set To Be Executed Next Week Was Labeled A ‘Psychopath’ Because Of A Faulty Evaluation Tool

A government psychologist who used the tool to evaluate Daniel Lewis Lee—who is scheduled to die Monday in Indiana—has since disavowed it. Without it, the trial judge has written that it’s ‘very questionable’ Lee would have been sentenced to death.

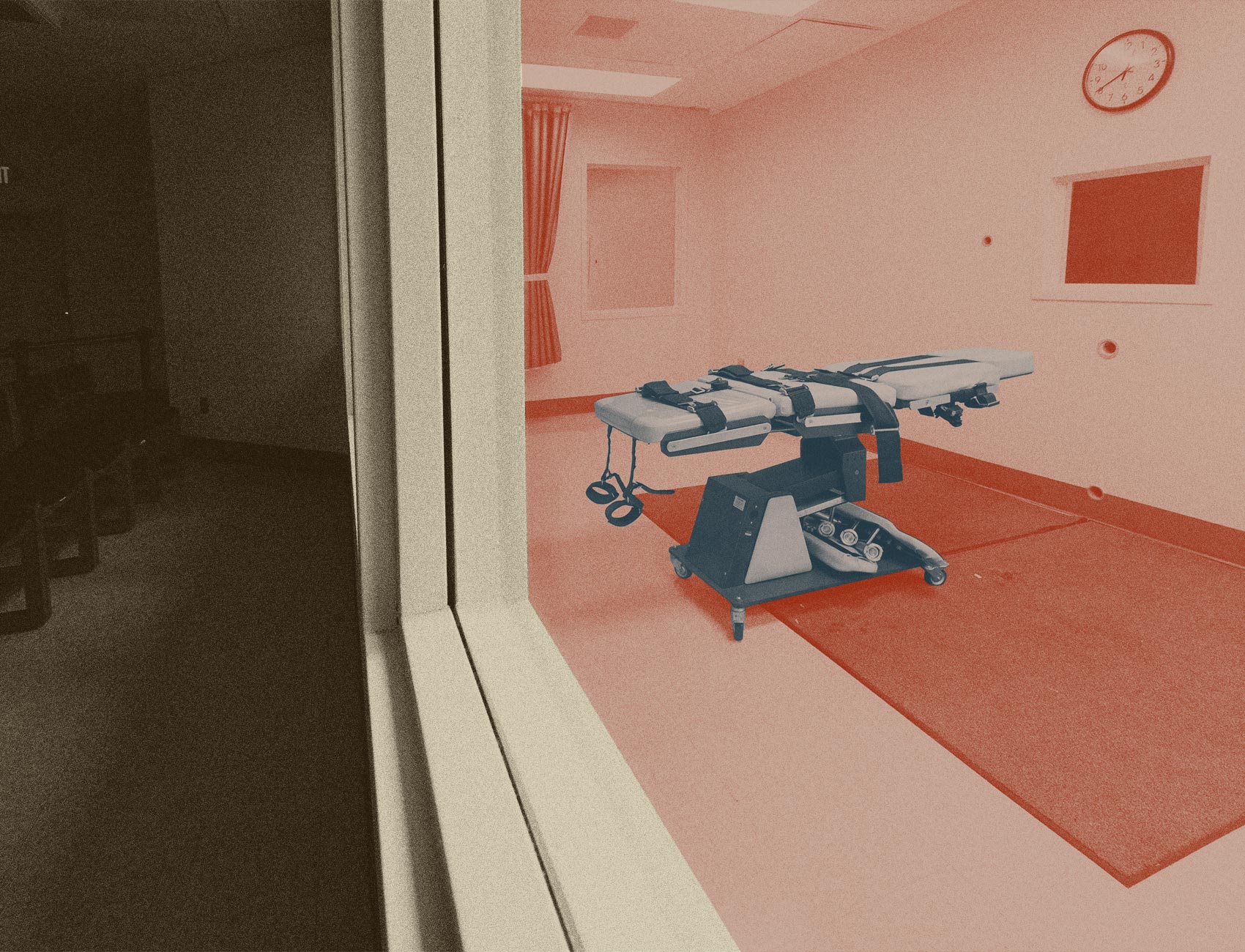

On Monday, Daniel Lewis Lee is set to become the first federal prisoner the government has executed since 2003.

