The Voices Warning Trump About COVID-19 In Prisons Are Growing Louder. Will He Listen?

There are no good reasons for the president to keep vulnerable people behind bars any longer.

This commentary is part of The Appeal’s collection of opinion and analysis.

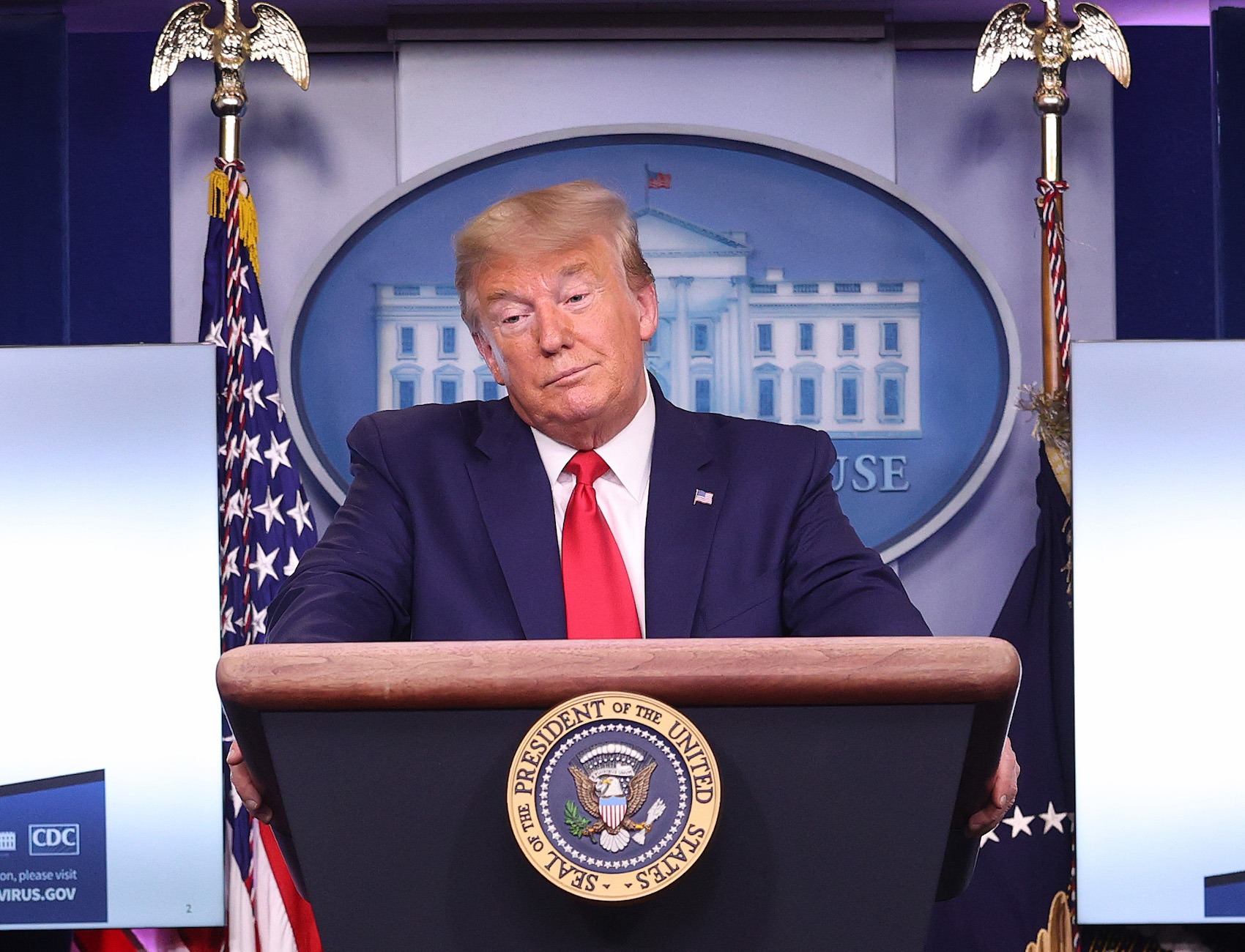

In the weeks before the United States became the global leader in confirmed cases of COVID-19, President Donald Trump repeatedly squandered opportunities to demonstrate basic competence, much less principled leadership. At first, he confidently predicted it would “disappear,” and dismissed criticisms of botched containment efforts as the Democratic Party’s “new hoax.” On March 16, as the stock market plummeted and he advised against attending gatherings or going out in public, he awarded his administration’s response to the crisis a perfect 10 out of 10 rating.

This past Sunday—the same day his home state of New York officially surpassed 1,000 deaths—he took to Twitter to discuss the TV ratings of his press conferences.

