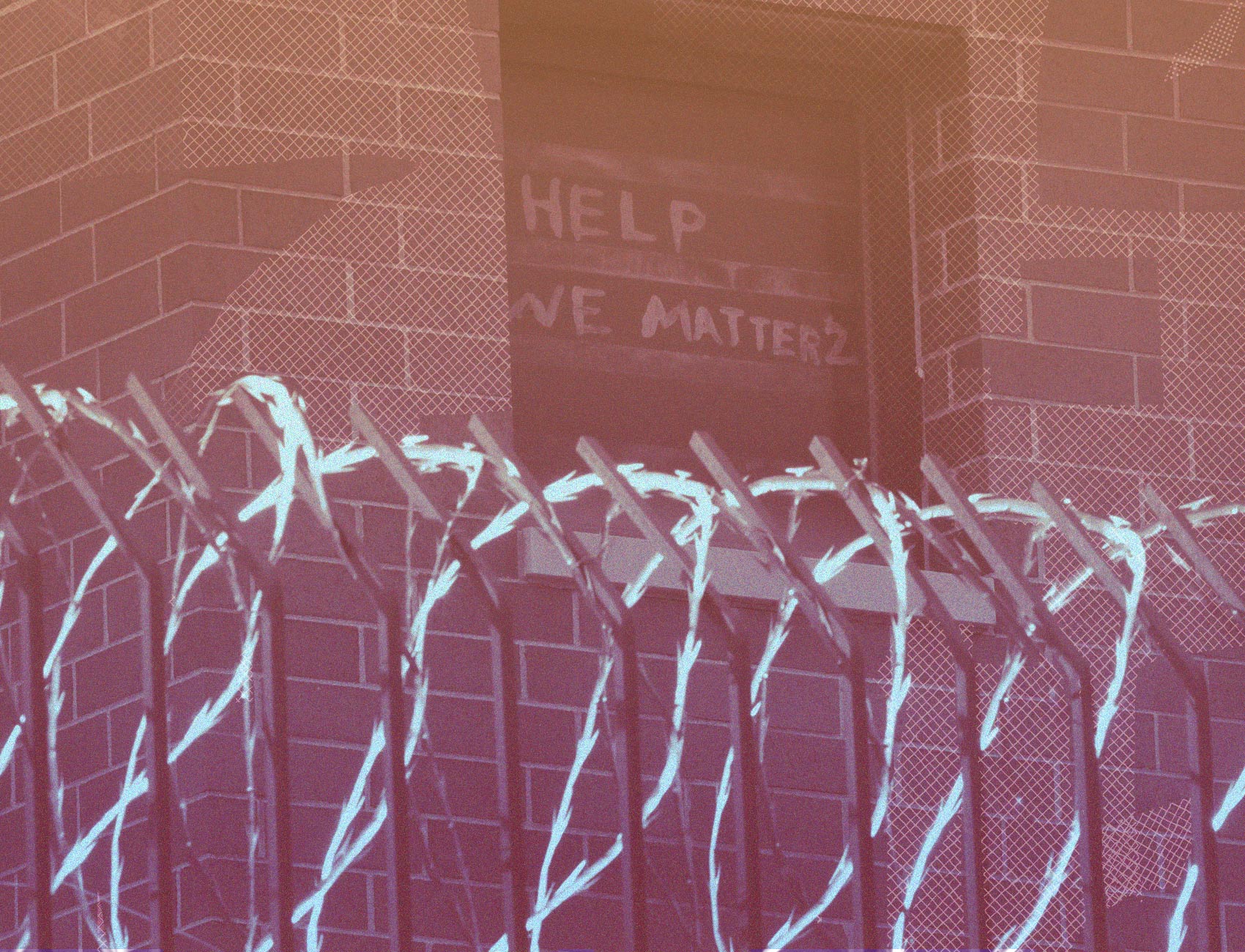

Some Federal Prisoners Are Getting Out As COVID-19 Spreads. Others Have No Chance.

Jeremy Hix is serving 70 months in federal prison for a sex offense—a conviction that disqualifies him for a Bureau of Prisons home confinement program, despite a health condition that puts him at risk of the coronavirus.

