FBI Crime Data for 2022 Is Out. Here’s What You Need to Know.

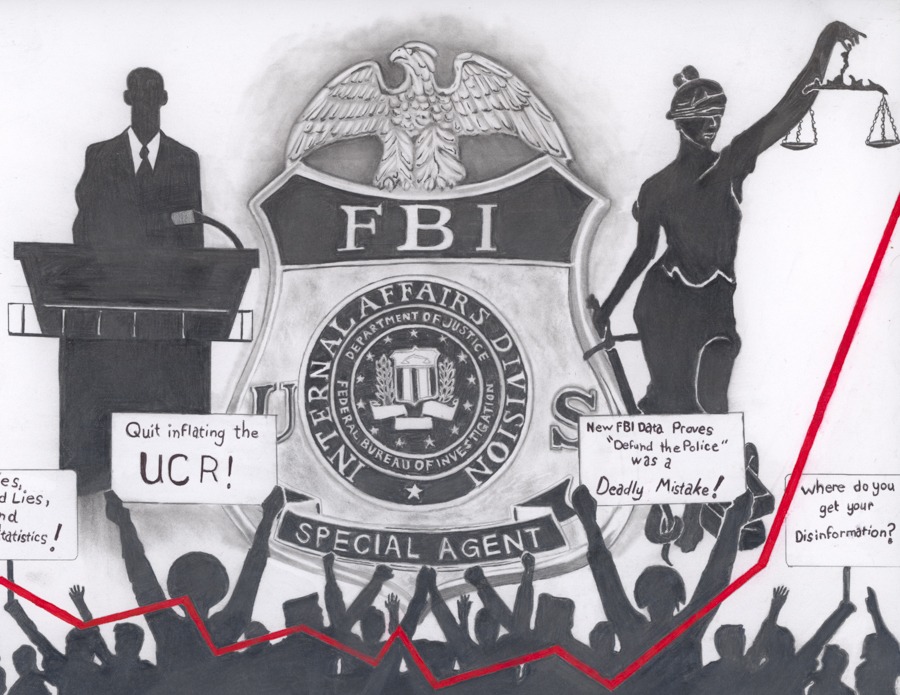

Lies, damned lies, and crime statistics.

This story was produced with support from The Academy for Justice at the Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law at Arizona State University.

On Monday, the FBI released its annual report on crime in the United States for 2022, just as it has done for more than 90 years.

The topline findings don’t make for especially exciting headlines. National crime rates remained more or less stable, barring a few minor fluctuations. Overall violent crime rates ticked down last year to pre-pandemic levels, even as homicide rates remained stubbornly high. Reported property crimes, which reached historic lows in 2021, increased slightly in 2022 but are still lower than any other year since the 1960s.

Nonetheless, if the past is any indicator, the new data will likely trigger a slew of media coverage, ranging from clickbait listicles about “the most dangerous cities in America,” to speculative think pieces conveniently blaming year-to-year fluctuations in crime on a single policy or idea. Already, we are seeing headlines seizing on the rise in property crime, without noting that the increase is from a modern record low.

As we prepare for the reactions to the new crime data, we must be aware of the limitations of the FBI statistics, and the ways they get manipulated for political purposes. The public’s perception of crime remains profoundly disconnected from actual crime rates, with the majority of Americans reporting that they believe crime has increased nearly every year between 1990 and 2022, according to Gallup opinion polling. In reality, violent crime fell during all but seven of those years, and property crime fell during all but three.

To make informed decisions about public safety, we must first establish a common understanding of what crime statistics say, and what they can and cannot tell us.

How Crime Becomes Crime Data

Because the vast majority of crimes never get reported to law enforcement, crime data is never a perfect reflection of crime itself. In order for a crime to end up in the FBI’s crime data:

- The crime must be reported to or observed by the police.

- Police must accurately record the crime in their internal database.

- The respective police department must share its data with the FBI.

Each step in the process presents its own challenges. Surveys conducted by the Bureau of Justice Statistics suggest that more than 50 percent of violent crimes and around 70 percent of property crimes are never reported to police. For certain types of offenses, such as sexual assault, upwards of 75 percent of incidents may never be officially documented.

Reporting rates can vary significantly from year to year, creating the appearance of trends that may not actually exist. For instance, research suggests that in the wake of the #MeToo movement in late 2017, the proportion of rapes reported to police increased by roughly 10 percent nationwide. Conversely, studies have found that high-profile incidents of police violence can make residents less likely to call 911 or report offenses to police. In some cases, much smaller changes can have a major impact on overall reporting rates. In San Francisco, for example, reported incidents of shoplifting doubled for one month in 2021 after one Target store implemented a new security system that automatically reported thefts to the police.

