Dispatch: A Light at the End of the Tunnel for Juvenile Lifers in Pennsylvania

On Labor Day 2017, Giovanni Jerry Reid of Philadelphia was released from Graterford Prison in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania. He had served 26 years of a life sentence without possibility of parole, imposed when he was only 16 years old. On that warm, sunny morning, as he took his very first steps as a free adult, […]

On Labor Day 2017, Giovanni Jerry Reid of Philadelphia was released from Graterford Prison in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania. He had served 26 years of a life sentence without possibility of parole, imposed when he was only 16 years old. On that warm, sunny morning, as he took his very first steps as a free adult, Giovanni was greeted by his family, his friends, and his lawyer in an emotional reunion. Giovanni Reid is not the first, nor will he be the last, “juvenile lifer” to leave prison behind. There is a quiet drama unfolding in Pennsylvania as more than 500 men and 10 women, many now in their 50s and 60s, are re-sentenced. Many will return to their communities.

Pennsylvania is ground zero in the struggle to free the last of the victims of one of the most egregious sentencing schemes of the “tough on crime” era: the sentencing of juveniles as young as fourteen to life without possibility of parole (JLWOP). Pennsylvania sentenced more children to die in its prisons than any other place on earth. Even after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 2012 in Miller v. Alabama that mandatory JLWOP was a violation of the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment, Pennsylvania, unlike other affected states, refused to make the ruling retroactive, leaving hundreds of juvenile lifers still serving unconstitutional sentences. It took another four years for the Supreme Court to hold that its ruling in Miller was retroactive, and Pennsylvania was finally compelled to begin the process of resentencing and releasing the hundreds of men and women who had grown up in prison.

As they emerge from what they had always believed would be a sentence of “death by incarceration,” these men and women are reentering a world of cell phones, email, and social media — inventions that existed only in the realm of science fiction when they were locked up. But it’s not only technology that has changed. The past decade has seen the rapid expansion of a new human rights movement led by the formerly incarcerated. And those of us on the outside have been fighting hard to provide those on the inside with the resources they will need to make a smooth transition: housing, employment, education, health care, emotional support, and also the opportunity to join our struggle. We understand how important it is to help our brothers and sisters rebuild their lives, not only out of a powerful sense of empathy, but also to expose the lie upon which mass incarceration is based. The unconscionably long prison sentences that characterize the American criminal justice system have little to do with protecting public safety, and much to do with continuing centuries of racial and class subjugation. Ending JLWOP is just the first act in the much longer drama of radically shortening criminal sentences across the board.

Pennsylvania’s juvenile lifers experienced their first glimmer of hope on March 1, 2005. That was the day the U.S. Supreme Court decided that the execution of people who were under the age of 18 when their crimes were committed violated the Constitution. A group of juvenile lifers at Graterford Prison took note. Although the ruling in Roper v. Simmons did not directly apply to them, they saw a crack in the previously impregnable wall of death by incarceration in Justice Kennedy’s majority opinion. He wrote, “When a juvenile offender commits a heinous crime, the State can exact forfeiture of some of the most basic liberties, but the State cannot extinguish his life and his potential to attain a mature understanding of his own humanity.” Couldn’t Justice Kennedy’s reasoning apply to them as well? They started group called Juvenile Lifers for Justice. John Pace, who was released in February of this year after 31 years of incarceration, was one of the founders. “We wanted to keep an eye on the legal landscape and track how the issue of juvenile culpability was evolving,” he explains.

Next came the Graham v. Florida decision in 2010 in which the Court ruled that juveniles could not be sentenced to life without parole for non-homicide crimes. The crack in the wall got a little bigger. In 2012 the crack became a potential escape hatch when the Court ruled in Miller v. Alabama that the 8th Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment applied to all mandatory juvenile LWOP sentences. Despite the fact that the Court was silent on the question of whether the Miller ruling was retroactive, the men in Juvenile Lifers for Justice began to plan for their own release. “We wanted to be a good example, to not re-offend, and to create opportunities for each other as we came out,” said Pace. And for that to happen, planning needed to start right away. Based on what they had learned from the lifers and their families, two young lawyers, Lauren Fine and Joanna Visser Adjoian, founded the Youth Sentencing & Reentry Project which would be instrumental in guiding the juvenile lifers through the re-sentencing, parole and reentry process.

It took another four years for juvenile lifers in Pennsylvania to see a light at the end of the tunnel. Pennsylvania was one of only four states that did not apply the Miller decision retroactively. But in 2016, the state was compelled to do so when the Supreme Court held in Montgomery v. Louisiana that its ruling in Miller was retroactive. Finally, the re-sentencing and release of juvenile lifers got underway. As of September 2017, 125 people had been re-sentenced and 76 had been released on parole. They join the more than 300,000 returning citizens in Philadelphia alone.

Paradoxically, the very extremity of the situation in Pennsylvania has given birth to a dynamic and diverse sentencing reform movement, driven in large part by the active participation and leadership of formerly incarcerated people — people like J. Jondhi Harrell, Director of the Center for Returning Citizens and Reuben Jones, Director of Frontline Dads, both of them graduates of JustLeadershipUSA’s Leading with Conviction program. John Pace, who cut his teeth as an organizer while still serving a life sentence, has organized a peer-support group to help his brothers adjust to life on the outside. He explains that they understand very well their responsibility to “do no harm.” Recognizing the incredible potential to bring about radical sentencing reform in Pennsylvania, JustLeadershipUSA held an Emerging Leaders training in Philadelphia last April for 35 formerly incarcerated people, John Pace and other juvenile lifers among them.

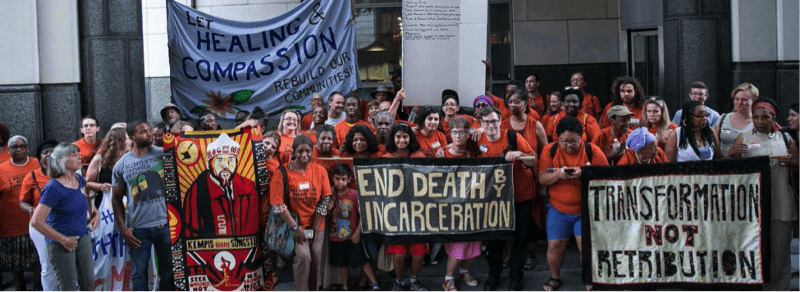

On October 25th, hundreds of Pennsylvanians, under the umbrella of the Coalition to Abolish Death by Incarceration, rallied at the state capitol in Harrisburg, demanding an end to all LWOP sentencing in the state. Pennsylvania has 10 percent of all the people in the country serving life without possibility of parole sentences. They heard a message from Felix Rosado, a member of Right 2 Redemption, an organization inside Graterford prison:

“Life without parole says that in no amount of time and with no degree of effort can 50,000 people across the U.S. — and over 5,000 in PA — ever rise above their worst moment and become worthy of life outside towered walls and razor-wired fences. To be deemed forever irredeemable goes against what it means to be human.”