In 1999, Lee was sentenced to death for the murders of an Arkansas family as part of a plot to fund and promote a white separatist organization that his co-defendant, Chevie Kehoe, started in Washington. Even though the prosecution argued that Kehoe was the ringleader and most culpable for the deaths, Lee was the one sentenced to death in part because prosecutors had branded him a “psychopath” based on the results of a notoriously unreliable psychological evaluation tool called Hare Psychopathy Checklist Revised (PCL-R). That tool has since been renounced by many experts and is generally not used in federal capital cases. Lee’s attorneys say he is the only person on the federal death row whose sentence relied on it.

Lee and Kehoe were accused of murdering William Mueller, his wife, Nancy Mueller, and her 8-year-old daughter, Sarah Powell. The same jury that sentenced Lee to death sentenced Kehoe to life without the possibility of parole days before Lee’s sentence was handed down. While Lee was awaiting sentencing, prosecutors asked the U.S. Department of Justice to remove the death penalty as an option for punishment. The Muellers’ family agreed. There was testimony that Kehoe had murdered Sarah after Lee, whom prosecutors described as Kehoe’s “faithful dog,” said he could not kill a child. But the DOJ rejected the request and prosecutors forged ahead with their case.

Armed with expert testimony that relied on the findings of the PCL-R evaluation, federal prosecutor Lane Liroff told the jury that Lee, then 26 years old, emblazoned with Nazi tattoos, and missing an eye from being hit with a billiard ball, would be a danger to everyone in prison should he be sentenced to life. Earlier, Liroff had elicited testimony from the expert who said that people who score high enough on the evaluation “do not appear amenable to treatment.”

Liroff hammered on this point in his closing statement, telling the jury, “Even if jailed for the rest of his life, he still will be a danger to others, to fellow inmates, to prison guards. He continues to be dangerous.”

Since he was sentenced to death, Lee’s attorneys have challenged both his conviction and sentence. They have charged that Lee’s trial counsel was inadequate in its challenges to testimony about Lee being labeled a psychopath, ultimately leading to his death sentence. They have charged that Lee was innocent and the government withheld crucial information. And they have charged that the ground that Lee’s conviction stood on has crumbled.

In June 1996, the bodies of the Muellers and Sarah were pulled from the Illinois Bayou, a stream an hour away from their home that runs south of the Ozarks. Investigators zeroed in on Kehoe and Lee a year later after Kehoe’s brother, Cheyne Kehoe, implicated them while turning himself in for shooting at police officers in Ohio. Soon, the case hinged on Cheyne and his mother, Gloria Kehoe, who were the star witnesses at trial. They both testified that Chevie Kehoe and Lee had confessed to killing the family, with Lee killing Bill and Nancy, and Kehoe killing Sarah.

During their joint trial, the prosecution alleged that Kehoe and Lee traveled from their homes in Spokane, Washington, to Tilly, Arkansas in January 1996. Kehoe and his family knew Bill, who was a federally licensed gun dealer, from gun shows where he sold firearms, ammunition, and books about “survivalist” practices. They had also bonded over their shared anti-government views—Bill often talked about exchanging his currency for gold, stockpiling weapons and food, and getting “off the grid” with his family, according to trial testimony. Prosecutors said that Kehoe was also already familiar with the Mueller home and its wares—he and his father had broken in and stolen weapons and cash in 1995. Believing there was more property at the home, Kehoe had convinced Lee, who had met Kehoe in 1995, to return to Arkansas with him and burglarize the Muellers again, according to the government.

This time, Kehoe and Lee allegedly dressed themselves in FBI raid gear and waited for the Muellers and Sarah to return home. When they did, the pair pretended that they were conducting an FBI raid, according to the prosecution’s theory. After they were led to $50,000 in cash, guns and ammunitions, Lee and Kehoe incapacitated the family with a stun gun, taped plastic bags over their heads, and eventually dumped the bodies over a bridge in the bayou, prosecutors said.

Monica Veillette was 19 when she testified for the government about the murders of her cousin Sarah and aunt Nancy. Prosecutors had alleged that Lee and Kehoe violated the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, also known as RICO, and the deaths were a key part of the case that had been built against them.