But even when crimes do get reported to police, it doesn’t mean they will ultimately submit accurate data to the FBI. The FBI only audits crime reports from local agencies when the agencies request it, which doesn’t happen often. Reporting by the Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel in 2012 found that fewer than 1 percent of law enforcement agencies received an audit during each of the preceding five years. Some states, such as Texas, perform their own checks to ensure accurate reporting, but many states do not.

This leaves ample opportunity for departments to report inaccurate numbers, often intentionally. Police have been manipulating crime data for as long as this data has existed. In 1931, just one year after the FBI began collecting crime statistics from local police, a presidential commission concluded that police departments could not be trusted to report accurate data, because they had skewed figures to seek “expanded powers and equipment for the agency in question rather than for the purposes which criminal statistics are designed to further.”

Since then, investigations by media outlets and oversight agencies have uncovered numerous examples of systematic efforts by police departments to manipulate crime data for their own purposes. Perhaps most notoriously, in 2009, the NYPD detained Officer Adrian Schoolcraft in forced psychiatric hospitalization for six days after he blew the whistle on efforts to artificially lower the crime rate by discouraging victims from reporting crimes and misclassifying serious crimes as minor offenses. Similarly, in 2014, an investigation by Chicago Magazine found that the Chicago Police Department had lowered the city’s official murder rate by recording homicides as non-criminal deaths.

Data manipulation can work in the opposite direction, too. A 2014 investigation by the Department of Justice found that a Georgia police department had reported roughly 11,000 aggravated assaults in 2009, even though the department had investigated fewer than 2,000. The over-reporting was ultimately uncovered as part of a bid to win a $3 million federal grant to hire more officers.

Of course, not every inaccurate statistic is the result of intentional dishonesty. In 2018, the Long Beach Police Department admitted that it had over-counted cases of aggravated assault because its crime analysts had misunderstood the FBI’s definition of the offense.

Inaccuracy issues aside, many police departments simply do not report any crime data to the FBI. For most of the past 20 years, somewhere between 15 to 30 percent of law enforcement agencies failed to report complete crime data to the FBI. As a result, we have no crime data for jurisdictions that cover somewhere between 5 and 10 percent of all U.S. residents.

Last year, the issue of non-reporting was worse than it had been in decades. That’s because the FBI stopped accepting data from agencies that use the Summary Reporting System (SRS), the method of compiling crime statistics that dates back to the earliest days of the annual crime statistics program. Instead, they required agencies to use the National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS), a more sophisticated approach to tabulating crime data that tracks an expanded list of offenses and includes more detailed information about each individual criminal incident, such as the property value of goods stolen in a theft.

Although NIBRS was launched in 1989, the FBI allowed departments to use either method to report crime data until 2021. Even though the FBI had announced its plans to phase out the SRS in 2015, many agencies—including the New York City Police Department and the Los Angeles Police Department—had yet to update their computer systems to comply with NIBRS reporting requirements. As a result, 2021 crime statistics included complete data from just over 50 percent of law enforcement agencies in the country. Nearly 40 percent didn’t submit any data at all.

As a consequence, the overall 2021 numbers the FBI released at the national, regional, and state levels were far less precise than usual, meaning it wasn’t possible to say for sure whether crime rose, fell, or stayed the same between 2020 and 2021.

In 2022, the FBI backtracked, allowing agencies that haven’t adopted NIBRS to continue using the old method to report crime data. The latest release includes data from 83 percent of all law enforcement agencies—responsible for policing more than 90 percent of the U.S. population—making it far more complete and reliable than last year’s data. However, it also makes it difficult to know how much of the change in the topline numbers is the result of actual changes in crime level versus changes in data-reporting practices.

What Crime Statistics Miss

Most of the crimes included in the annual crime report—homicide, aggravated assault, robbery, rape, arson, larceny, burglary, and motor vehicle theft—were selected by the International Association of Chiefs of Police in 1929, and they largely reflect concerns about street crime, rather than white-collar offenses and even organized crime.

These offenses aren’t even necessarily the most harmful from a societal perspective. Property crimes accounted for roughly $30 billion in economic losses in 2019; in contrast, a 2014 estimate by the Economic Policy Institute found that wage theft cost workers nearly $50 billion every year. Similarly, just under 19,000 people were killed in homicides in 2020, less than one-tenth of the number of people in the U.S. who die of pollution-related causes each year. Although most of those deaths are caused by perfectly legal means (operating a coal power plant isn’t illegal), criminal enforcement of environmental laws is virtually nonexistent.

