Corizon, The Prison Healthcare Giant, Stumbles Again

The company recently lost its contract with Arizona after allegations of serious—and sometimes fatal—medical neglect that have echoes across the country.

By the time Walter Jordan began radiation therapy on July 21, 2017, his skin cancer had already eaten through his skull and spread to his brain, according to a doctor who later reviewed the medical files. Jordan, who was incarcerated in a state prison in Florence, Arizona, had squamous cell cancer, a type of skin cancer that has a more than 90 percent cure rate, wrote the doctor, Todd Wilcox.

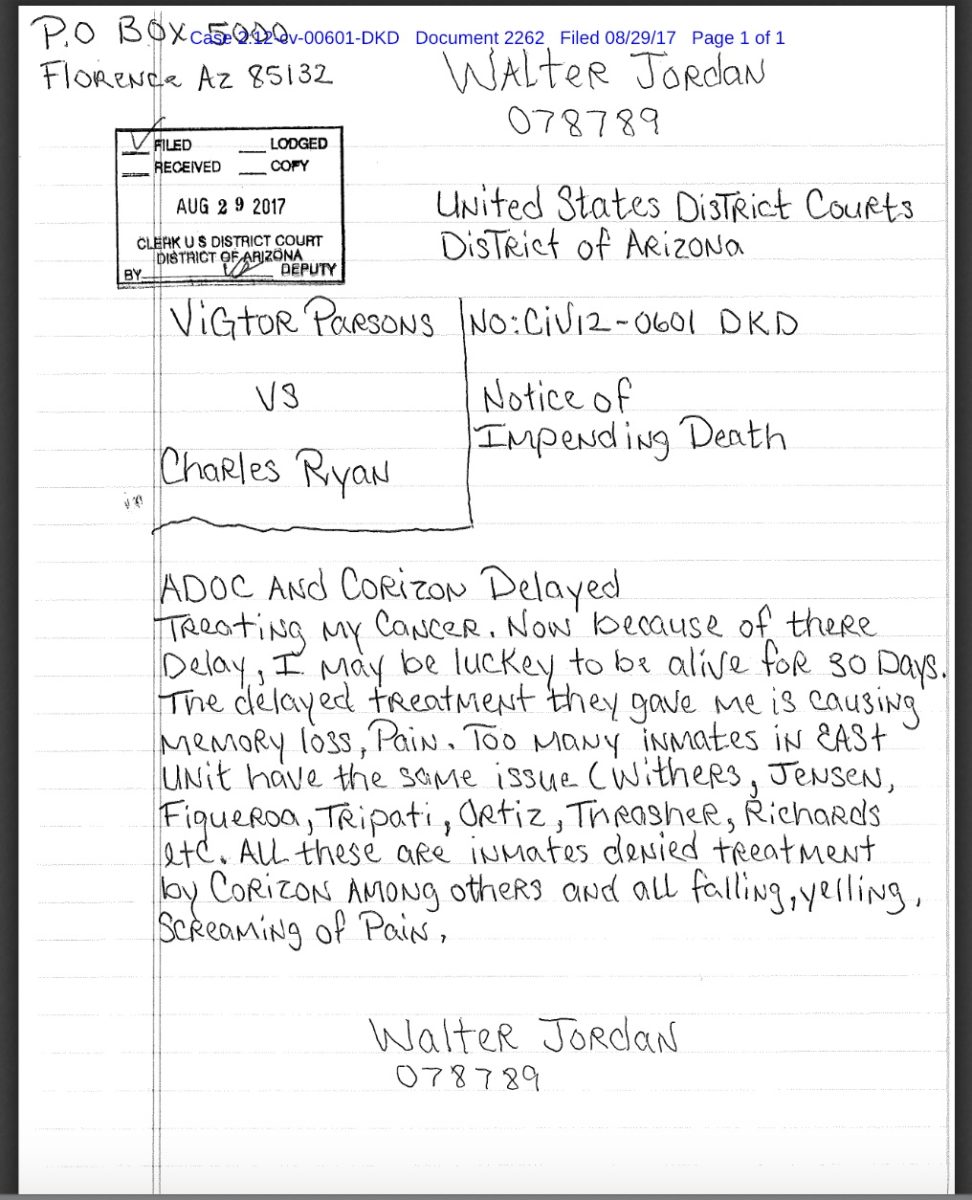

About a week before his death, Jordan wrote to the U.S. District Court. “ADOC [Arizona Department of Corrections] and Corizon delayed treating my cancer. Now because of there delay, I may be luckey to be alive for 30 days.”

For his pain, he was given Tylenol with codeine twice a day, according to Wilcox.

“Mr. Jordan’s case was unfortunate and horrific, and he suffered excruciating needless pain from cancer that was not appropriately managed in the months prior to his death,” Wilcox wrote. “Mr. Jordan may well have survived had he been treated by a competent dermatologist and referred to an oncologist sooner when it was abundantly clear his cancer had progressed beyond the scope of a dermatologist.”

Jordan’s care, advocates say, is part of a pattern of neglect for Corizon Health, which has provided medical care to Arizona’s prisoners for almost six years. Last month, the Arizona Department of Corrections announced that Centurion of Arizona, LLC would be the state’s new prison healthcare contractor starting July 1.

Losing the contract with Arizona is the latest setback for Corizon. The privately held company has been plagued by accusations of deadly medical neglect, as well as questions about its financial practices. For advocates, Corizon illustrates the dangers of an increasingly privatized and opaque correctional system.

