Jail Deaths Are Just One Reason To Invest In Jail Alternatives

Jeffrey Epstein’s apparent death by suicide highlights the problems of adequate mental health care and monitoring in jails nationwide.

Spotlights like this one provide original commentary and analysis on pressing criminal justice issues of the day. You can read them each day in our newsletter, The Daily Appeal.

On Saturday, Jeffrey Epstein died at the Metropolitan Correctional Center, the federal jail in Manhattan, in what appears to have been a suicide. Epstein’s death set off conspiracy theories among people who believe it is simply impossible that a defendant in a high-profile case, who had previously attempted suicide and been placed on suicide watch, would have been allowed to take his own life. He would have been under strict supervision, these theories go, and therefore the more likely explanation is that Epstein, whose case was likely to expose the names of many of his wealthy and powerful connections, had been targeted in jail.

In a matter of hours the New York Times reported that Epstein was no longer on suicide watch at the time of his death, though he had been for a few days after what was believed to have been a suicide attempt. He was in a cell by himself in protective housing, a form of solitary confinement, although, according to MCC protocols, he should have been in a cell with another person.

Also in a matter of hours, journalists, commentators, and experts started to point out that suicide in jail, which should be rare, is in fact a common event in the United States. The careful supervision that people imagined Epstein to have been under too often does not exist. As Lindsay M. Hayes of the National Center on Institutions and Alternatives wrote in The Atlantic yesterday, about the response from criminal justice experts: “Suicide has been a lingering problem in detention facilities, and systemic factors—such as inattention, understaffing, or inadequate training—generally offer a simpler explanation for a prisoner’s death than nefarious intent.”

The truth is correctional facilities routinely fail those incarcerated. An examination of deaths in correctional facilities, and especially jails, across the U.S. demonstrates how completely guards and staff neglect, ignore, and compromise the health of those they are assigned to supervise. In 2016, the Huffington Post did just this. In the year following Sandra Bland’s death in a Texas jail, Dana Liebelson and Ryan J. Reilly found, 811 people had died in jail. One-third of those deaths were by suicide.

This year, The Appeal has reported on jail deaths in recent years in Duchesne County, Utah; Orange County, California; Boyd County, Kentucky; Erie County, New York; Harford County, Maryland; Cuyahoga County, Ohio; the Hampton Roads Regional Jail in Portsmouth, Virginia; and New Orleans’s newest jail, the Orleans Justice Center.

The immediate culprit could be a failure to treat what would have been treatable medical conditions; a failure to recognize mental illness and provide adequate care; placement in solitary confinement, known to cause psychological deterioration; or violence on the part of jail staff or other incarcerated people. All these factors add up to a reality where people in jail, rather than being protected from harm, are uniquely exposed to it.

We know that suicides have been the leading cause of jail deaths since 2000 and that the number peaked in 2014, the last year for which figures are available. Some reported suicides have attracted attention—that of Bland in 2015, after a state trooper had her detained after pulling her over for a traffic violation, prompted the state to change its laws around mental health screenings. Many more are ignored.

On average, 1 in 5 people in jail around the country is believed to have a mental health condition. Too often, people end up in jail when the attention they need would be better provided by other systems. This is the argument being made in Los Angeles right now, one of the jurisdictions where close to a third of all people in custody, more than 5,000 people, have a history of mental illness.