The FBI’s limited definition of “crime” means that official statistics present only a partial picture of criminality. If someone robs a McDonald’s, the robbery might show up in the annual crime statistics. But if McDonald’s steals money out of its workers’ paychecks, the FBI’s crime figures won’t count it. In this way, the outsized focus on the most sensational types of crime allows some of the most egregious offenders to escape notice. This matters because many police departments use crime data to decide where to invest their resources. If the data placed an equal emphasis on white-collar crimes, police might struggle to justify their current enforcement priorities.

Although NIBRS includes an expanded list of offenses, it isn’t much better. Most of the new categories include things like drug crimes, illegal gambling, prostitution, and vandalism. The handful of white-collar offenses it does include, such as bribery and embezzlement, aren’t tracked by many law enforcement agencies, so these crimes are still unlikely to garner much attention.

How to Lie with Crime Statistics

Media outlets and politicians add to the public’s misunderstanding of crime by searching for simple takeaways in the numbers where none exist, in some cases leading them to abuse data that is already suspect to begin with.

By far the most common genre of crime data story, the “Most Dangerous Cities in America” listicle, is also the most erroneous. Writing an article that claims Philadelphia is more dangerous than Houston may be a good way to get clicks, but comparing crime figures across jurisdictions can elide important differences in geography, demographics, and how various municipalities are structured and governed. A city whose borders include affluent suburbs can’t be easily compared with one whose jurisdiction ends just a few blocks outside of an urban core.

Nonetheless, these comparisons are so frequent that the FBI now includes a “Caution Against Ranking” in its annual crime data release. The FBI notes that “rankings provide no insight into the numerous variables that mold crime in a particular state, county, city, town, tribal area, or region” and “lead to simplistic and/or incomplete analyses that often create misleading perceptions adversely affecting communities and their residents.”

Another major error media outlets make when reporting on crime statistics is aggregation. When an article talks about the “crime rate,” it’s lumping together each of the individual crimes that make up the FBI’s crime index. The problem is that this counts all crimes equally, regardless of severity. In 2019, there were just over 8 million index crimes reported in annual crime statistics. Of those, more than 5 million were cases of larceny/theft; just a little over 16,000 were homicides. The number of homicides could triple and the overall crime rate would barely budge.

Even when reporters use a slightly narrower measure, such as the violent crime rate, homicides still account for less than 2 percent of all offenses included in the FBI’s violent crime index. Thus, it’s important to be precise about which crimes are up and which are down.

Most importantly, crime statistics don’t tell you why crime rates are changing. Journalists will often turn to experts to try to fill in this gap, but even experts rarely know what causes crime to increase or decrease from year to year, or even decade to decade. Nonetheless, the hunt for simple explanations dominates much of the coverage around the annual crime data release: Crime is up because of bail reform, or because people bought more guns, or because schools were closed during the pandemic, or because kids are playing too many violent video games and listening to Beatles records in reverse. The reality is that all, some, or none of these factors might be at play, but identifying the impact of any single factor is often impossible.

What Are Crime Statistics Good for Anyway?

Given these issues, one might wonder if we shouldn’t just ignore crime statistics entirely. But this data can be helpful if used properly.

The FBI publishes historical crime data going all the way back to 1975, which can provide essential context for understanding how year-to-year changes in crime rates fit into longer trends. The increase in homicides that began in 2020 and continued into 2021 was one of the largest jumps in decades, but even so, homicides remained well below their peak in the 1980s and early 1990s. In 2022, they decreased by 6.3 percent, and preliminary data from the first half of 2023 suggests the downward trend will continue this year.

Additionally, the annual release of crime data includes more than just the topline figures that tend to dominate news coverage. The FBI also releases detailed statistics on topics like arrests, police employment, and use of force. While these data collections come with their own problems, digging deeper into FBI data can help reveal misallocations of police resources, such as departments that arrest thousands of people for low-level offenses while only solving a fraction of murder cases. This data can also expose racial disparities in law enforcement practices.

And, while distinct from the FBI’s annual reporting, many cities, including Chicago and Baltimore, publish detailed data on crimes and police activity in real time. This information can be useful for journalists, community organizers, and policymakers who want to hold law enforcement agencies accountable.

It’s impossible to have a meaningful debate about public safety policies and priorities without reliable facts and figures to ground discussion. Crime data can be a valuable tool in this context, but only to the extent that it’s accurate and the public is aware of its shortcomings. Until the FBI boosts participation in NIBRS—which may not happen until 2025 or later—media outlets and researchers have the responsibility to help fill in the gaps.