Exclusive: Immigrant Detainees In an Oregon Federal Prison Are Being Held In General Population Units

As a consequence, authorities are keeping them in cells for 22 to 23 hours a day, according to Oregon’s federal public defender.

Reuters reported this month that federal authorities were moving 1,600 immigrant detainees, awaiting civil immigration court hearings, to five federal prison complexes across the country, a practice that has never been carried out on such a large scale. The Appeal has learned that immigrant detainees are being held in prison housing units with the general population in at least one of these federal prisons, in Sheridan, Oregon, rather than in separate facilities. The detainees at FCI Sheridan have been there since mid-May.

The arrangement could be dangerous and raises constitutional concerns, according to a source in the federal Bureau of Prisons and Lisa Hay, Oregon’s federal public defender.

Prison staff members are concerned about detainees’ safety during their stay in the facility, said the Bureau of Prisons employee, who requested anonymity because they were not authorized to speak about the issue. Consequently, prison officials have sought to cut off these 123 detainees’ interactions with the general population, confining them to their cells for 22 hours a day this week, according to Hay. During brief respites outside their cells, detainees are allowed to shower and attempt to use the phone, said Hay, who has visited the facility with her staff three times over the last two weeks.

Carissa Cutrell, an ICE spokesperson, confirmed this physical arrangement in an email, noting that there are “ICE detainees and federal inmates in the same unit, but on different tiers.” Asked about the claims of 22 hour confinement Cutrell said that is not “ICE’s understanding” and said the detainees are supposed to be moved to their own housing unit Friday. Cutrell did not respond to The Appeal’s inquiries as to whether ICE detainees at other federal prisons have been held in the same housing units as federal inmates.

The facility’s long-term federal inmates have access to educational and recreational programs as well as library and computer resources. But prison staff members have not made any decisions about what, if any, activities immigrant detainees will have access to while authorities try to find facilities for them outside the federal prison system, according to the BOP source.

When ICE transfers detainees to a separate unit, these restrictive conditions will change, Cutrell says. “Since there were ICE detainees and federal inmates in the same unit, but on different tiers, they had to split recreation time,” said Cutrell.

The confinement of detainees in federal prisons across the country is expected to last for at least three more months.

Lawmakers who visited the Oregon prison last weekend denounced the restrictive-hour rules in a June 16 press conference. But no previous reports have revealed why immigrants are being subjected to these extreme confinement conditions. They appear to be a direct consequence of federal authorities’ attempts to isolate detainees from the general population, after allegedly placing them directly in the general population units.

Asked about the decision to confine the detainees for so many hours in these units, the BOP source said, “I think it was a last minute safety precaution. There wasn’t a lot of notice to institutions that they’d be taking detainees so I highly doubt anyone knew right from the start that they’d be confining them for so long.”

Immigration detainees have been in BOP facilities in the past, says Donald Kerwin, executive director of the Center for Migration Studies, but he has never heard of a situation like the one apparently at hand. “It’s true they have housed a minority of immigrant detainees over the years,” said Kerwin in a phone interview, pointing to facilities like FCI Oakdale in Louisiana. “But the idea of commingling them with people who are serving sentences, that’s a practice that has totally been renounced under prior administrations.”

Dora Schriro, founding director of ICE’s Office of Detention Policy and Planning, said she could not recall an instance in which civil immigrant detainees were housed in the same units as federal inmates.

“The vast majority of civil detainees do not have criminal histories and holding two different populations, one with some depth of prior criminal history, with one that has little to no criminal history, is ultimately going to create some very challenging situations,” Schriro said in a phone call, pointing to the language barriers and lack of legal services federal prison could offer immigrants.

In the past, many immigrants being held in detention during their deportation proceedings were eligible for bond hearings, which gave them the opportunity to remain outside detention while their immigration status was decided. A Supreme Court decision in February held that certain immigrants are not eligible for bond, leaving more of them in detention for longer periods of time. The litigation is ongoing.

Reached by phone, Amber Lee Newmann, a spokesperson at FCI Sheridan declined to answer The Appeal’s inquiries, directing all questions to the Bureau of Prisons central office. The central office also declined to answer requests, referring questions to ICE.

Oregon’s Office of the Federal Public Defender is investigating whether the punitive nature of the confinement violates the Constitution for this population of asylum seekers, who do not stand accused of any crimes.

“These are not people being held for crimes,” Hay said. “These are people being held for asylum.”

Cutrell declined to provide information on whether the 123 detainees are all asylum-seekers.

According to The Oregonian, of the 123 people currently in Sheridan, 52 listed India as their home country. Several of these detainees said they were Sikhs or Christians fleeing religious persecution. Others are from Nepal, Peru, Russia, Honduras, Guatemala, Armenia, China, and Brazil, according to the Statesman Journal.

In addition to the restrictive living conditions, detainees at Sheridan as well as another federal prison in Victorville, California, have been denied access to immigration attorneys, according to local media reports. Consequently, what little is known about detainees’ living conditions has largely come from concerned public officials and criminal defense attorneys, like employees from Oregon’s Office of the Federal Public Defender, who have managed to make it inside.

