‘Let Me See That Waistband’

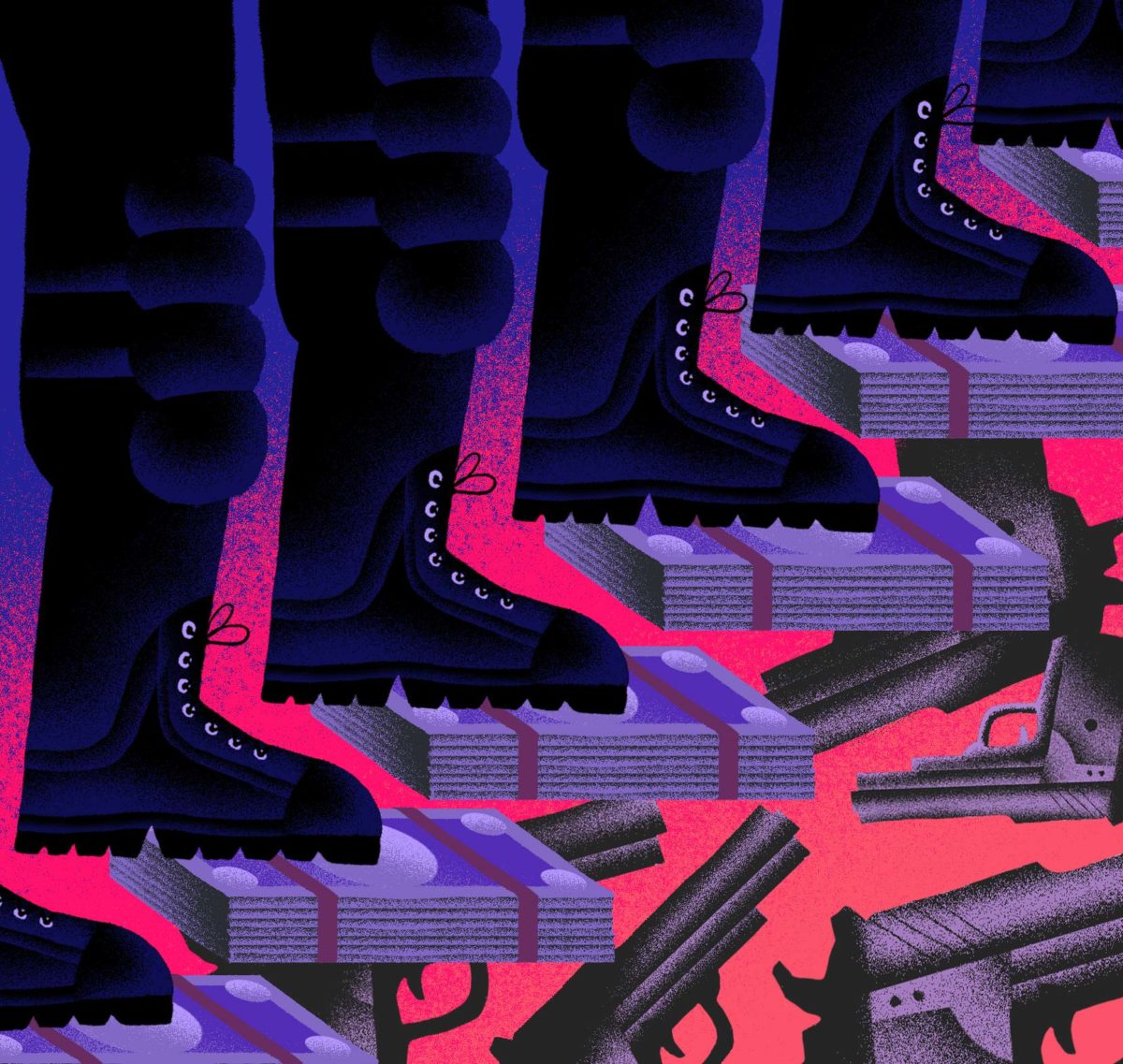

A veteran D.C. police officer says the Metropolitan Police Department’s Gun Recovery Unit deploys illegitimate tactics in a war on guns that have fostered an adversarial relationship between the department and the communities they are supposed to serve.

