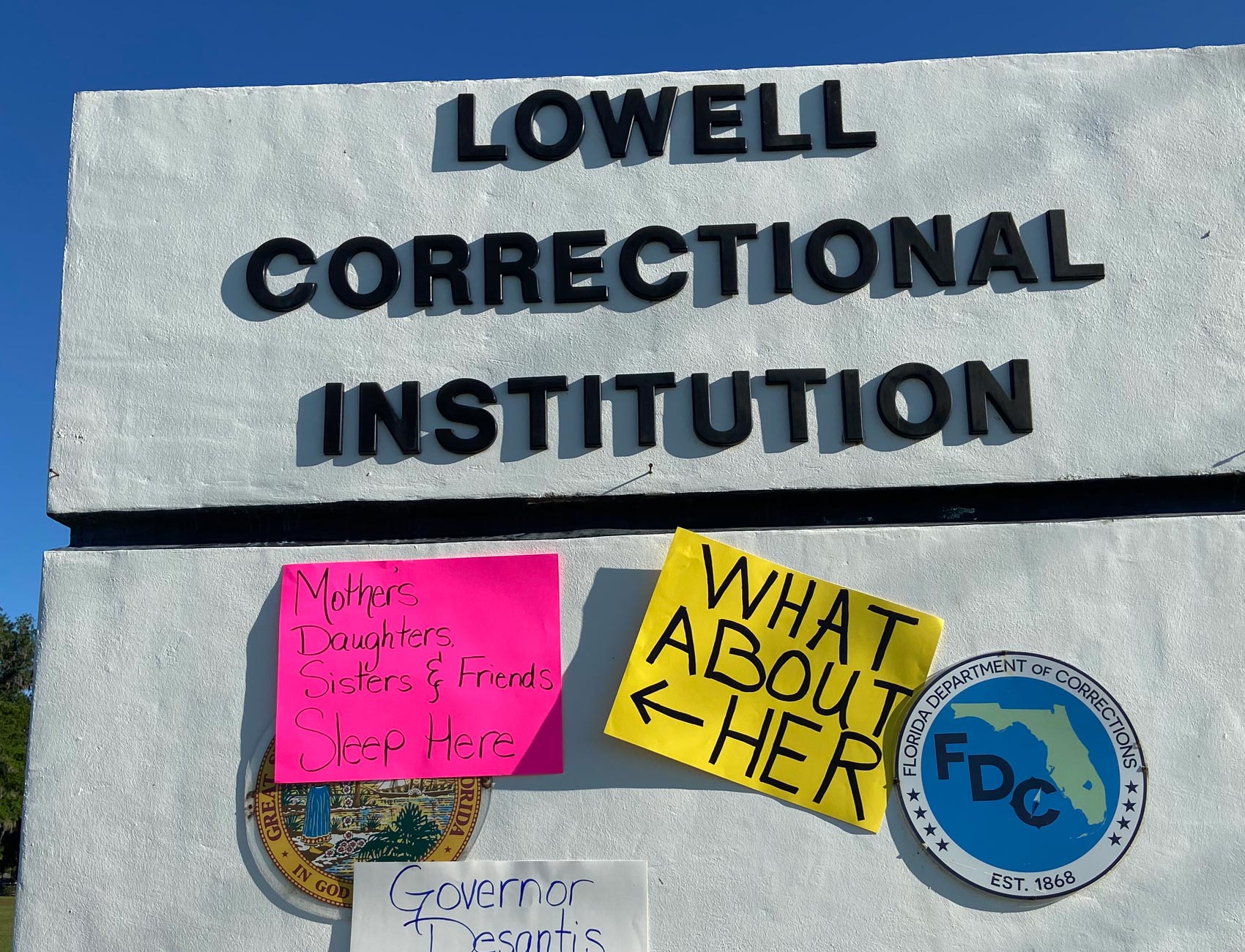

Fears Grow That Coronavirus Could Overtake Florida’s Largest Women’s Prison

With COVID-19 rapidly spreading across the state, there’s heightened concern that the conditions inside Lowell Correctional Institution, coupled with the prison’s sizable elderly and pregnant population, could foster a deadly outbreak.

Advocates and former prisoners across Florida are worried that the state’s largest women’s prison isn’t equipped for a potential outbreak of COVID-19, even as confirmed cases of the virus across the state continue to increase.

Although the Florida Department of Corrections has yet to confirm any COVID-19 cases at Lowell Correctional Institution, 28 cases have been reported in Marion County, where the facility is nestled among sprawling acres of thoroughbred horse farms. With infection rates across the state and country showing no sign of slowing, there’s a heightened fear that conditions inside Lowell—described by one lawmaker as “less than human”—coupled with its sizable elderly and pregnant population, is a perfect storm for a deadly outbreak.