In Arizona, the Department of Corrections paid Corizon a “per inmate per day” rate, according to the company’s contract with the state, which amounted to roughly $189 million last year. This arrangement, notes David Fathi, director of the ACLU National Prison Project, created “an almost irresistible incentive to deny care.”

Begging for payment

Arizona’s prison healthcare woes predate Corizon’s arrival. In 2012, the ACLU of Arizona, ACLU National Prison Project, Prison Law Office, and Arizona Center for Disability Law sued the Department of Corrections, which was then providing healthcare internally, for allegedly failing to supply adequate healthcare to the state’s prisoners. The next year, Corizon was awarded a contract with the Department of Corrections, and in 2015, the court approved a settlement between the agency and the plaintiffs that mandated a number of changes, including timely responses to patients’ medical requests and healthcare grievances.

But in June 2018, U.S. Magistrate Judge David Duncan fined the Department of Corrections approximately $1.4 million for not complying with terms of the agreement—$1,000 per violation—finding that, “The Court must place a clear and focused light on what is happening here: the State turned to a private contractor which has been unable to meet the prisoner’s health care needs.”

Throughout 2018, attorneys with the Prison Law Office sent a series of letters to Struck Love Bojanowski & Acedo, the law firm representing the Department of Corrections, pleading for help for people suffering from a variety of ailments, including a man forced to wait four months for a biopsy for basal cell carcinoma, a terminal leukemia patient denied narcotic pain medication, and a man with diabetes who went 48 hours without receiving insulin.

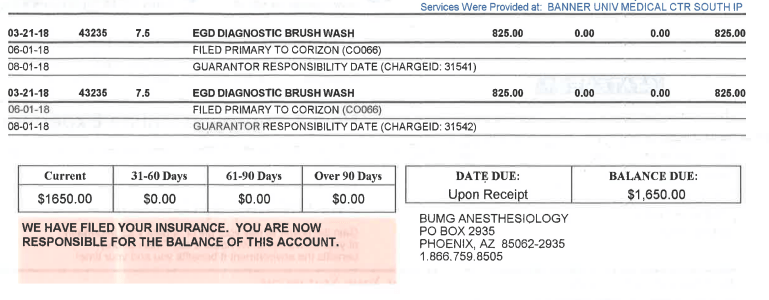

In addition to continued incidents of medical neglect, prisoners have been billed for services that were supposed to be paid for by Corizon, according to Corene Kendrick, an attorney with the Prison Law Office.

