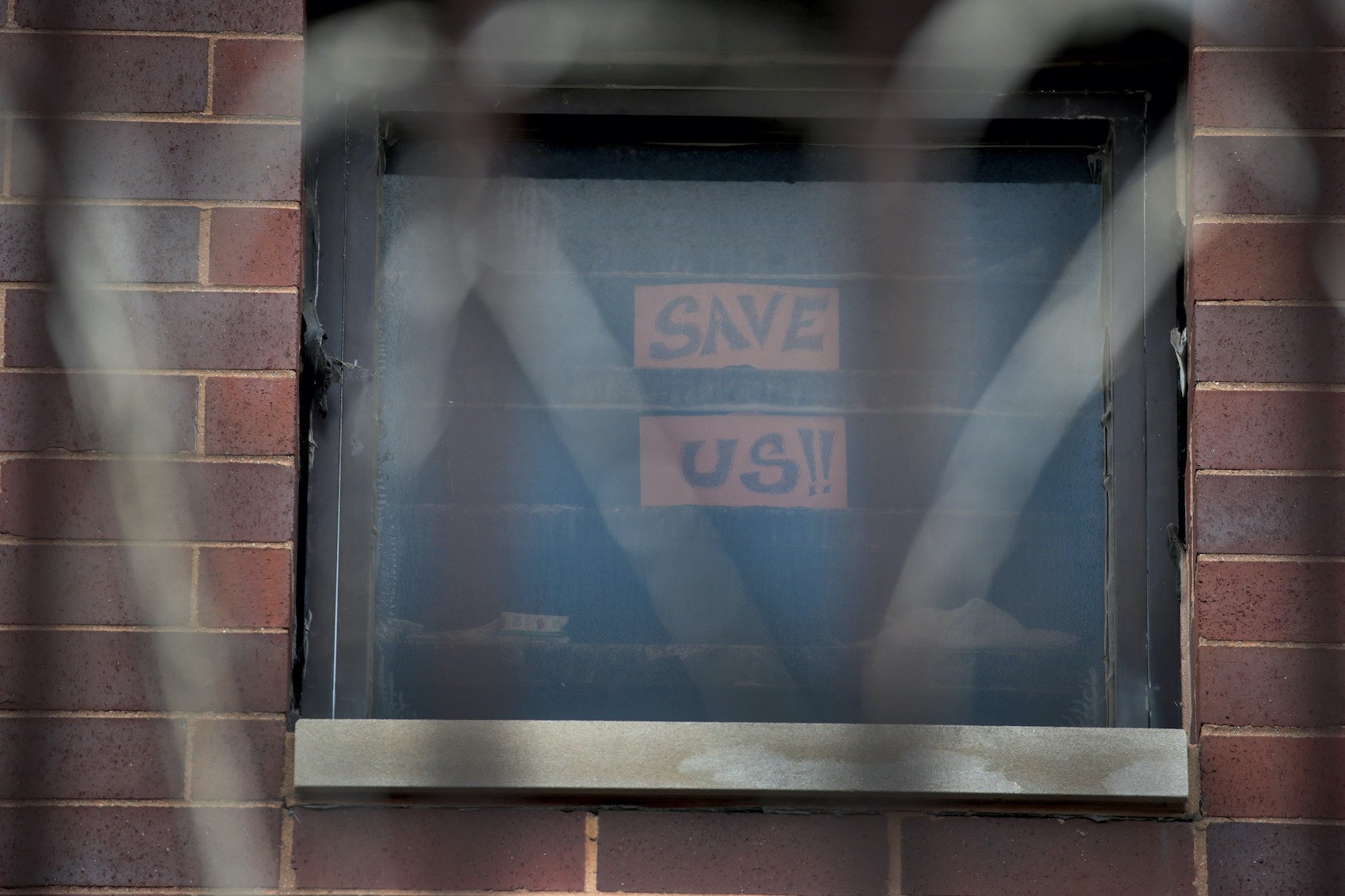

Dozens Of Reports From Inside Cook County Jail Paint A Grim Picture As COVID-19 Cases Soar

Prisoners say the jail, which has seen more than 800 confirmed cases, is a ‘death trap’ plagued by sanitary issues and a lack of testing. Their testimonies stand at stark odds with the sheriff’s office, which says it is keeping ‘staff and detainees as safe as possible.’

