Ditching the Bondsman is Only Part of the Battle for Bail Reform

The five states that have done away with commercial bond outlets still struggle with inequity when it comes to cash bail.

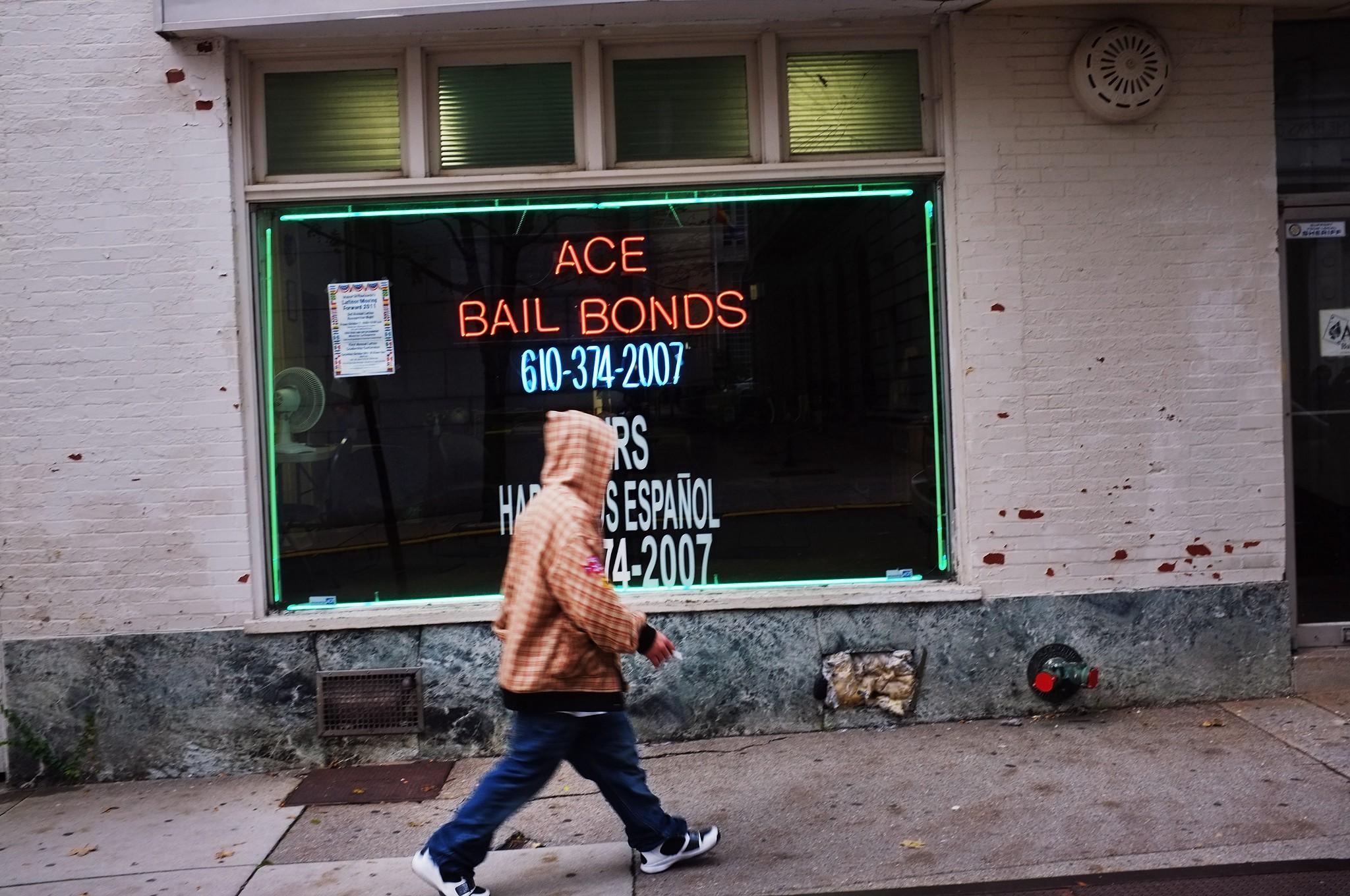

Of the criminal justice system’s many characters, the bounty hunter is perhaps the most cartoonish. Tasked with chasing down and capturing those who don’t — or can’t — pay back their debt to commercial bail outfits, this Old West relic has spawned multiple popular TV series. It’s easy to see why commercial bail and bounty hunters are emblematic of the ills of the cash bail system, which have increasingly come under fire from those pushing for criminal justice reform.

