Coronavirus Exposes Precarity of Prison Towns

Towns like Homer, Louisiana, have huge prisons, a tiny populace, and few public health resources—a potentially lethal combination as COVID-19 spreads.

This piece is a commentary, part of The Appeal’s collection of opinion and analysis.

The COVID-19 crisis is devastating American jails and prisons, which are quickly becoming the epicenter of the pandemic. In Louisiana, which has a reported infection rate of about 4.84 per 1,000 people—over twice the rate for the entire country—a new wave of infections is flooding the state’s prisons.

One federal prison in Louisiana has already drawn national attention for its poor response to the pandemic. At least seven incarcerated people died after the coronavirus spread through FCI Oakdale, a low-security facility 100 miles west of Baton Rouge. Fifty-two other prisoners and staff there had tested positive as of Friday. The federal Bureau of Prisons announced on April 1 that all federal prisoners would be locked in their cells for two weeks in an effort to slow the spread of the virus.

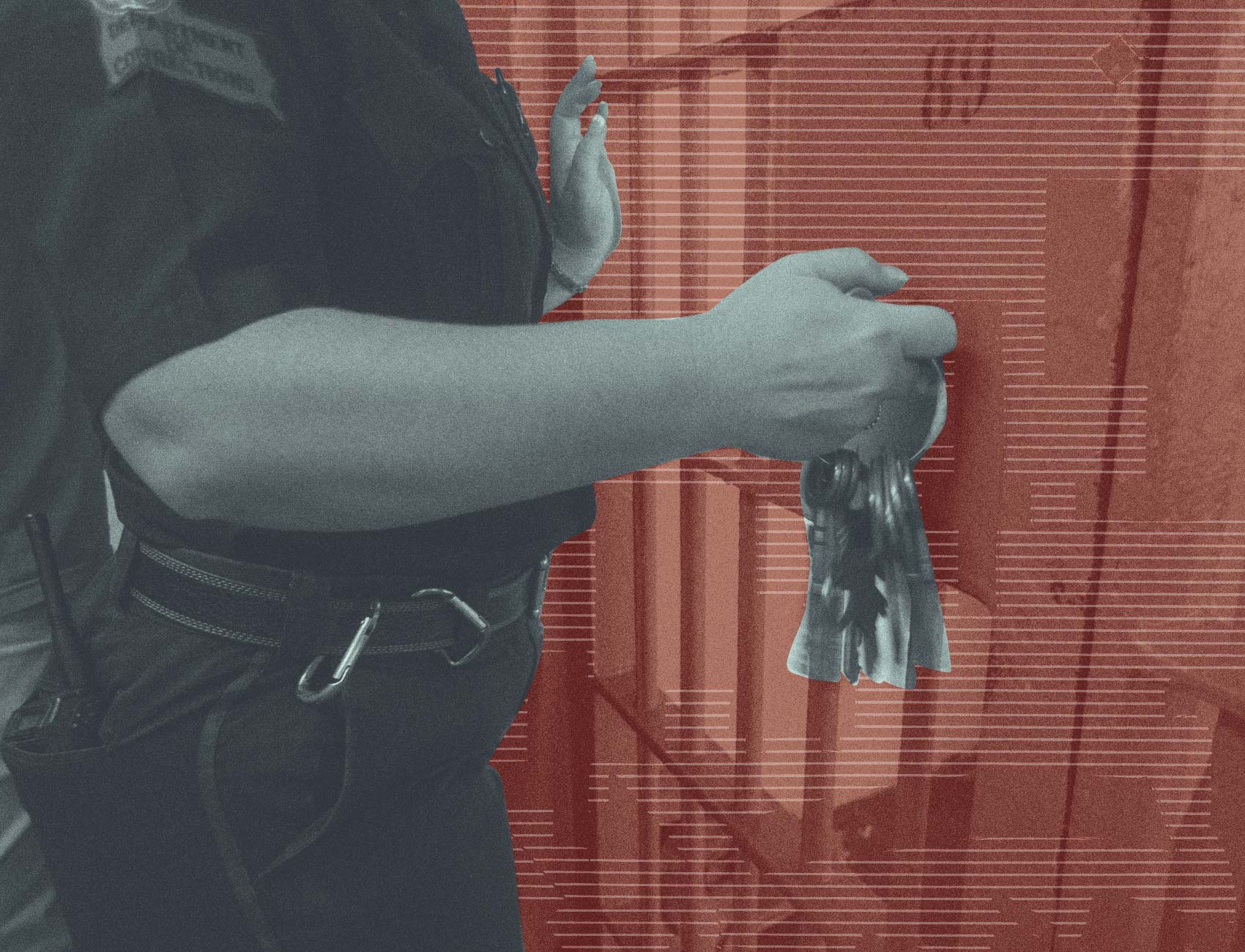

The Louisiana Department of Corrections (DOC) also reported that 81 incarcerated people across eight state prisons had tested positive for the virus as of Friday; 60 employees had also tested positive, including three workers at the David Wade Correctional Center, 10 miles north of Homer. On Monday, the DOC reported its first COVID-19 related death of an incarcerated person and its second coronavirus death among corrections staff. Also on Monday, the Orleans Parish Sheriff’s Office reported that 56 incarcerated people tested positive for COVID-19 at the New Orleans jail, a substantial increase from the 16 positives reported Friday.

Small towns like Homer are particularly vulnerable to epidemics because rural areas often lack health infrastructure, which is associated with higher mortality rates (or a “rural mortality penalty”) under ordinary circumstances. Prison towns are also vulnerable to infectious diseases because so many of their residents work in prisons, which are not known for their effectiveness in controlling the spread of disease.

Homer has a population of almost 3,000 people; David Wade can officially hold up to 1,244 incarcerated people, and almost 350 people work at the prison. The number of incarcerated people at David Wade represents almost half of Homer’s entire population.