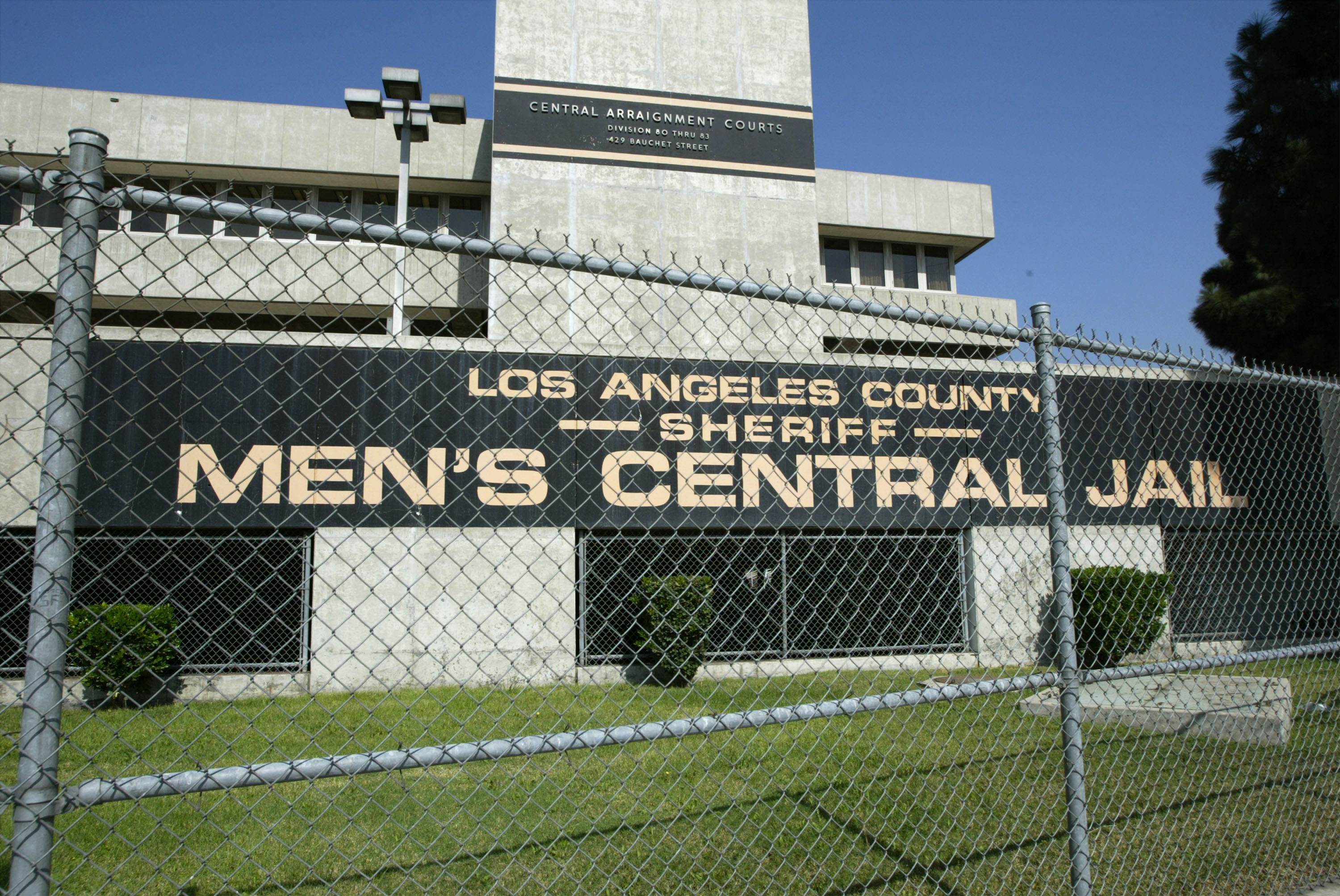

The county Board of Supervisors will vote tomorrow on a motion to cancel a $1.7 billion contract for the construction of a mental health treatment center on the site of the Men’s Central Jail. The motion and the vote represent a victory for theReform LA County Jails coalition that has fought against the construction of the large facility, arguing that it would be a jail by another name. Patrisse Cullors, a Black Lives Matter co-founder and the chairperson of the coalition, told Lauren Gill of The Appeal in an email, “We are one step closer to that closure and to building a holistic model for mental health care in Los Angeles County.”

For several years, the county has been considering the best alternative to the decrepit and dangerous Men’s Central Jail. (A total of over 17,000 people are incarcerated in all LA county jails combined, the highest number of people in jail of anywhere in the country.)

The earliest iteration of the plan was to tear down the jail and build a new jail focused on treatment in its place. Last year, that plan was altered so that the new building would, instead of a jail, be a mental health treatment center. That plan passed by a 3-2 vote. Some hailed it as an effort to move away from incarceration as a response to mental illness and offer treatment instead to people held pretrial in LA County.

But critics of the plan said it was jail-building in the guise of mental health care. They criticized the plan for one large facility, arguing that community-based treatment centers were what would actually serve those most in need. And they disagreed with the expenditure on the order of billions of dollars on what was, in effect, another jail.

As the Los Angeles Times put it in an editorial in June: “There is concern that the jail plan still lives—that the only change will be calling it a hospital. But a jail is still a jail and falls well short of the community-based system of mental health, substance abuse and behavioral care that was long-ago promised, and has been long needed.”