“We are also concerned about Corizon’s inability or unwillingness to timely pay its specialty subcontractors prior to and after the transition,” Kendrick wrote in a letter dated Jan. 30 to Struck Love.

In an email to The Appeal, Martha Harbin, Corizon’s director of external relations, said these “are nothing more than billing errors on the part of these providers.”

During the course of their litigation, Kendrick said, the firm also discovered that Florence Hospital at Anthem claimed it was owed more than $1 million in outstanding bills, dating back to February 2016.

“This amount outstanding for our hospital is unacceptable,” Laura L. Slacian, director of patient financial services for New Vision Health, wrote in an email on March 13, 2017, to Shawn Lewis, provider relations representative at Corizon. “I continue to have to constantly follow up and literally beg you for payment of our bills.”

Last April, a similar situation arose in Idaho when the Saint Alphonsus Health System, which encompasses four hospitals, sued Corizon, alleging it was underpaid more than $14 million for its treatment of incarcerated patients. Saint Alphonsus claims that Corizon has been paying Medicaid rates even though the health system has “specifically rejected such proposal on numerous occasions,” according to the complaint.

Corizon said at the time that the Medicaid rate was set by state statute, but the Idaho Supreme Court ruled in January 2018 that the state law does not apply to private correctional providers that contract with the Department of Correction.

Harbin denies there are any financial issues with the company. “I can unequivocally tell you that Corizon Health is financial[ly] healthy,” Harbin said in an email. She noted that the emails concerning Florence Hospital are “from the month before we announced our corporate reorganization.”

That occurred in 2017, when BlueMountain Capital Management, a New York- and London-based hedge fund, became the majority shareholder in Corizon, replacing the Chicago-based private equity firm Beecken Petty O’Keefe & Company, which retains a small stake in Corizon, according to Harbin. Other investors also participated in Corizon’s reorganization in 2017, but when asked to identify them, Harbin declined, saying that they “did not want me to publicly release their names.” The investment group formed in 2017, of which BlueMountain is a member, has one representative on Corizon’s board of directors, Harbin said.

“BlueMountain invested in Corizon because it provided an opportunity to reposition an underperforming business to improve patient care, increase existing standards of care, and enhance business performance,” BlueMountain spokesperson Tom Vogel wrote in an email to The Appeal. “Since BlueMountain’s initial involvement, Corizon has reduced its long-term debt by more than half, obtained additional capital, reconstituted its board of directors and upgraded its management to transform its practices, procedures, and healthcare delivery.”

The company’s healthcare workers have about five million patient encounters a year and a daily patient population of about 180,000 people, according to Harbin.

“People out there are working very hard and using their training and trying to do the best job that they can,” she said. “These are passionate, caring people who choose to be working in this environment and with these patients.”

Corizon has 31 contracts in 17 states, according to Harbin, who declined to name the clients. These include correctional agencies, cities, and counties. In 2015, previous Corizon CEO Woodrow Myers told the Marshall Project that the company had 114 contracts in 27 states.

Asked about the decline, Harbin said, “It’s just kind of the nature of government contracting. Contracts come and go. … I would certainly not say it’s a reflection on our care.”

‘Cash flow’ issues

Yet, questions about Corizon’s care and finances have swirled for years. Tyler Tabor, 25, of Johnstown, Colorado, was arrested on May 14, 2015, on warrants for a traffic offense and two misdemeanors. Unable to pay the $300 bond, Tabor was held in the Adams County Detention Facility.

When he arrived, he told the medical staff that he was a heroin user and had used that morning, according to an investigatory memo prepared by the district attorney’s office for Adams and Broomfield counties. Over the next few days, he vomited repeatedly, was unable to eat, and struggled to stand, eventually needing a wheelchair to go to the infirmary, according to the memo. He died on May 17, three days after his arrival.

