Epstein’s Death Reveals ‘Culture of Indifference’ in Jails

The same culture exists across the country, experts say—with devastating effects.

Jeffrey Epstein’s apparent suicide has drawn headlines since it happened. But advocates say the only unusual aspect of his death is how much attention it’s receiving. The circumstances are painfully familiar to prisoners, their families, and advocates.

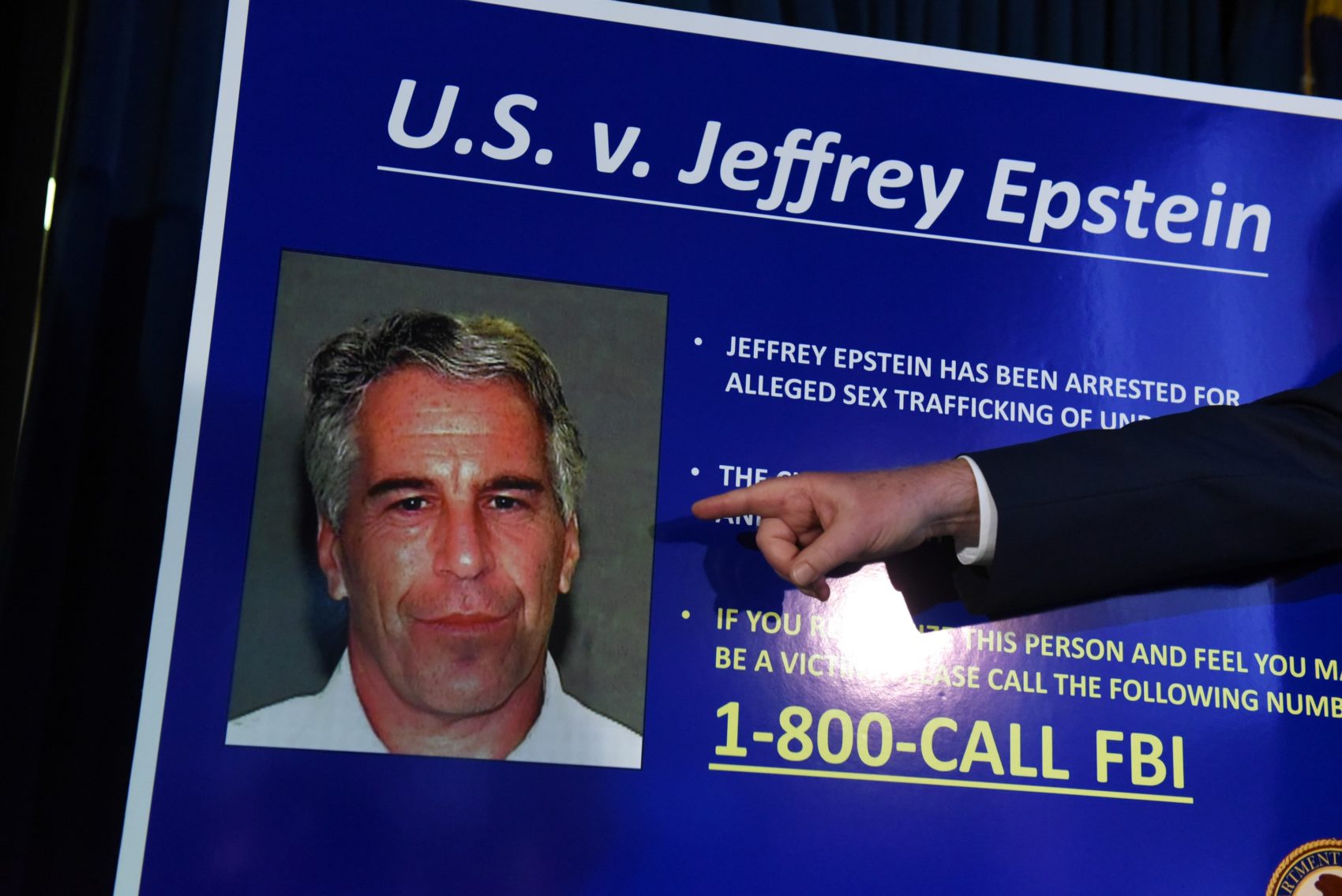

On Saturday, Epstein was discovered dead in his cell at the federally run Metropolitan Correctional Center in New York. The billionaire was facing charges of sex trafficking, and accused of targeting underage girls.

“He is obviously an unusually unsympathetic character, but when the government takes you into custody, the government assumes a duty to protect you, including to protect you from self-harm and suicide,” said David Fathi, director of the ACLU National Prison Project. “And it’s a duty that all too often the government completely fails to discharge.”

Suicides in jail are indicative of a broader “culture of indifference” in jails that can have fatal results, according to Fathi.

Prisoners at the Metropolitan Correctional Center, where Epstein was housed, have allegedly been subjected to beatings by staff, rodent-infested cells, and solitary confinement, according to prisoners, lawsuits, and human rights groups.

“This is a population where, when it comes to everything, whether it’s their medical needs or mental health needs, whether it’s protecting them from rape and other kind of assault, it’s just not seen as a high priority,” said Fathi. “Many people unfortunately seem to think whatever happens to you behind bars, even if you’re a pretrial detainee presumed innocent, that’s what you deserve.”

That indifference has shown itself across the country. In Oregon, Madaline Pitkin, 26, died while detoxing in a Washington County jail. In the week before her death, she pleaded for help, but was largely ignored. The correctional healthcare company Corizon settled a lawsuit in December filed by Madaline Pitkin’s family.

In DeKalb County, Georgia, a detainee was recently photographed holding a sign that read, “We sleep and breathe mold.” And on Rikers Island in New York, detainees were without air conditioning in July when temperatures reached nearly 100 degrees.

Incarceration itself is a traumatic experience, said Michele Deitch, a University of Texas at Austin lecturer who specializes in prison and jail conditions. “They no longer have freedom,” said Deitch. “They don’t have access to their home or their cars or their job or their family. They don’t have access to their medication, their clothes. Everything about their life as they knew it comes to an abrupt halt and they have to adjust to this new world.”

Jail can be particularly cruel for people with mental health needs, and suicides often occur early in a person’s incarceration. In May, Nicholas Colbert, an Army National Guard veteran, was found hanging in his cell in a Cleveland jail three days after his arrest for drug possession. His was the fifth suicide in the jail system over the past year.

In April, the Southern Center for Human Rights sued Sheriff Theodore Jackson of Fulton County, Georgia, and several jail employees over their practice of placing women who are mentally ill in solitary confinement. According to the suit, mental health treatment has amounted to a few questions yelled through a cell door. In July, U.S. District Judge William Ray II ordered a preliminary injunction, requiring the sheriff to address the unconstitutional conditions at the jail.

“To see how we treat people with serious mental illness in a jail setting, it’s just so wretched it almost takes your breath away,” said Sarah Geraghty, managing attorney for impact litigation at the Southern Center for Human Rights.

Jail deaths are preventable, advocates say, but that requires a shift in thinking about people behind bars. All people entering jails should be screened by trained medical and mental health staff, not corrections officers, receive effective treatment, and be placed in appropriate housing, according to advocates.

“None of this is complicated,” said Fathi. “It’s not something we don’t know how to do.”