Why Is COVID-19 Hitting Black Communities Harder? Residential Segregation Is a Key Factor.

Segregation not only increases individuals’ exposure to the novel coronavirus, it also leaves them more susceptible to its effects and limits the quality of care they will receive, experts say.

Decades ago, when tuberculosis made a resurgence tethered to the HIV epidemic, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention sounded a seemingly hopeful note: The disease was “retreating into geographically and demographically defined pockets.”

But this was not a victory, as Dolores Acevedo-Garcia, professor of human development and social policy at Brandeis University, pointed out.

“They were literally celebrating the segregation that we have because they thought it would be ‘functional’ in terms of preventing the spread to the larger society,” she said, describing the CDC statement as “very disturbing.” These were the early days of geocoded health data, Acevedo-Garcia said, but senior health researchers were already using the method to investigate the HIV epidemic in New York City. They found that the neighborhoods that had high rates of HIV and TB were the same ones that experienced divestment of public services, dilapidated and abandoned housing, and injection drug use.

Then a doctoral student, Acevedo-Garcia wrote a landmark paper describing the epidemiological pathways between residential segregation and the spread of TB. She tested her hypothesis using data from New Jersey during the period when the disease was on the rise, finding that residential segregation indeed facilitated the higher transmissions of TB for Black and Latinx residents.

Black residents were the most frequently exposed to environments where TB incidence was high: 50 percent of Black residents lived in ZIP codes with very high TB rates, compared to 31 percent of white, 29 percent of Latinx, and 26 percent of Asian residents. They were also most frequently exposed to multiple neighborhood risk factors for TB—poverty, isolation, dilapidated housing, and crowded housing—compared to white and Asian residents. For Latinx populations, high exposure to poverty and overcrowded and dilapidated housing contributed to high TB rates. Isolation—the extent to which members of a racial-ethnic group are likely to be in contact with members of the same group—was protective for whites, but detrimental for Black residents.

Now, she worries that history will repeat itself with COVID-19. Residential segregation concentrates disadvantage and privilege into geographically defined areas, creating conditions in which whole neighborhoods are going to be more exposed to the virus than others. “I don’t want people to think that we are going to be able to ‘contain’ the epidemic because it’s in those communities,” she said.

Emerging data shows stark racial disparities in COVID-19 cases, deaths, and the toll the disease takes on individuals, revealing an all-too-common pattern to researchers.

“We are seeing now that the neighborhoods with the most COVID deaths and cases are racially segregated neighborhoods,” said Sirry Alang, professor at Lehigh University in Pennsylvania. In her hometown of Allentown, Pennsylvania, officials are mapping COVID-19 cases, and the data show the most affected wards are those with predominantly Black and Hispanic residents and some of the highest poverty rates.

“Segregation concentrates social conditions that are conducive to transmission,” says Acevedo-Garcia, who has spent the past decades studying how neighborhood conditions affect health outcomes. Her recent work examines inequities in neighborhood conditions for children.