Around 11:30 p.m. on Jan. 12, 2020, officers with the Metropolitan Police Department’s Gun Recovery Unit (GRU) turned their unmarked Chevy Malibu onto a residential street in Washington, D.C., where they spotted Dalonta Crudup walking with a backpack slung around his shoulder.

Crudup, a 23-year-old Black man, noticed the Malibu and shifted his backpack to both shoulders. According to a statement of probable cause, that was enough for the plainclothes GRU officers to jump out of their vehicle and stop Crudup.

“You don’t got no weapons on you?” one officer asked Crudup.

Crudup lifted his shirt and showed the police his waistband. There was no gun there. He told them he had marijuana—which is legal in D.C.—on him. Multiple times, the police, all wearing tactical gear, asked Crudup if they could search his backpack for weapons. Each time, Crudup told them no.

Then one of the cops claimed they heard something in the backpack. They patted it down, said they felt marijuana inside, and took the backpack. The officers said they found a gun and placed Crudup under arrest.

After his arrest, Crudup was offered a plea deal by the United States attorney’s office but refused to plead guilty. The police had no justifiable reason to stop him, let alone search him, and he knew that.

“What was written on the probable cause affidavit was just egregiously unconstitutional, in my opinion. I mean, he literally was stopped because he was walking while Black with a backpack,” Sweta Patel, one of Crudup’s lawyers, told The Appeal. “They really didn’t give any probable cause, reasonable suspicion, or anything.”

Fifteen minutes after Crudup declined to plead guilty, prosecutors dropped his gun charges.

Crudup is one of four plaintiffs in an ongoing class action civil rights lawsuit that attorneys Patel and Michael Bruckheim filed in federal court against the D.C. government. The lawsuit alleges that the GRU—which focuses on the interdiction and recovery of illegal weapons and the apprehension of people involved in illegal gun crime—has a policy of stopping, frisking, and searching Black people without reasonable suspicion or probable cause, and that they fabricate information to justify the stops, frisks, and searches. According to the lawsuit, despite D.C. having some of the strictest gun control measures in the country, the GRU has a “practice and custom of treating African American people as though they all carry illegal handguns.”

The lawsuit says the GRU officers use a person’s presence in a “high crime” neighborhood as a reason to approach them and often cite a person shielding themselves from officers jumping out of an unmarked car or running as further justification for a stop. When GRU officers ask if they can search someone, they often characterize how that person responds to the question as “suspicious” in order to justify a search, even if the person did not consent.

In November, attorneys for the city government wrote in a motion filed with the court that the “plaintiffs’ claims have no merit and should be dismissed” in part because “the officers had reasonable suspicion to support the stops and searches.” They said that none of the plaintiffs disputed that they were in possession of a firearm without a license and also denied that the GRU has a policy of engaging in unconstitutional stops and searches.

But activist groups such as Black Lives Matter D.C. and Stop Police Terror Project D.C. say the GRU conducts warrantless searches, uses force almost exclusively against Black residents, and commits fatal police shootings. In 2018, two officers were investigated—and removed from the unit—after a questionable search of the backyard of the uncle of Jeffrey Price, a 22-year-old who died when his dirt bike collided with a police cruiser in Northeast D.C. In March 2020, Price’s mother filed a civil rights lawsuit against the officers involved in the fatal accident; the lawsuit is ongoing. And there have been several lawsuits alleging that the GRU performs “unjustified sexually invasive” searches and regularly engages in “jump-outs” targeting Black residents.

The leadership’s focus on GRU is stat driven. Leadership focuses on how many guns GRU recovers and if an arrest is made with the recovery. There is very little, if any, review of how the gun was recovered or how the arrest was made.

Anonymous a former command-level official with the Metropolitan Police Department

Now, a nearly 30-year Metropolitan Police Department veteran is speaking out about the GRU, blasting the unit as statistics-driven and engaged in a pattern and practice of illegal stop-and-frisks. The Appeal obtained a five-page letter written by the former command-level official about the GRU and the roles that this person says former chief Peter Newsham and current chief Robert Contee played in enabling them.

“These outdated practices have resulted in the adversarial relationship between the community and the police department,” the veteran wrote. “Sadly, the police leadership’s response to community concerns is to double-down on the practices that are of most concern to the community.”

