Despite “Public Health” Messaging, Law Enforcement Increasingly Prosecutes Overdoses as Homicides

In response to a surging overdose crisis, prosecutors are doubling down on draconian drug induced homicide statutes. On November 28, 2014, 28-year-old Edward Martin was found dead inside a Quiznos bathroom in Littleton, New Hampshire. Next to his body was a syringe and spoon with which he used to inject a potent batch of heroin […]

In response to a surging overdose crisis, prosecutors are doubling down on draconian drug induced homicide statutes.

On November 28, 2014, 28-year-old Edward Martin was found dead inside a Quiznos bathroom in Littleton, New Hampshire. Next to his body was a syringe and spoon with which he used to inject a potent batch of heroin that turned out to be laced with illicitly manufactured fentanyl, a synthetic opioid 50 to 100 times more potent than heroin. While such scenes are now tragically common, the prosecutorial aftermath compounds the human toll of the opioid crisis.

Before Michael Millette, 55, sold Martin the bag of heorin, he warned him to be careful because it was a strong batch. “I told him, ‘Listen, this stuff is really good, just do a tiny line, it’s very strong,’” Michael recalled in a profile written by the Drug Policy Alliance published on November 7th. The two men were friends, often confiding in each other about their shared experience of being addicted to opioids — how they felt sick and tired of feeling sick and tired.

Their friendship was irrelevant to Littleton Police Department and the New Hampshire Attorney General’s Drug Task Force, which by December 2014 had pinned Martin’s death back on Millette using a draconian law developed during the crack-cocaine era, “Sale of a Controlled Drug Resulting in Death,” otherwise known as drug-induced homicide. On October 26, 2015, after spending nearly a year in jail, Millette — a drug user who was selling merely to support his own addiction — pled guilty to selling fentanyl that resulted in Martin’s death. He was sentenced in Grafton County Superior Court to spend the next 10 to 30 years in New Hampshire State Prison.

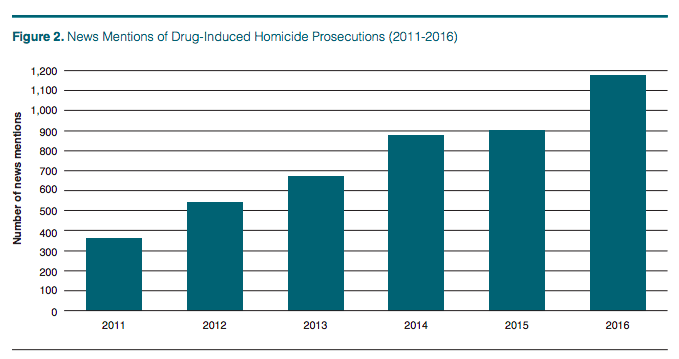

In the midst of America’s deadliest drug crisis, cases like Millette’s are spiking across the country. Drug induced homicide prosecutions increased by more than 300 percent in just six years, from 363 in 2011 to 1,178 in 2016, according to an analysis of media mentions outlined in a new report by The Drug Policy Alliance, a New York-based non-profit. Hailed by prosecutors as a strong message to dealers, drug induced homicide cases instead create a chilling effect among drug users, deterring them from calling 911 during an overdose, effectively undermining the so-called “public health” response to America’s worsening overdose crisis.

“Drug induced homicide is couched as a way to respond to the overdose crisis, but prosecutors are not held accountable for proving whether these laws are effective,” said Lindsay LaSalle, Senior Staff Attorney at the Drug Policy Alliance and the report’s author. “There is not a shred of evidence that these laws are effective at reducing overdose fatalities.”

In fact, research shows these laws are not only ineffective, but that they exacerbate the very problems they purport to solve. Of those who have witnessed an overdose, more than half reported they are reluctant to dial 911, citing fear of legal consequences, according to a 2017 study published in the International Journal of Drug Policy. Drug-induced homicide prosecutions undercut the utility of 911 Good Samaritan Laws, which provide a safe haven for people seeking medical assistance during an overdose, LaSalle said.

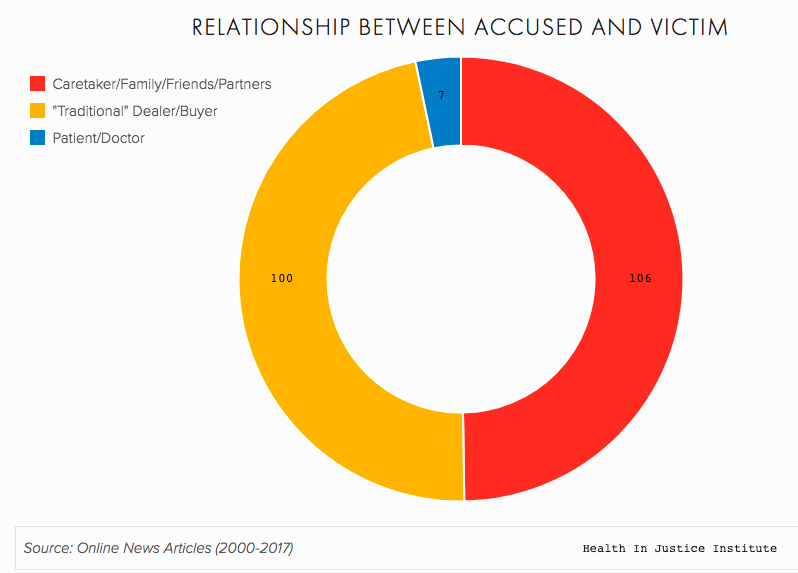

Rather than prosecuting upper-echelon drug distributors, prosecutors often charge friends and romantic partners of the overdose victim, according to an analysis by Health In Justice, a policy institute out of Boston’s Northeastern School of Law tracking punitive drug policies such as drug-induced homicide and involuntary commitment for drug users. “Fewer than half of cases we analyzed involved a traditional buyer/seller relationship,” said Leo Beletsky, lead investigator at Health In Justice, and an Associate Professor of Law and Health Sciences at Northeastern University.

Both analyses by Health In Justice and the Drug Policy Alliance also found a familiar, racialized policing pattern. Even though drug users tend to purchase drugs from members of their own race, class and peer group, more than half of all drug-induced homicide cases mentioned in the news involved a person of color as a dealer and a white overdose victim, according to Health In Justice. Drug Policy Alliance’s LaSalle noted that in a 94 percent white suburban county near Chicago, 35 percent of drug induced homicide cases were brought against people of color.

In the case of Martin and Millette, one life was lost to an overdose and the other was lost to a miscarriage of justice. Every dollar spent prosecuting drug-induced homicide cases is money that could be better spent providing treatment and preventing overdoses from occurring in the first place.