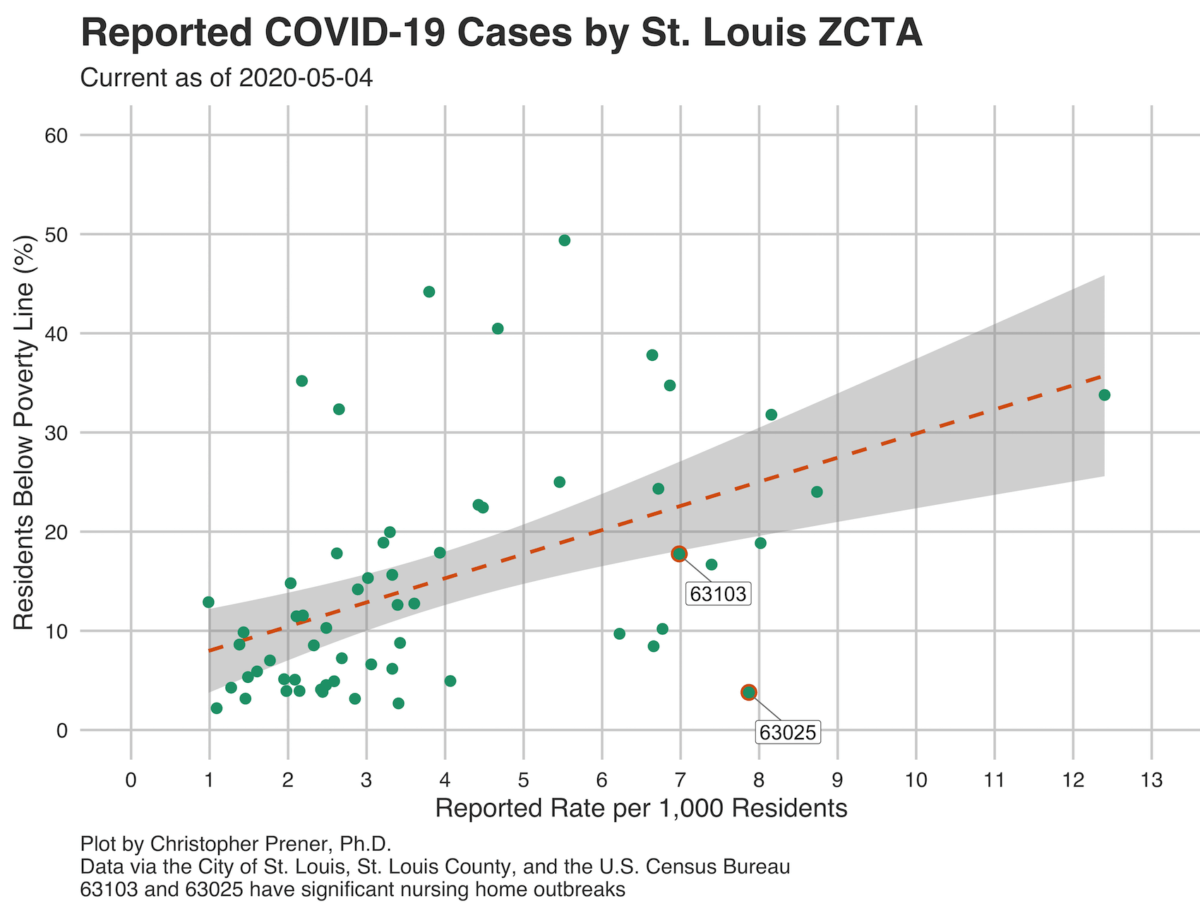

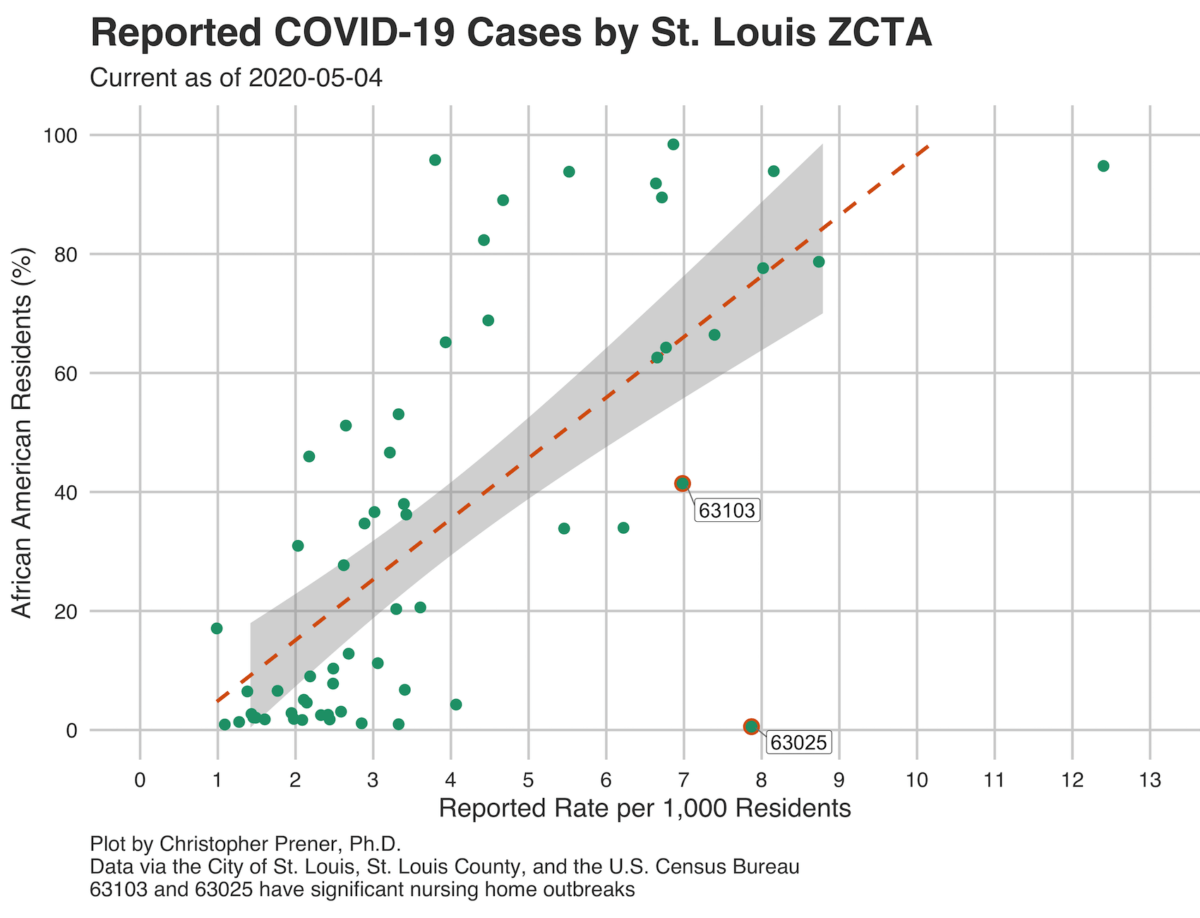

Christopher Prener, professor of sociology at St. Louis University, is mapping confirmed COVID-19 cases to ZIP codes in the St. Louis area, and finding that historically marginalized, predominantly Black neighborhoods in northern St. Louis, including Ferguson, are bearing the heaviest COVID-19 burdens.

While data collection is still in its earliest stages, he said, “we see really striking patterns in who is getting sick” and “the rates are concentrated among African Americans.”

On April 10, U.S. Surgeon General Jerome Adams told Black and Latinx communities to “step it up” in following COVID-19 prevention guidelines, and to “avoid alcohol, tobacco, and drugs.”

But experts say that pathologizing Black and Latinx people by pointing to their individual choices or “underlying medical conditions,” rather than acknowledging the deeper inequities behind racial disparities in comorbidities, plays into a false narrative.

“If you study racial disparities in health, then you know that structural racism plays a big part in terms of inequities,” said Alang, “And one of those mechanisms is residential segregation.”

Residential segregation not only increases individuals’ exposure to the novel coronavirus, it also leaves them more susceptible to its effects and limits the quality of care they will receive, experts say. And stopping the spread of the COVID-19 rests on mitigating the inequities linked to neighborhood conditions.

Most, if not all, U.S. metropolitan areas are racially segregated thanks to formal and informal practices and policies—redlining, blockbusting, and discriminatory mortgage practices—that have steered Black residents into high-poverty, less-resourced neighborhoods.

Much about a neighborhood can have an impact on health: access to healthy foods, spaces that allow opportunities for physical exercise, exposure to crime, and proximity to health care providers. For decades, public health studies have found residential segregation to be associated with adverse birth outcomes, high blood pressure, cardiovascular health, childhood asthma, and diabetes mortality.