The Appeal also spoke with the veteran, who said they were moved to write the letter out of concern for D.C.’s residents whose trust has been violated by the police, especially young Black men whose lives are being “ruined” by gun charges “inhibiting their future.” They requested anonymity out of fear of retaliation. Last year, Sgt. Charlotte Djossou alleged in a lawsuit that she was retaliated against for blowing the whistle on department abuses that included narcotics division supervisors instructing officers to target young Black men in low-income neighborhoods for jump-outs and reclassifying felonies as misdemeanors in order to improve crime statistics.

“The leadership’s focus on GRU is stat driven,” the veteran wrote. “Leadership focuses on how many guns GRU recovers and if an arrest is made with the recovery. There is very little, if any, review of how the gun was recovered or how the arrest was made.”

In early 2019, former chief Newsham defended the department’s use of stop-and-frisk as “constitutional.” In March of this year, Chief Contee said the department has not used jump-outs as a tactic in years, according to the Washington Post. But the veteran says the GRU violates residents’ Fourth Amendment rights and the practice is central to its gun seizures.

A “dubious tactic employed by GRU is jumping out on groups of people and fishing for statistics,” the veteran wrote. “Members of GRU would drive up to an area where multiple people were hanging out, jump out of the truck, and force everyone present to submit to stop and frisk without any articulable reason for being stopped and frisked other than their mere presence at the scene.”

The Metropolitan Police Department did not respond to The Appeal’s request for comment about GRU’s tactics and allegations of civil rights violations by the unit. But Kristen Metzger, deputy director of the department’s communications office, emailed a statement to The Appeal emphasizing that “under Chief Robert Contee’s leadership, MPD has begun examining the Department’s strategies related to guns and violence. Chief Contee emphasizes a strategic approach aimed at getting the right guns out of the wrong hands in our communities. MPD has already shifted resources to focus on an intelligence-based policing approach to identify, interdict and interrupt violent offenders within the District.”

In the letter, the veteran accused the department of misrepresenting data regarding police stops gathered after the 2016 passage of the Neighborhood Engagement Achieves Results (NEAR) Act. The act compels the collection of information about the stop—such as the reason it happened, how long it lasted, whether it resulted in an arrest, and the race of the person stopped—and the release of that data to the public. But the department has a troubled history with compliance.

In February, ACLU-DC sued the police department. “MPD has failed to uphold its promise” of complying with the NEAR Act, the organization wrote in a statement, and “as of February 2021, MPD has not published any data since March 2020, and its published data only covers 6 months in 2019. No data on stops conducted in 2020 has been published.”

Days after the ACLU-DC filed the lawsuit, the police released stop data from Jan. 1 through June 30, 2020. The department released data for the rest of 2020 the following month and promised a comprehensive 2020 stop data report in April. The 2019 data released in March 2020 was also released after a 2019 ACLU-DC lawsuit.

The veteran says in their letter that when a judge ordered the release of stop data after the 2019 lawsuit, department command attempted to “manipulate the results” in order to evade accusations of racial bias. According to the veteran, one commander told officers to perform more stops in parts of D.C. with white residents “to balance the number of pedestrian stops against black individuals in her district.” Another commander instructed police to perform more car stops of white drivers “to neutralize the number of vehicle stops made against black individuals in his district.”

The result was more racial profiling rather than a reduction in stops: “Neither commander had a goal of decreasing unnecessary stops against blacks, only to offset the total number by increasing target stops against whites.”

Stop data shows that between July 22, 2019, and Dec. 31, 2019, 72 percent of all the department’s stops were of Black residents and 87 percent of “non-ticket stops” were of Black residents. Forty-six percent of D.C.’s population is Black. A 2020 National Police Foundation report revealed that between August 2019 and January 2020, 87 percent of stops, 91 percent of arrests, and 100 percent of use-of-force incidents by the Narcotics and Specialized Investigations Division, which includes GRU, were of Black people.

Although the Metropolitan Police Department is hesitant to release stop data as required by the NEAR Act, the veteran wrote, it closely tracks gun seizures, and command officers are held accountable for those statistics: “If there is a drop in the total recoveries as compared to the prior month, the Chief inquires as to why there is a decrease and what the Commanders plan to do to restore the number of recoveries. What is apparently absent in the agency’s review of gun recoveries is how the guns were recovered, specifically the constitutionality of the recovery.”