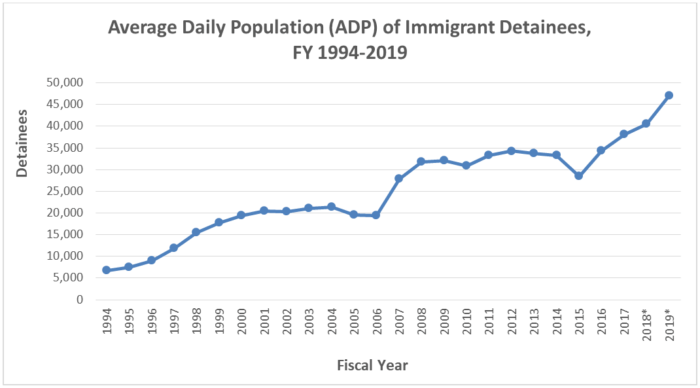

“They haven’t been able to see immigration lawyers,” said Hay, referring to the detainees at Sheridan. “We’ve been able to see them but we’re not immigration lawyers, so we’re assessing the constitutionality of their confinement.”The transfer of detainees to federal prisons signals the incredible stress the immigration detention system is currently handling. Cutrell, the ICE spokesperson, told the Associated Press this week that capacity at immigration detention centers, where those not facing criminal charges are often held, has been exhausted by the Trump administration’s zero-tolerance policy.

The new policy has also increased the amount of criminal prosecutions for misdemeanor illegal entry by 60 percent between January and April along the southwest border.

These arrests have flooded federal jails and prisons, and county jails as well, leaving authorities scrambling to find places to house detainees. As federal jails have filled, the U.S. Marshals have placed detainees in private prison facilities also used by ICE. As ICE facilities have reached capacity, the U.S. Marshals have sent those in federal custody to far-flung county jails in California and Arizona.

On Monday night, the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California filed an emergency lawsuit in the Central District of California to put an immediate end to the denial of attorney access to the detainees housed in the Victorville prison, which is holding up to 1,000 civil immigration detainees. An ACLU spokesperson told The Appeal that they have no idea what the conditions are like for immigrant detainees inside the Victorville prison, because no lawyers have been allowed access.

The BOP employee argued that detainees’ lack of access to immigration lawyers is not “due to nefarious reasons.” “It takes a while for new inmate to get their visitor list approved,” the employee said. “From what I heard on the news, most of the detainees don’t have lawyers. If you don’t already have a name to put down on your visiting list it’s going to likely delay the process.”

But Cutrell of ICE laid the blame for the lack of access to lawyers on protestors camped outside ICE offices in Portland. “The detainees at Sheridan were scheduled to attend legal presentations with local immigration attorneys at the Portland ICE office on June 20, 21, and 22,” Cutrell told The Appeal. “However, those presentations were canceled because the ICE building was inaccessible due to ongoing protests. ICE is in the process of rescheduling those presentations.”

The federal prisons were given little time to prepare for the new arrivals. Union representatives for the Victorville workers wrote a blog post shortly after the announcement of the transfer of civil immigration detainees to the federal prison, claiming that the prison was “not ready to accept this influx of inmates with the current staffing levels,” after a recent hiring freeze. On Tuesday, LAist reported that the BOP had confirmed a case of chickenpox among the immigrant population it is detaining, a medical situation that staff had brought up during a picket of the prison last Friday.

At least six of the 123 would-be asylum seekers at Sheridan are fathers who were separated from their children at the border, Senator Jeff Merkley of Oregon told the Willamette Week earlier this week. On Wednesday, Trump issued an executive order saying that the federal government will now be keeping families together throughout their criminal and immigration proceedings. It is unclear whether this order means parents in deportation proceedings, like those being held in federal prison in Oregon and California, will be reunited with their children elsewhere. (Under U.S. law, children cannot be held in federal prisons.) The Bureau of Prisons declined to address The Appeal’s questions about what would happen to detainees in federal prisons who have been separated from their children. ICE said it would respond to the questions “at a later time.”

Immigration experts have pointed out that Trump’s executive order has loopholes that allow the government to continue to separate parents and relatives from children, and sets up a showdown in the courts that could strike down the executive order.

But ICE has fewer options over where to place immigrant detainees than in years past. In 2017 California passed new “sanctuary” laws that bar counties from adding new contracts for ICE detention or expanding old ones—sealing off a large swath of the southern border from immigrant detention purposes. As a result, federal prisons are one of the only remaining alternatives. With the recent implementation of zero-tolerance policies, the immigration system’s substantial backlog has only grown, and the Department of Homeland Security has become desperate to add capacity. Last year, the agency began soliciting proposals for at least five new ICE detention centers across the country. The new executive order also instructs other federal agencies—including BOP and the Pentagon—to make facilities available for immigrant detention purposes.

Activists say the shift of immigrant detainees seeking asylum into federal prison speaks to the criminalization of migration more broadly. “If we’re asking where are the children, we also have to ask where are the parents?” Jacinta Gonzalez, a field director at the immigrants’ rights group, Mijente, said in a phone interview. “We have to understand this as an escalation of previous policies that go across both sides of the aisle, so we must demand the recall of the racist laws that put people in cages to begin with.”