There remains, however, a significant, substantive step the president could take to slow the virus’s spread—one that would not mire him further in controversy of his own creation. It involves exercising authority the Constitution entrusts only to him, and, incredibly, it would earn the immediate praise of staunch allies and dependable critics alike: Donald Trump should use his executive clemency powers to release from federal custody as many incarcerated people as possible, as quickly as he can.

Even in the hyperpartisan, hyperpolarized world in which we live, the lifesaving potential of this move is not seriously in dispute. Last week, more than 400 former judges, prosecutors, and Department of Justice lawyers signed an open letter urging President Trump to reduce the populations of federal detention and correctional centers. They recommended focusing on commuting the sentences of people who are older or more vulnerable to COVID-19, as well as those who have served most of their sentences, in order to limit the crowding that will exacerbate outbreaks behind bars. The signatories used to be responsible for putting people into prison; now, in the face of a pandemic, they are united in their efforts to get people out.

Doing so, the authors argued, would set a powerful example for governors and sheriffs considering similar steps in state prisons and local jails, where the vast majority of incarcerated people are locked up. “The actions you take today will mitigate harm and devastation for millions of people across this country, ensure that America is acting in the best interest of all of us, and will ultimately save lives,” they wrote. “There is not a moment to lose.”

In a March 27 letter to the White House, a group of public health experts—people with no professional interest in either promoting mass incarceration or ending it—repeated these same warnings. “The conditions in federal prisons and immigration detention centers present significant health risks to the people housed in them, the correctional officers, health care professionals, and others who work in them, and to the community as a whole,” they said. In an opinion piece published by The Appeal, North Dakota Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation director Leann Bertsch—hardly an official one might expect to bless mass releases of people in custody—partnered with medical professor Brie Williams to state in unambiguous terms the plight faced by agencies like hers.

“Correctional facilities are simply not equipped to handle a pandemic,” they wrote. “Decisive action by governors and the President now can save lives. … Business as usual will not.”

In Washington, D.C., too, a legislature that famously cannot agree on anything is suddenly finding common ground. On March 23, a bipartisan group of senators asked Attorney General William Barr and Federal Bureau of Prisons Director Michael Carvajal to exercise their powers to transfer elderly, terminally ill, and lower-risk incarcerated people to home confinement. It also notes the Bureau of Prison’s recent opposition to the “vast majority” of compassionate release petitions, and begged the agency to include vulnerability to COVID-19 among the “extraordinary and compelling” circumstances that merit release.

Perhaps most significantly for a president preoccupied with winning four more years in the White House, polling conducted by Data for Progress shows that protecting incarcerated people from COVID-19 is not a partisan issue. (The report was co-produced by The Justice Collaborative Institute, which is, like The Appeal, an independent project of The Justice Collaborative.) Two-thirds of likely voters, including 59 percent of self-identified “very conservative” voters, want elected officials to reduce jail and prison overcrowding. Sixty-three percent support reducing jail admissions by having police use summonses or tickets instead, and 52 percent say they’d back releasing anyone charged with an offense that does not pose “a serious physical safety risk to the community.” A March 24 letter calling for more commutations of federal sentences was signed by both left-leaning organizations like the Justice Roundtable and conservative stalwarts like the R Street Institute and FreedomWorks.

Before managing a pandemic became the most pressing duty of government, the Trump administration took more than a passing interest in criminal justice issues. The First Step Act, a prison reform bill passed by overwhelming House and Senate majorities in late 2018, expanded compassionate release and allowed for the reduction of harsh sentences handed out during the peak of the failed War on Drugs. Critics persuasively argued that the bill did not go nearly far enough. Still, for a self-styled tough-on-crime politician who ran for office vowing to “liberate” America from the “lawlessness that threatens their communities,” this willingness to acknowledge and address the legal system’s shortcomings came as a pleasant surprise.

There is also evidence that Trump understands the appeal of pitching himself as a champion of fairness. A Super Bowl ad that served as the de facto launch of his re-election bid focused not on wall-building or trade-war-waging, but instead on the First Step Act’s passage and his use of executive clemency. As NYU law professor Rachel Barkow noted at the time, the choice to lean into this aspect of the president’s record shows, if nothing else, that “criminal justice reform can be a winning issue for anyone.” Releasing vulnerable people from federal custody could be a savvy move at a moment when he desperately needs to make one.

Even after a month of closed businesses, cancelled events, and missed paychecks, America’s COVID-19 outbreak will get worse before it gets better. On Sunday, Trump reluctantly extended nationwide social distancing guidelines to April 30; on Tuesday, he conceded that the next two weeks will be “very, very painful,” and the White House announced its official projections of between 100,000 and 240,000 deaths. As the plight of incarcerated people becomes more serious, the chorus of voices encouraging the president to grant clemency is only going to get louder. The question is whether, this time, he’ll actually listen.

Jay Willis is a senior contributor at The Appeal.