Each week, the department’s gun seizures are released publicly with details about each gun, the name of the person who allegedly possessed the gun, what they were charged with, and often a photograph of the gun.

Alex Vitale, a professor of sociology at Brooklyn College and the author of “The End of Policing,” told The Appeal that this focus on data conflates transparency with accountability.

“Both government officials and a lot of legal advocates come around to this idea that since we can’t really change anything—or we don’t really want to change anything—let’s collect some data,” Vitale said. “But we don’t need to haggle over the data. We need to quit engaging in this kind of enforcement.”

“The impression it leaves me, as a resident of the city,” said Patrice Sulton, executive director of D.C. Justice Lab and a member of the DC Police Reform Commission, “is that people in leadership care most about the number of guns they collected. That’s the metric they are paying attention to.”

You remember they used to put all of the drugs and the money out on the table? Now it’s all about guns right?

April Goggans Black Lives Matter D.C.

According to department data, Dalonta Crudup’s Smith & Wesson M&P Bodyguard .380 caliber handgun was one of 46 guns the GRU recovered between Jan. 6 and Jan. 13 last year.

April Goggans of Black Lives Matter DC told The Appeal that the tactic of displaying gun seizures for the public is an example of how the police department’s “war on guns” mirrors the numbers game that fuels the war on drugs.

“You remember they used to put all of the drugs and the money out on the table?” Goggans said. “Now it’s all about guns right? And people in the city care about guns so they’re like, ‘Get them off the street’ but you try to tell people that there’s this many stops, this many searches, and they’re not finding a weapon most of the time—and the homicides are going up.”

A February report by the District Task Force on Jails & Justice analyzed 2019 NEAR Act data and found that out of 1,717 consent searches, police seized just 19 guns. And 1,606 of those stops (94 percent) did not result in contraband seizures.

In 2007, the year the GRU was formed, there were 181 homicides in D.C. In 2020, there were 198.

In the letter, the veteran expressed concern about a highly publicized June 2018 incident in which the GRU searched a group of Black men hanging out in front of Nook’s Barbershop in the majority-Black Ward 7. Video of the incident posted by Black Lives Matter DC showed plainclothes GRU officers attempting to conduct a search of a man in the group. When the man put his arms up, an officer pulled a gun from his pants. Officers then told the group that they had probable cause to search all of them for weapons.

The officers “then turned their attention to the other men present and forced them all to submit to a frisk,” the veteran wrote. “The justification the officers gave, which was supported by the Chief, was if there was justification to frisk one person, there was justification to frisk everyone.”

No other guns were seized by the GRU in front of the barbershop that day. Ward 7 commissioner Anthony Lorenzo Green said residents believed that police planted the weapon seized that day—a BB gun, which is illegal to possess in D.C—and that it was taken from an undercover officer, not a civilian, on the scene. “No one was arrested because none of the other men had drugs or firearms in their possession,” Green wrote in a June 24, 2018, letter to then-chief Newsham. “The officers acknowledged they did not get a call for loitering… I am convinced your department is not collecting that [NEAR Act] data because you want to hide the fact that your officers are making up opportunities to harass black and brown people in our city.” The Metropolitan Police Department denied that the man was an undercover officer and that the gun was planted.

During a 2018 D.C. City Council hearing held as a result of the incident, then-Councilmember at-Large David Grosso asked Newsham, “Why are we using the same tactics 30 years later?”

“It’s not the same tactics,” Newsham insisted.

Contee, then assistant chief, defended the incident to the council. He said it was an example of “intelligent policing,” which he differentiated from jump-outs because the cars parked in front of Nook’s had tinted windows and officers observed people going in and out of the vehicle. That was reasonable suspicion to search the group, Contee explained.

BLM DC’s Goggans told The Appeal that the tactics displayed in the Nook’s incident are commonplace within the GRU. She said the unit also detains people who don’t have weapons on them until the person can point them in the direction of a gun or someone who has a gun. “With Gun Recovery, they will get guys and they will say, ‘We’ll let you go if you call friends to bring a gun,’” Goggans said.