While financial incentives questionably drive many parts of the criminal justice system, the perversity of profiting from incarceration is laid bare in the bond industry, in which people who haven’t yet been charged with a crime pay a nonrefundable fee for their freedom. Five states in the U.S. have done away with commercial bail bonding, either by statute or by changing the way courts collect cash bail: Illinois, Oregon, Kentucky, Massachusetts, and Wisconsin. Getting rid of for-profit bail shops may be an important step toward amending the many facets of the bail system that work against the low-income people who are most likely to be locked up. But organizers in states without commercial bonds are struggling with many of the same issues as those in states where the practice is still legal.

“What we have is a court system that is itself profiting off of the bail program, which creates a perverse incentive for the government,” says Sharlyn Grace, co-founder of the Chicago Community Bond Fund, which pays bond for those in Cook County jail who are unable to bail themselves out.

While Illinois made bounty hunting illegal in 1963, Grace says “deposit bonds” paid to the court to bail someone out of jail still echo the commercial system. For example, if a judge sets bail at $100,000, a defendant must pay 10 percent to the court to get out of jail. Of that ten percent, the court clerk keeps $1,000 whether or not the person shows up for their court hearing. In states where they are allowed to operate, bail bondsmen do the same thing.

“There’s no large insurance companies in the background making profits, but the fact is that the court is deriving part of its budget from collecting money from people pretrial, and people are forced to pay or sit in jail,” Grace tells In Justice Today.

In February, an Illinois lawmaker introduced legislation that would do away with cash bail for any person charged with a nonviolent offense. The proposal, which ultimately failed, faced significant pushback from county court clerks, according to Grace. They argued that the courts relied on the funds from deposit bonds to function. “[Getting rid of commercial bonds] doesn’t eliminate the fact that someone’s collecting money, and those entities may protect their interests,” says Grace.

In Wisconsin, Nino Rodriguez, an organizer with Free The 350 Bail Fund, struggles with many of the same issues faced by bail fund organizers in states that still have commercial bail. In states that have abolished for-profit bail bonding, Rodriguez says that “bail amounts tend to be lower … but that doesn’t mean they’re affordable.”

Rodriguez and his fellow organizers estimate that 1 out of every 5 people in Dane County Jail are there only because of unpaid money bail. (Nationally, three out of every five people in jail are there because of their inability to pay their way out.) Though the fund has only existed since August 2017 and has bailed out 3 people, Rodriguez has already witnessed firsthand the challenges facing those who are unable to pay their bail. Judges and commissioners who assign bail are mandated by Wisconsin state statute to consider a range of factors, including a defendant’s ability to pay. Rodriguez and his collaborators have recently begun court-watching to see if the process is unfolding as it should during a defendant’s initial appearance in court.

“I don’t recall seeing a serious inquiry [by the court] into ability to pay,” says Rodriguez.

Dane County’s justice system is also a stark example of the racial disparities found in local jails throughout the country — particularly when it comes to who winds up sitting in jail because they are unable to pay their bail. A 2015 study found that black Madison residents were over 10 times more likely to be arrested than their white counterparts, even though they make up just 7 percent of the city’s population.

Amanda Liepold, a member of the Madison, Wisconsin National Lawyers Guild chapter who works with Free The 350 Bail Fund, echoed Rodriguez on this point. “Don’t assume that simply because you’re going to abolish bail bondsmen that your bail programs are now going to be just and free of bias and disparity,” she says as a word of warning to states that might consider following Wisconsin’s path.

Recently, Clatsop County, Oregon District Attorney Josh Marquis boasted on Twitter that his state was the first in the country “to abolish cash bail.” Marquis inaccurately conflated the elimination of commercial bond companies with doing away entirely with the state’s cash bail system — two vastly different reforms. While the bald profiteering of bail outlets makes them an obvious target for the reform movement, what’s happening on the ground in states like Wisconsin and Illinois illustrate that eliminating commercial bond is only a partial fix. (Of the states without commercial bail, Oregon appears to be the only one without a community bail fund movement.)

“There are still definitely injustices in the system even though we don’t have bondsmen [in Wisconsin],” says Liepold. “There are still folks sitting in jail who shouldn’t be.”