Prosecutors used Veillette’s testimony to establish a timeline of the family’s disappearance and identify a jewelry box found in Kehoe’s possession. When she finished testifying, Veillette attended the remainder of the trial with her mother, Kimma Gurel, and her grandmother, Earlene Peterson. Though she and her family did not want Lee to face the death penalty, Veillette told The Appeal last month that she wasn’t surprised when the jury voted for him to die and not Kehoe, who looked like the “boy next door.” His teachers testified to his intelligence and that he was deserving of life. Lee, on the other hand, was presented as “someone who was dangerous, who basically had no redeeming qualities,” she said.

“It made no sense to us that Daniel Lee would get the death penalty when Chevie Kehoe did not,” Veillette told The Appeal. “It was also obvious to us when [Lee] got the death penalty why that was.”

The PCL-R, the tool that was used to label Lee a psychopath, is among several psychological tests that have been found to be unreliable in criminal cases. In January, 13 expert psychiatrists and psychologists criticized the test, releasing a statement concluding that it “cannot and should not be used to make predictions that an individual will engage in serious institutional violence with any reasonable degree of precision or accuracy, especially when making high-stakes decisions about legal issues such as capital sentencing.”

The tool consists of 20 items designed to measure so-called psychopathy, such as lack of remorse or guilt, impulsivity, and pathological lying. In Lee’s case, the government’s expert, psychologist Thomas Ryan, administered the test, but the prosecution presented its results through the defense expert, Mark Cunningham, during cross examination.

Cunningham did not administer his own PCL-R because he felt he did not have all of the information necessary to properly evaluate Lee. Instead, prosecutors asked him about Ryan’s report, and Cunningham ultimately told the jury that Lee had scored high enough to be labeled a psychopath. Soon after, Ryan took the stand and confirmed that the test results were “valid and accurate,” according to court filings.

In a different death penalty case a year later, however, Ryan withdrew a report based on the PCL-R after defense experts pointed out that there was no scientific proof linking future dangerousness in prison with the test. In another case, he wrote in an affidavit that it “was not and still is not possible to conclude to a reasonable degree of scientific certainty … that a correlation exists between the PCL-R scores and federal prison violence.”

The use of the test had been deemed problematic by the trial judge in Lee’s case, too. A year after Lee was sentenced to die, Judge G. Thomas Eisele granted a motion for a new sentencing phase of Lee’s trial based partly on the assertion that prosecutors had overstepped with their presentation that he was a danger to others. That order was eventually reversed by the Eighth Circuit. But without the diagnosis, Eisele has written that it’s “very questionable” that the jury would have been swayed to vote for a death sentence.

Since then, Lee has appealed his death sentence on the basis of the use of PCL-R. In 2013, two expert psychologists, including the then-president of the American Psychological Association, signed affidavits as part of Lee’s appeals stating that there was no evidence supporting the use of the test to predict future prison violence at the time of Lee’s 1999 trial.

And though Eisele acknowledged that it’s likely Lee would not have been sentenced to death without the test, and granted a new sentencing hearing partly because of it, Lee has yet to succeed on the claim that his trial lawyers were ineffective. These denials have been based on procedural issues such as improper filing or filings that were made too late, according to Lee’s attorneys.

Robert Dunham, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center, told The Appeal that tests such as the PCL-R have a long history of problematic use in capital cases. “If you tell a jury that a person scores high on the scale of psychopath then you are going to produce a fear response form the jury,” he said. “You are going to activate all of the Hannibal Lecter detectors in their brains and you are going to elicit an irrational assessment of whether that person will pose a legitimate risk if imprisoned.”

“Prosecutors love it because it gets them the outcome they want,” he added.

Lee’s attorneys say they have uncovered evidence that shows that Lee was never involved in the murders. Among these, they say the government withheld a polygraph test implicating another man in the murder. That man was an original suspect and an associate of Kehoe’s father, according to Lee’s attorney.

Lee’s legal team obtained the polygraph test in January through a public records request. It showed that the man had failed questions about whether he had a part in killing the Muellers. In a report dated January 21, 1997, the polygraph examiner wrote that it was their opinion that the man “was involved in the death of the Muellers.”

Further adding doubt to the government’s case, a hair retrieved from an FBI cap in Kehoe’s vehicle—the lone piece of physical evidence tying Lee to the crime scene—did not actually belong to Lee, a 2007 DNA test found. A government expert had testified during the trial that the hair was microscopically similar to Lee’s, another form of forensic science that has since been scrutinized. Last month, Lee’s attorneys asked for a judge to order that DNA be compared to samples taken from the man who underwent the polygraph test and other suspects in the case.