“This is a circumstance where containing the virus is extremely difficult,” said Benjamin Stevenson, a staff attorney with the ACLU of Florida. Because attorney-client visits are still permitted and prison officials are required to report to work as usual, Stevenson said the issue is not only about the system protecting its incarcerated population, but also the surrounding community.

Florida’s state prisons have already taken preventive measures per Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations by suspending visitation and screening people for flulike symptoms before entering their facilities, according to a news release from the state Department of Corrections. The agency says it has “a plan in place” and staff members trained in the prevention and containment of infectious diseases.

But Representative Dianne Hart, a Tampa Democrat who has focused much of her work over the years on mending Florida’s criminal legal system, is skeptical. “I’m petrified that none of our facilities are really prepared correctly,” Hart said.

The state said it has suspended all nonessential prisoner transfers, but Hart fears it will only take one infected prisoner to be transferred to Lowell to spark an outbreak. She cites the prison’s lack of medical care as her main concern. Centurion, the private medical care provider used by Florida state prisons, is “one of the worst providers we could possibly have,” she said.

Centurion took over health services in the state’s prison system after the previous providers terminated their contracts in 2016 and 2017. Centurion was the only vendor to submit a bid for the contract. In a 2018 healthcare survey by the Correctional Medical Authority, the majority of women at Lowell’s Main Unit described the services as inadequate. At the time, physical surveyors noted several concerns, such as medical appointments not scheduled within the necessary time frame, medical orders being noted but not implemented and lack of timely follow-ups on abnormal lab results. In one record, surveyors found that a woman who had an abnormal mammogram result in September 2017 did not receive a breast biopsy until June 2018.

Centurion did not respond to emails or calls seeking comment.

Lowell, which houses roughly 2,600 women—474 who are over the age of 50—is just down the road from Marion Correctional Institution Work Camp and Florida Women’s Reception Center. On March 24, the state confirmed an employee at Marion tested positive for coronavirus. Three days later, FWRC confirmed an employee case.

The Florida Department of Corrections told The Appeal in an email that prisoners are being tested for COVID-19 and the county health department determines who is tested. However, the department couldn’t confirm if there’s a designated isolation room at each of its facilities or institutions.

The department was unable to provide the number of negative, positive, or pending tests run, stating that it oversees numerous facilities, prisoners, and employees, and “testing numbers are constantly changing.” The number of positive cases are “updated frequently” on the department website, it noted.

Lowell has dorms designated for prisoners who are elderly, pregnant, or have complex medical needs, the state Department of Corrections told The Appeal in an email. Today, the dorm for elderly women houses 87, while the medically intensive dorm houses approximately 22 women.

Gwynne Staples, who served a four-month sentence at the facility in 2016, arrived at Lowell when she was about five months pregnant. She was housed in the compound’s pregnancy dorm, which is designed to hold 70 women. “I can say that if my first time in prison was anything like my time at Lowell, I probably would have never went back,” Staples said.

Staples said she didn’t receive any prenatal exams while at Lowell. Despite writing multiple requests to the prison asking for prenatal vitamins, she was denied them until almost three months after she had arrived. She needed the vitamins, she said, given the lack of nutrition in the food at the prison. The majority of it was high-starch, which led her to gain almost 100 pounds.

Although Staples was full-term when she left Lowell, she and her baby were so malnourished that her obstetrician advised that she carry to 44 weeks—four weeks longer than a full-term pregnancy. Staples said she prays every night for the women who are still serving time there during this pandemic.

“It makes me emotional because I know that they’re suffering already,” she said. “It’s really terrifying to know what situation they’re already in and add this to it.”

Debra Bennett, a 52-year-old advocate and former Lowell prisoner, said she has sent the same letter to Governor Ron DeSantis’s office nearly a dozen times a day for the past week, pleading for the state to take larger strides in protecting its incarcerated population. In the letter, she wrote that “the pandemic will flourish in places like Lowell, with tragic results.”

Bennett requests that the state consider compassionate release of vulnerable women, such as those who are pregnant, housed in hospice, incarcerated with less than a year remaining in their sentences, or older than 60. She said this could not only reduce crowding in prisons and jails and a potential strain on medical facilities, but it could also save lives.

“These women are our neighbors, friends, part of our families, and we have a duty to do right by them,” Bennett’s letter reads. “This pandemic should remind us of the ways caring for the most vulnerable protects the entire community.”