The Cook County Jail in Chicago, America’s largest single-site pretrial detention facility, is now one of the top coronavirus hot spots in the nation. Despite an April 9 order from a federal judge requiring Sheriff Tom Dart to provide COVID-19 testing for symptomatic prisoners, implement social distancing, and distribute adequate sanitation and personal hygienic supplies, more than two dozen detainees interviewed by attorneys, advocates, and reporters in the last two weeks describe living conditions conducive to the spread of the virus and a lack of access to testing. On Monday, U.S. District Judge Matthew Kennelly issued a preliminary injunction ordering the sheriff to do more. To date, the sheriff’s office has reported more than 800 confirmed cases of the virus, more than half of them among prisoners. So far, six prisoners and one guard have died of COVID-19.

This crisis has generated an unprecedented amount of prisoner testimonials about jail conditions. Their narratives are remarkably similar to one another and at stark odds with many of the sheriff’s claims. For what seems like the first time in Dart’s 13-year tenure, complaining voices of the people in his custody outweigh his professional public relations operation. Some criminal justice reform advocates are also finding a grim upshot to the coronavirus outbreak at the jail: It is proving that a drastic reduction of pretrial detention is achievable.

The criminal justice apparatus in Cook County lumbered to prepare for the inevitable arrival of the virus at the jail. On the eve of the statewide lockdown on March 21, the Cook County public defender’s office filed an emergency motion, with support from public health experts and 25 advocacy groups, demanding the release of all medically vulnerable detainees from the jail. This didn’t happen but judges did begin expediting some bail review hearings and an increasing number of defendants were put on house arrest. The state’s attorney’s office, meanwhile, stopped prosecuting low-level crimes, such as drug possession. In recent weeks the population of the jail—a 96-acre facility designed to hold more than 10,000 prisoners—has dropped by more than 1,300 people to a low of less than 4,200. But it was not enough to prevent the outbreak.

The first case of COVID-19 among prisoners was confirmed on March 23. A week later, 134 detainees were sick. On March 27, Dart held a press conference touting ”single-celling” for almost all prisoners and saying reports of lack of access to soap were “lies.” Meanwhile, the head of the jail’s medical division (which is under the purview of Cook County’s Health and Hospitals System and not the sheriff’s office), Dr. Connie Mennella, said the division was “testing every person who is symptomatic,” but the severity of the outbreak grew precipitously. That same day the union representing healthcare workers at the jail called for a “drastic” reduction of the jail population.

On April 3, a federal class action lawsuit was filed against Dart over jail conditions and by the end of the second week of April, some prisoners went on a hunger strike demanding access to soap and other sanitation supplies.

“The beds are three feet apart, the phones are two feet apart and then the seats at the table are a foot apart, so there is no social distancing,” said Jafeth Ramos, 23, who has been held at the jail without bond on murder charges since 2016 and is housed in a dorm-style tier with 25 other women. “I feel like it’s a death trap in here because we don’t have no fresh air from outside … the air we breathe is recycled air from the vents so the coronavirus is in the air.”

Sheila Rivera, a correctional officer who died on April 19, was a guard on Ramos’s tier. Ramos said that although her unit is now on “quarantine,” with all prisoners’ temperatures being checked twice a day, it’s impossible to get a COVID-19 test for any symptoms other than fever. She added that prisoners receive a mask every three days and two hotel-size soap bars each week, but that their bed linens haven’t been washed since the start of the outbreak. In a statement, a spokesperson for the sheriff said new masks are issued to detainees every day and “laundry continues to be done daily.”

Ramos said prisoners have access to hand sanitizer on the wall of the dorm, but the cleaning supplies are watered down, and it’s impossible to maintain proper hygiene with shared showers, toilets, and phones. Ramos believes she has contracted the virus already, as do many of the other women in her dorm. “I had the hard breathing, the cough, the stopped-up nose, I couldn’t taste or smell and I had a headache, but I never had the fever,” she said. “If you don’t have a fever they don’t test you.”

Affidavits from 13 prisoners filed in the federal lawsuit describe similar conditions in men’s divisions of the jail: units where people are still held in dorms or two to a cell; no proper social distancing or cleaning of shared showers, toilets, and tables; a lack of access to testing, even for those who had acute symptoms or had contacts with others who tested positive. Prisoners have reported a total shutdown in non-COVID-related medical services: diabetics can’t get blood sugar checked, chemotherapy appointments have been canceled, other requests for medical care go unanswered. South Side Weekly’s recent publication of six interviews with people in the jail’s Residential Treatment Unit offered a similar picture.