David Wade showed signs of crisis long before COVID-19 struck, and it may be one of the worst-equipped prisons in the U.S. to deal with the coronavirus. The prison has been sued over 200 times since it opened in 1980, and the claims in those suits are staggering: guards sprayed disabled prisoners with bleach, treated mental health complaints as if they were disciplinary infractions, and forced prisoners to bark like dogs in order to receive food. In one instance, guards allegedly placed a man who suffered from schizophrenia in a restraining chair, maced him, and then held him there for several days. He was later found unconscious and pronounced dead at a nearby hospital.

Claiborne Parish, where Homer is located, reported 47 confirmed COVID-19 cases and four deaths as of April 13. The mayor of Homer recently enacted a curfew that will be in effect through April 30.

But small social distancing measures will not stop COVID-19 from spreading through the town. Homer’s medical center only has 47 beds, and it’s unlikely that incarcerated people would actually have access to the facility. Even assuming that the medical center increases its capacity by 50 or 100 percent (as some hospitals are doing in response to COVID-19), its bed count would be insufficient to treat hundreds of corrections officers and their families.

Efforts to mitigate the pandemic in prison towns like Homer should include a focus on broader structural problems: states choose to warehouse marginalized people hundreds of miles away from their communities and support networks. Towns suffering from economic decline sometimes go out of their way to attract prison construction projects, because local governments perceive prisons, jails, and detention centers as sources of steady employment. “There’s no more recession-proof form of economic development,” the former city manager of Sayre, Oklahoma told the New York Times in 2001. ”Nothing’s going to stop crime.”

COVID-19 might complicate that theory: it could render Homer so collectively ill that most residents are unable to work.

On a broader scale, scholars and activists have proposed adapting the Green New Deal policy proposal for towns that rely on incarceration for employment. The Green New Deal would create meaningful and socially beneficial employment for towns destroyed by the decline of industry, and because prisons frequently expose rural communities to environmental toxicity, there’s plenty of overlap.

To ensure that the needs of all communities are met, we must free as many people as possible and work towards a more just and sustainable economy.

Jonathan Ben-Menachem writes about politics and culture, focusing on policing, austerity, and the criminalization of poverty.