The veteran wrote that a 2018 video recorded by Ward 8 Councilmember Trayon White is illustrative of this GRU tactic. The video shows two teens detained for allegedly having an empty magazine.

“The GRU members told the teens they would not be released unless they disclosed the location of a gun or a person armed with one,” the veteran wrote. “MPD’s leadership has been made aware of this dubious tactic yet has taken no corrective action.”

Goggans described the GRU engaging in targeted harassment such as calling out the names of people while on patrol to “thank” them for talking to them—a clear implication that they are informants, which would threaten their safety in the neighborhood.

“The police see Black folks, people in this community, as enemy combatants. So once you’ve determined somebody is an enemy combatant, then the way you engage them is different,” Goggans said.

This “warrior” approach to policing is embraced by the GRU, Goggans said. She cited a 2016 photo of GRU members posing in front of a flag with “Gun Recovery Unit” written on it, along with the image of a skull with a bullet hole between its eyes and the words “Vest Up One In The Chamber.” The photo was part of a 2017 complaint by the advocacy group Law for Black Lives. That same year, Goggans notes, Officer Vincent Altiere of a plainclothes unit called Powershift was photographed wearing a shirt featuring a Grim Reaper, a Celtic cross, which is widely used as a white supremacist symbol, and the phrase “let me see that waistband.”

Bowser can wax poetic all she wants about George Floyd, but at the end of the day, Muriel Bowser is guilty of facilitating the very same kind of racist police here that killed George Floyd.

Sean Blackmon Stop Police Terror Project D.C.

D.C.’s war on guns raises constitutional concerns—and it also comes with fatal consequences. On Sept. 3, 2020, Metropolitan Police Department officers chased, shot, and killed Deon Kay after they said they acted on a tip that someone in the area had guns in their vehicle. Officers pursued Kay, who had a gun and ran. Although a GRU officer did not kill Kay, the ACLU-DC connected his death to the police’s focus on gun seizures.

“The D.C. police department’s approach to gun recovery has been dangerous and ineffective for years,” ACLU-DC executive director Monica Hopkins said. “The tragic shooting and death of 18-year-old Deon Kay is the logical conclusion of a policy that not only meets violence with violence, but actually escalates and incites it—especially in our Black communities.”

Kay’s killing came after a summer of protests in D.C. against police violence following the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis—and months after Mayor Muriel Bowser renamed two blocks of 16th Street NW “Black Lives Matter Plaza.” Bowser, however, seemed to justify Kay’s death as a necessary part of the police department’s war on guns.

“I know the officer was trying to get guns off the street,” Bowser said. “And I know he encountered somebody with a gun.”

Sean Blackmon of Stop Police Terror Project D.C. told The Appeal that Bowser’s stance on Kay is typical of a mayor who opposed the D.C. Council defunding the police by $15 million last year, then requested that $43 million be redirected to the police budget. Blackmon also pointed out that Bowser supported “Mr. Stop and Frisk himself, Mike Bloomberg” in the 2020 Democratic presidential primary.

“Bowser can wax poetic all she wants about George Floyd, but at the end of the day, Muriel Bowser is guilty of facilitating the very same kind of racist police here that killed George Floyd,” Blackmon said.

According to FiveThirtyEight, a Black person in D.C. is 7.3 times more likely to be arrested than a white person and 13.4 times more likely to be killed by a police officer.

Yet Bowser continues to support a 2019 citywide initiative called felons-in-possession that makes gun possession a federal charge for people with felony records, even though U.S. prosecutors revealed last year that the policy was enacted only in majority-Black districts. D.C. Attorney General Carl Racine called the initiative, which exposes people to harsher sentencing, “discriminatory.” A group of Black prosecutors also opposed it because of its “negative racial and social impact,” and an April 2020 amicus curiae brief from ACLU-DC argued that the initiative “makes federal cases out of purely local criminal matters.”

Bowser and then-chief Newsham both said they did not know felons-in-possession was not being applied citywide. The initiative remains in place today and has the support of Acting Chief Contee. Biden-appointed Acting U.S. Attorney Channing D. Phillips recently announced that felons-in-possession policy would remain in place even though a former assistant U.S. attorney called it “racist, unjust and unlawful” and said that Black people comprise 97 percent of felons-in-possession charges.