A spokesperson for the sheriff denied the cessation of medical services. “These affidavits have not been corroborated by any underlying evidence or documentation,” he wrote in an email to The Appeal. “Detainees continue to receive their medication on schedule and medical requests continue to be processed.” He added that questions about medical services at the jail should be directed to the county health and hospitals system; its representatives didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment.

Advocates behind the federal suit are concerned that the official response to the pandemic endangers pretrial detainees’ health and violates their constitutional rights. “The [Illinois] Supreme Court has put in place a system that takes pressure off of judges to hold trials and resolve cases but provided no corresponding guidance on how to handle the rights of people who remain incarcerated during the suspension,” said attorney Sharlyn Grace, executive director of the Chicago Community Bond Fund, one of the groups that brought the suit on behalf of jail detainees and collected testimonials from more than 500 of them since the start of the pandemic. “This is a recipe for indefinite detention.”

Brandon Perkins, 27, has been at the jail without bond since 2016 on a felony murder charge. He’s discouraged about delays in non-emergency case processing due to the statewide lockdown. “If we can’t get to court we can’t move on from this place,” he said. “It’s worse to be here than in prison because there’s so much uncertainty.”

Perkins is held in a single cell at Division 11 and was one of the organizers of the hunger strike over lack of access to proper sanitation, delays in case processing, and visitation cancellation. He said conditions inside the jail have improved somewhat since the strike. Supervisors had come to speak with prisoners, and everyone on his tier now gets a mask per day and access to hand sanitizer; visits are slowly being coordinated through Skype. Still, he said he has been unable to see a doctor about a shoulder injury and get a prescription refilled.

Ioan Lela, also in Division 11, was mid-trial for 2016 murder and home invasion charges when the pandemic lockdown began. He said he had COVID-like symptoms for two weeks but wasn’t able to get a test. He’s representing himself in court and said the pandemic has made it even harder for a pro se defendant like him to have a fair hearing.

“I did my opening argument and cross examination of the first witness on February 26 and I was supposed to go back to trial April 14, but of course that didn’t happen,” Lela, 38, said.

Prisoners that The Appeal interviewed all said they felt like their lives don’t matter. “I guess because they think we’re criminals and we’re supposed to be here,” Ramos said.

Perkins said it seemed like some community sympathy was building, with a caravan of supporters mobilizing outside the facility on April 7 and nurses staging a protest on April 10, but then, on April 14, Dart’s office released video of an attack on correctional officers by people held in Division 9. The video clearly showed people housed two to a cell; it’s not clear whether the attack was related to the COVID-19 outbreak.

“They kinda messed it up for us, the people who did the attack,” Perkins said. “We kinda had some momentum going. Tom Dart was saying they’re trying not to release any violent offenders and I feel like it adds to the stigma.”

Lela said the release of the video seemed to be a calculated public relations move on Dart’s part as the sheriff was facing increased criticism for his handling of the virus outbreak. “Tom Dart is quick to release a video when it benefits them.”

In an emailed statement, a spokesperson for Dart denied or challenged the claims made by the detainees that The Appeal and others interviewed. “The Sheriff’s Office continues to work with all federal, state, and local partners to ensure we have appropriate supply of all materials necessary to keep our staff and detainees as safe as possible,” he wrote. “The information provided to you is both false and uncorroborated by any evidence or documentation.”

According to Judge Kennelly’s preliminary injunction, Dart has until Friday to further improve sanitation, increase testing, reduce dorm-style housing and all but eliminate double-celling. But with the infection rate at the jail almost 20 times higher than in Cook County as a whole, it’s likely that more prisoners and guards will get sick and may die in the days and weeks to come.

Although the rapid spread of the virus at the jail has tarnished Dart’s reputation and exacerbated a public health emergency in Chicago, it has also shown that mass decarceration of people accused of crimes is within reach if the political will is there.

“People are understanding through the conversation about COVID-19 in jails and prisons how dangerous jails are,” said Grace, whose organization has been on the front lines of fighting to abolish money bail in Illinois and managed to bail out 20 people from Cook County in the last few weeks. “Jails have always been unhealthy, unsanitary places where people don’t receive the care they need. They’ve always had a high rate of mortality. People are hopefully coming to understand that through this acute crisis, and that could be a lesson we take forward to reduce the use of pretrial jailing.”