And because educational and economic opportunities in segregated neighborhoods are severely restricted, residents are more likely to live in poverty, work service jobs, or be unemployed, and take public transportation, compared to residents in resource-rich areas.

In the age of COVID-19, this means residents of segregated neighborhoods are more exposed to the virus simply because they work jobs that cannot be done remotely and do not provide paid family and medical leave, experts say.

Only one in four U.S. workers have a job that allows them to stay home, even though that is likely to change due to the pandemic. But the ability to work from home is certainly clustered by industry, race/ethnicity, and income, according to 2017- 2018 data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Sixty-two percent of people who were in the highest income strata were workers who could work at home, compared to 9.2 percent of people in the lowest strata. The industries where people were most likely to have worked from home were professional and business services (47.4 percent), financial activities (46.7 percent), and information (45.1 percent). Compare that to the industries that had the least proportion of people who worked from home—leisure and hospitality (6.8 percent), transportation and utilities (12.5 percent), wholesale and retail trade (13.9 percent), and construction (14.4 percent).

Because urban residential segregation concentrates low-income, impoverished people in the same neighborhoods, known as concentrated poverty, people who cannot afford to stay home are clustered together in the same area, likely turning entire neighborhoods into hot spots for transmission.

“People from those neighborhoods are more likely to be unemployed or living paycheck to paycheck,” said Alang. They also have to go out more because they cannot afford to buy food and supplies in bulk. In fact, aggregated smartphone location data shows that people who lived in the highest-income locations had cut their movement almost in half by March 16, three days earlier than people living in poorer areas, according to a New York Times analysis, indicating that wealthier people are better able to shelter in place.