The racial disparities perpetuated by these kinds of federal initiatives has been known for decades. James Forman Jr.’s 2017 book “Locking Up Our Own: Crime and Punishment in Black America” notes that during the 1990s, then-U.S. attorney for D.C. Eric Holder said of Operation Ceasefire, which encouraged police to “stop cars, search cars, seize guns”: “I’m not going to be naive about it. The people who will be stopped will be young black males, overwhelmingly.”

GRU’s strategies resemble Holder’s Operation Ceasefire. He encouraged officers to “wrangle consent,” Forman wrote, and “blur the distinction between commands that a driver must obey (such as providing license and registration, or stepping out of the car) and requests that he may decline (such as giving permission to search).”

“But it was more than fear of crime or the credibility of black law enforcement officials that sold Operation Ceasefire,” Forman continued. “Also critical was the fact that the program targeted guns, not drugs.”

The veteran criticized former police chief Newsham for not only enabling the GRU but criticizing those who questioned the unit’s tactics, including fellow law enforcement.

Newsham “blamed [prosecutors] when cases were thrown out for procedural errors as opposed to using these cases as learning opportunities to better train his officers,” the veteran wrote.

The dismissal of handgun charges against a Black man after federal prosecutors said there was no probable cause for the arrest angered Newsham, the veteran wrote. During one staff meeting, Newsham “called the USAO [United States attorney’s office] ‘soft on crime’ and stated judges were no better.”

Newsham, who is now the Prince William County police chief, responded to The Appeal’s request for comment in an email from the department’s Public Information Supervisor: “Chief Newsham believes these claims are preposterous, inflammatory and/or noncontextualized, without knowing who you spoke to or what their motive was for suggesting these things, he would be unable to make any further comments on the matter. As for Chief Contee, Chief Newsham has every confidence that he is a very capable and committed police leader who will do what is in the best interest of public safety in the District of Columbia.”

A 2018 report by the radio station WAMU that analyzed almost 500 Metropolitan Police Department gun cases filed between 2010 and 2015 showed that nearly 40 percent of those cases were dismissed.

“MPD historically, and more so over the past four years, has demonstrated a pattern and practice of unconstitutional conduct,” the veteran wrote. “Even after having these concerns brought to its attention through citizen complaints, video footage of officer conduct, dismissed criminal cases, lawsuits, and court orders, MPD took no action to institute remedial training, implement new policy, or issue any discipline to officers for Fourth amendment violations. There is no accountability for these actions but instead plenty of praise for these results.”

The veteran also argued that Contee, who replaced Newsham at the beginning of the year, was complicit in GRU policy and practices.

“He was the Assistant Chief overseeing GRU,” the veteran wrote, during a time period that includes the Nook’s Barbershop incident and the recorded incident involving two teens. According to the veteran, Contee did not make any “meaningful” changes to GRU’s roster, its policies, or its training after those high-profile incidents.

“This statement is not accurate. The incident at Nook’s Barbershop was investigated by our Internal Affairs Division and the allegations of improper stops and searches were determined to be unfounded,” Metzger of the police department’s communications office wrote to the Appeal. “MPD is committed to listening and learning from the community and recently announced a partnership with Howard University to host community listening sessions.”

They love to play those semantic games. But at the end of the day, if you’re violating my basic rights, if you’re abusing me, if you’re beating me, if you end up killing me, you could call it a pizza party—it doesn’t change what it is.

Sean Blackmon Stop Police Terror Project D.C.

On Jan. 2, Contee was sworn in as chief, and he also spoke to the media about Antonie Smith, who was shot and wounded by department officers that morning. A resident had reported Smith was armed with a handgun.

“I have a swearing-in ceremony shortly in about an hour or so, but you know, this will continue to be a fight for the Metropolitan Police Department to get illegal guns off of our streets,” Contee said.

Three hours after the shooting, the police posted a photo of Smith’s gun on the department’s Twitter account.

In the weeks leading up to the D.C. Council’s vote to confirm Contee as Chief, he began talking reform. In a March 11 interview with the Washington Post, Contee said the department needed “to think beyond just getting the gun,” and change its approach on gun policing—especially within the GRU.