Lee’s attorneys also say that the two key witnesses—Gloria and Cheyne Kehoe—received incentives to testify. Charges against Gloria for using a fake Social Security number were dismissed and she was paid $2,250 per month from the government for about a year, a total of $27,000 throughout the course of her cooperation, court documents show.

Cheyne was on the FBI’s Most Wanted list for the attempted murder of two Ohio police officers in a shootout, and investigators also believed he was part of the Kehoes’ racketeering enterprise. His 24-year sentence for the Ohio shootings was reduced to 11 years, and he received immunity for any charges connected to the racketeering case.

Despite this new evidence, Lee has been unsuccessful in his appeals largely because the evidence was considered by the courts as being submitted too late.

In 2014, the trial judge, Eisele, and the lead trial prosecutor, Dan Stripling, wrote letters to the Department of Justice as part of a clemency application Lee filed with the Obama administration. Eisele affirmed the dubiousness of the PCL-R and said that he had “frequently second-guessed” his decision-making in the case. “The end results leaves me with the firm conviction that justice was not served in this particular case, solely with regard to the sentence of death imposed on Daniel Lewis Lee.”

Stripling wrote that he was disturbed by the arbitrariness in which people are charged, convicted, and sentenced in capital cases and thought that the DOJ should have withdrawn its intent to seek death against Lee.

In a telephone interview with The Appeal last month, Stripling reiterated that he still believes Lee was involved in the Mueller murders. When asked about the polygraph test, he said he didn’t remember it and couldn’t believe it was never handed over because they had a full-time staffer handling documents for the defense. But he still stands by his letter. “I don’t like the death penalty,” he said. “I don’t like the way that the decisions are made about who to seek the death penalty on. I particularly didn’t like this case.”

The government had planned to execute Lee last winter but it was suspended because of challenges to a new execution method adopted by the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP). A federal appellate court cleared the way for executions to proceed in April and in June, the DOJ announced that Lee would be the first of four men to be executed this summer.

“We owe it to the victims of these horrific crimes, and to the families left behind, to carry forward the sentence imposed by our justice system,” U.S. Attorney General William Barr wrote in a press release announcing the executions.

But Veillette, speaking on behalf of her family, said that is not the case. Since Kehoe was sentenced, they have opposed executing Lee and advocated for his sentence to be commuted to life without parole. “They speak as if they are speaking for us and so it’s like stealing our voice and misrepresenting us, and Nancy, and Sarah, about who we are as people,” she said.

There is litigation still pending in Lee’s case that may halt Monday’s execution, but if it does move ahead, Veillette and her family are planning to attend so they can make their opposition known. Peterson, Nancy Mueller’s mother, will be driven 500 miles from Arkansas to the federal death chamber in Terre Haute, Indiana, because COVID-19 has made it too risky for her to fly. Veillette and her mother are also planning to attend against the wishes of their physicians.

Earlier this week, Veillette’s family filed a lawsuit seeking to block Lee’s execution on the basis that the government had put their lives at “grave risk” by scheduling the execution during the COVID-19 pandemic.

This morning, Judge Lee P. Rudofsky denied to postpone the execution because of COVID-19, writing that neither Congress nor the president has stepped in to stop executions during the pandemic. “I am not in good conscience going to substitute my weighing of the advantages and disadvantages for theirs—especially when a delay would have to be a long one to do any good,” his order reads.

In an email to The Appeal, a BOP spokesperson outlined the precautions the agency will take against the disease at the execution, including issuing face masks to everyone in attendance. Additionally, the spokesperson wrote that social distancing of six feet should be practiced but “may not be feasible based on the limited capacity of the media witness room.”

On the telephone last month, Veillette said she felt as if her family was ignored from the time that the DOJ refused to remove the death penalty as a possibility for Lee. She remembered her aunt Nancy, whom she described as a “carefree happy person” who loved to ride horses and play music. Sarah, she said, took after her mother, and was a curious child who wanted to work with animals one day. Both were compassionate and would not have wanted Lee to be executed, Veillette said.

“To have their stories end with such a horrific act done in their name does them a disservice,” she said. “We don’t want that to be the last chapter in their story.”