Segregated neighborhoods are often made up of multigenerational and multiple-adult households, she said. “One or two adults in those families are an essential worker. They are stocking the shelves in our grocery stores, they are driving the bus, they are delivering our mail and our food. So then, if a person is exposed, and they are in a multigenerational home, that just increases the overall exposure.”

These neighborhoods keep society running and allow entire privileged, typically white, neighborhoods to stay home, Alang said.

In the Times analysis, metropolitan areas with the highest income disparity also saw disparities in movement. In cities like San Jose, Boston, and Washington D.C., for example, people in high-income areas stopped movement, while those in low-income areas reduced their movements, but began increasing their movements again around the third weekend in March. The difference in movements was not as stark for metro areas with low income disparities, which were also less likely to have shelter-in-place mandates.

Regardless of individual income, all residents of these privileged neighborhoods benefit from a kind of “social herd immunity” against the virus, while all residents of disadvantaged neighborhoods are at greater risk. Alang posed the scenario: If you shop at a grocery store where everyone is exposed because there’s an essential worker in every single house, that increases your exposure. But if you work in a neighborhood where everyone can work from home, then that reduces your exposure, she said.

Some people who become infected with COVID-19 develop mild flulike symptoms between five and 14 days of getting infected with the virus. While much is still unknown about COVID-19, patients with compromised immune systems and underlying comorbidities, like lung disease and heart conditions, seem to be at greater risk of experiencing organ failure and losing their ability to breathe without the help of a ventilator.

Residential segregation also creates conditions that make people in Black and Latinx neighborhoods more likely to develop severe manifestations of the disease.

Segregated neighborhoods are generally exposed to chronic stressors. Discriminatory policing and ICE raids, injustices in schools and the educational system, housing and insecurity, and housing inequities all take a toll on residents’ cardiovascular, metabolic, and immune systems.

“The stress itself affects the body system, that affects the immune system, that wears and tears your immune system and body organs,” Alang said.

“So when COVID hits, the impact becomes more severe,” she said.

Black and Latinx people are also more likely to live near sources of pollution, like freeways, heavy industry, or waste disposal sites. The Environmental Protection Agency found in a 2018 study that Black residents face the highest impact of particulate air emissions—their exposure is 54 percent higher compared to the overall population. Nonwhite communities have a 28 percent higher exposure, and communities living in poverty face a 35 percent higher exposure.

The disproportionate exposure to pollution in Black and Latinx communities is linked to higher asthma rates among children. Emerging evidence shows that people living in more polluted areas are more likely to die from COVID-19. The study found an increase of 1 microgram per cubic meter of fine particulate matter was associated with an 8 percent increase in COVID-19 death rate.

Arrianna Planey, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign who studies health and medical geography, says it is critical that we understand “the relationship between racial segregation and environmental pollution as being structured overall by structural racism.” Companies have, for example, purposefully targeted low-income communities of color for pollution-generating facilities.

An analysis by The Guardian found that polluted areas of the United States are among those hit hardest by COVID-19. Those areas include neighborhoods in Los Angeles, one of the cities with the worst air quality in the country, and the Navajo nation.

Some of the communities named in The Guardian’s analysis lack access to clean water needed for frequent hand washing, one of the recommendations for preventing spread of COVID-19. Alang pointed out that the American Community Survey data shows Native American people are 19 times more likely to lack complete indoor plumbing, defined as running water, shower or bath, tap, and flush toilet, while Black and Latinx people lack plumbing at nearly twice the rate of their white counterparts.

Experts say that, going forward, we need to think proactively about the way structured inequalities like residential segregation have given rise to the emerging racial disparities in COVID-19.

Contextualizing the emerging data around COVID-19 disparities is also critical in holding leaders and systems accountable and allocating resources to communities in need, said Yeshimabeit Milner, data scientist and founder of Data 4 Black Lives, who advocates for making data tactical, strategic, and grassroots oriented for Black communities.

Given that COVID-19 could be a seasonal illness, addressing the inequities that enable it to thrive in marginalized communities is critical. “If we continue to refuse to do that, we are going to be here 20 years from now talking about this again,” says Acevedo-Garcia.

Planey also notes that monitoring environmental exposures is critical as well. Under the Trump administration, the Environmental Protection Agency has relaxed regulations on lead, mercury, and pollution monitoring. Without fully understanding what toxins and pollutants people are exposed to on a daily basis, it will be difficult to understand outcomes related to COVID-19. “There are all these environmental exposures that are simply not going to be monitored in a few years if this administration has its way,” says Planey.