“I want to be more strategic about getting the right guns out of the wrong hands. We have already shifted resources to focus on an intelligence-based policing approach to identify, interdict, and interrupt violent offenders within the District,” Contee told the Judiciary & Public Safety Committee on March 25. “The goal is to build strong criminal cases on offenders and groups to ensure those repeat offenders cannot continue to endanger our communities.”

The Post quoted an internal memo from Commander John Haines, head of the Narcotics and Special Investigations Division, which houses the GRU. “No longer are we focused on getting guns,” the memo reads. “The focus will be on those that pull the trigger and directly or indirectly harm others.”

On March 31, the Judiciary & Public Safety Committee unanimously confirmed Contee, setting him up for a vote by the council on a date to be announced.

The veteran told The Appeal that they are not surprised to see Contee defending the GRU even as he calls for gun policing reforms. In the Post, Contee said officers are not “stopping as many people as they can to get whatever guns they need” and he does not “want that to be the perception of what is happening.”

“I think he’s saying what people want to hear. By saying ‘I’m not saying you’ve done anything wrong, we just need to change everything,’ he’s towing the line, he’s telling [the officers] ‘I got your back,’” the veteran said. “Getting guns off the street is worthy, but we don’t have to violate rights. It doesn’t help to make an arrest and violate someone’s rights: The case gets thrown out, and the person goes free.”

In an email to The Appeal, Metzger pointed to the Violence Reduction Unit, formed in 2020, as an example of how changes to gun policing have already begun: “The goal of this Violence Reduction Unit (VRU) is to build strong criminal cases on offenders and groups to ensure those repeat offenders cannot continue to endanger our communities. The VRU is already seeing success with its casework and MPD will continue to work with residents to ensure that our strategies support—and don’t undermine—the vibrant and safe communities where our residents—our youth, families and seniors—can thrive and succeed.”

For Stop Police Terror Project D.C.’s Blackmon, announcing new policing strategies and new units and denying the existence of jump-outs is another way for the department to avoid responsibility for its harmful and unconstitutional practices.

“They love to play those semantic games,” Blackmon said. “But at the end of the day, if you’re violating my basic rights, if you’re abusing me, if you’re beating me, if you end up killing me, you could call it a pizza party—it doesn’t change what it is.”

Goggans recognizes that some Black residents of D.C. who endure most of the city’s violent crime are willing to “trade off” freedoms for feeling safer: “I feel like so many people are OK with [GRU] because it’s like ‘good violence’ because it feeds off the fact that people are rightfully fearful of violence.”

People accept this kind of policing because it is the only solution offered by the city and substantively funded, Brooklyn College’s Vitale explained.

“This is what we call a supply side strategy to managing gun violence, right? Gun control laws, gun interdiction, gun enforcement. But D.C. is not funding the demand side enough, which is, ‘What are we doing to work with young people so that they don’t choose to pick up guns in the first place?’” Vitale said. “Anyone Black in D.C. already knows what’s going on. I think it’s pretty clear that that they just shouldn’t be doing the vast majority of the stops and a huge amount of them are pretextual.”

Sulton told The Appeal that “the message being sent to these officers is they are to hunt guns and drugs,” and that D.C. is “trying to solve violence with violence” and “trauma with trauma.”

“We can’t afford to keep doing this,” Sulton said.

A report released this month by the DC Police Reform Commission, of which Sulton is a member, makes numerous police recommendations policy including the immediate suspension of GRU and similar specialized units “unless and until the Department produces data showing they address violent and otherwise serious crime more effectively than ordinary patrol units.”

Crudup attorney Bruckheim said that unlike Crudup and the other class action clients, most arrestees in gun cases plead out, even when their Fourth and Fifth Amendment rights have been violated. When they do not enter a guilty plea or their charges are dismissed, the weapons seizure has already been memorialized in police department data as successful.

“At the end of the day, if they find a gun, they figure, ‘You know what, we got a gun off the street. So who cares if we violated someone’s rights,’” Bruckheim said. “But the fact is the Constitution of the United States is not limited by geography. I understand how some people will say, ‘What’s the big deal? At the end of the day, they recovered contraband, the city’s a little safer and so on.’ But you can’t go about it by violating the rights of citizens, number one. No matter what.”