This Mother’s Day, Linda Craft was missing a very important person from her celebration—her son, Jeremy Hix.

Hix is currently serving a 70-month prison sentence at Federal Correctional Institution Loretto in Western Pennsylvania. He was sentenced in August for possession and distribution of child pornography after federal agents raided his home in Illinois roughly a year earlier and found he had used file-sharing software to download three videos of child pornography.

“This is his first time being incarcerated ever,” Craft told The Appeal. “[He’s] never ever been in jail one day in his life and then went from that to this overnight.”

Now, as COVID-19 moves through the federal prison system, Craft said she is concerned for her son’s health and safety. Despite having high blood pressure, a condition that can put someone at a higher risk of the disease, Hix does not qualify for release under a Bureau of Prisons home confinement program because of his conviction for a sex offense. Even if he qualified, he has not served enough of his sentence to be considered a priority for release.

The program, implemented at the direction of Attorney General William Barr, is supposed to prioritize release for incarcerated people who are most at risk of serious harm from COVID-19, who have served more than 50 percent of their sentence, or who have served more than 25 percent of their sentence and have 18 months or less to go. People convicted of violent crimes and sex offenses are excluded from the program.

“It makes no sense to limit a program that is designed to protect public health to an arbitrary category of ‘non-violent’ or ‘low-level,’” New York University law professor Rachel Barkow wrote in an email to The Appeal. “For starters, someone’s offense of conviction does not tell us anything about whether they pose a danger today.”

A 2012 report to Congress by the U.S. Sentencing Commission found that only about 7 percent of people convicted of possession or distribution of child pornography went on to be arrested or convicted of a new sex offense after being released from the BOP’s custody. The study followed more than 600 people convicted of possession or distribution, but not production, of child pornography who were sentenced in federal court during the 1999 and 2000 fiscal year.

On average, the people included in the study had been out of prison for more than eight years. Overall, 70 percent of people released after serving a sentence for possession or distribution of child pornography had no arrests whatsoever, and only about 2 percent were arrested or convicted of possession or distribution of child pornography again.

It makes no sense to limit a program that is designed to protect public health to an arbitrary category of ‘non-violent’ or ‘low-level.’

Rachel Barkow New York University law professor

“The [commission’s] own data indicate that this is a population with a very low rate of re-offense and can be successful in the community,” Guy Hamilton-Smith, a legal fellow for the Sex Offense Litigation and Policy Resource Center at the Mitchell Hamline School of Law, told The Appeal of those charged with federal sex offenses. “Pandemics are far less worried about what someone has done in the past than are our policymakers, and some more willingness to evaluate each individual’s circumstances would go a long way to ensuring the safety of our communities.”

A little more than 2,400 people have been released to home confinement under Barr’s directive so far. This equates to less than 2 percent of the total number of people in the BOP’s custody.

As of May 13, more than 4,100 people in federal prisons have tested positive for the disease and 50 incarcerated people have died. Seventy percent of the people who were tested for COVID-19 by the BOP have tested positive, as of May 1.

Barkow acknowledged that public officials are apprehensive about releasing people that the public may perceive as a safety risk. “All it takes is one case of someone who committed a crime who is released earlier than his/her initial sentence for the media or an opportunistic law enforcement official or politician to pounce,” she said.

But the focus shouldn’t be on potentially bad press, she cautioned. “We need to have lawmakers and officials committed to doing what’s best for public welfare, not what will make a tabloid or social media feed. Their job is to protect public health and safety, and in the face of this pandemic, that means releasing as many people as possible.”

In an April commentary for The Appeal, Shon Hopwood, a professor at Georgetown Law who was formerly incarcerated in federal prison, wrote that condemning people to possible death from COVID-19, just because of their sentence, “is inconsistent with the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment and with the important value that even those who have committed crimes, like me, deserve a second chance.”

To Craft, her 38-year-old son is a “quiet boy” who understood what he did was wrong and is trying to complete his prison sentence so he can “keep out of trouble and get home so he can make things better.”

“It’s waiting for that shoe to fall,” Craft said. “It’s only going to take one person to get it and it’s going to run rampant because there’s no way to stop it.”