In 2016, Tabor’s family sued Corizon, alleging that his death could have been prevented if he had been given an IV. On June 4, 2018, Corizon and the Tabors agreed to settle the case for $3.7 million, which was to be paid once the settlement was approved by the probate court, according to the settlement agreement.

On Oct. 30, 2018, the probate court approved the settlement, but on Nov. 2, Corizon paid just $1 million, according to a motion filed on behalf of the Tabors. Corizon’s payment was “followed by a statement from counsel for Corizon that a ‘cash flow’ problem existed with Corizon,” and a request to pay the rest of the money, with interest, in installments, according to the motion.

I feel like I am very close to death. Can’t hear, seeing lights, hearing voices. Please help me.”

Madaline Pitkin prisoner who died in 2014

According to the Tabors’ attorney, David Lane, Corizon has made two of the three payments, with the final payment scheduled for Feb. 19.

“There is nothing unique or unusual in defendants in a large settlement [structuring] payments to protect cash flow,” Harbin emailed The Appeal.

In Oregon, a year before Tabor’s death, 26-year-old Madaline Pitkin died under similar circumstances in a Washington County jail. She was denied medical help as she suffered from heroin withdrawal.

“I feel like I am very close to death. Can’t hear, seeing lights, hearing voices. Please help me,” she wrote in one of several urgent requests for medical help. She died about a week after arriving at the jail. In December, a federal court approved a $10 million settlement between Corizon and Pitkin’s family.

Profiting off prison

Advocates accuse the correctional services industry, which is often propped up by private equity and hedge funds, of prioritizing profits over care for incarcerated patients.

“What you’re seeing is a growingly complex field in terms of people who are invested in mass incarceration,” said Tiera Rainey, a program coordinator with the American Friends Service Committee-Arizona, a prisoner advocacy organization. “They don’t just invest out of benevolence. They invest money to make profit.”

When asked what profits have been generated from BlueMountain’s investment in Corizon, Vogel emailed a statement: “BlueMountain Capital Management is a diversified alternative asset manager that invests in both public and private markets with a range of time horizons. The firm’s investment in Corizon Health is similar to a typical private equity investment because it has been structured as a multi-year investment with the goal of improving Corizon’s operations. Thus, it would be premature to expect a return on investment at this early stage.”

Private equity firms are invested in companies that provide not only healthcare, but commissary, communications (phone and email), probation services, and food to more than two million incarcerated people in prisons and jails throughout the country, according to a report published in December 2018 by the Private Equity Stakeholder Project, which tracks the financial sector’s involvement in a number of industries.

The American Federation of Teachers, a union representing more than a million members, released a report this month detailing the role of private equity in correctional services, including Corizon and BlueMountain. (This reporter is a member of the union’s Rutgers University chapter.)

Ethical and moral issues are what create the risk to investors.

Elizabeth Parisian American Federation of Teachers

“We think these are risky investments,” said Elizabeth Parisian, who wrote the report. “Ethical and moral issues are what create the risk to investors.”

The report calls on public employee pension funds to examine their investments in these types of companies and, Parisian said, conduct a “due diligence analysis.” These funds can consider a number of actions, including divestment or they can engage with private equity firms to express concerns about investments in correctional services, Parisian said.

Corporations that contract with the government are often not subject to open meeting laws or freedom of information laws, Fathi of the ACLU National Prison Project told The Appeal. But those that are publicly traded must share certain information with the Securities and Exchange Commission, such as governance structure and audited financial statements. This information is made available to the public in an online database. Privately held companies like Corizon, on the other hand, generally have far fewer disclosure requirements.

“There’s even less transparency,” Fathi said.

And that means even less is known about the “changing face of who is profiting off of mass incarceration,” Rainey said.

“If you hear the stories of these families and the pain that they have suffered, [BlueMountain] should be ashamed they’re investing,” said Rainey. “Every dollar you’re making off of that investment is coming from human suffering.”