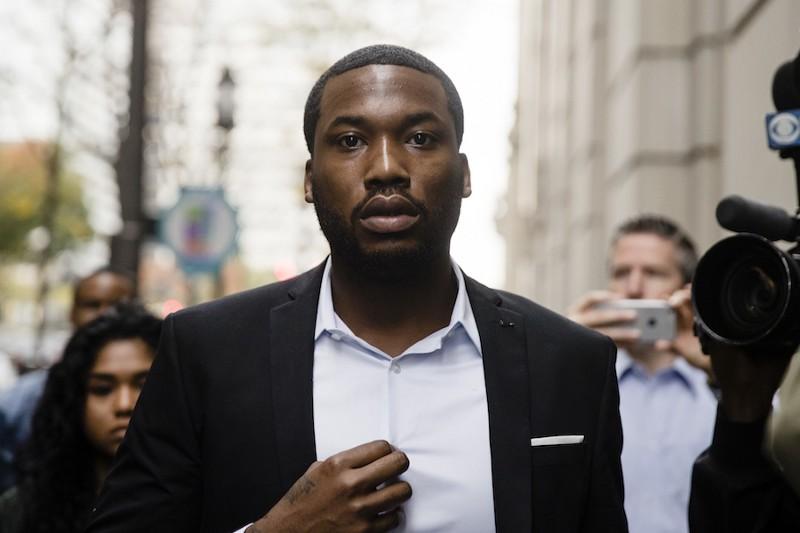

Commentary: Meek Mill’s Sentence Reveals Problems with Pennsylvania’s Extreme Use of Court Supervision

Hip-hop artist Meek Mill was named one of the 100 most influential Philadelphians by Philadelphia Magazine. However, rather than his music, his recent prison sentence is what has garnered the spotlight, helping to focus attention on the problems of our criminal justice system, specifically the issue of court supervision in Pennsylvania and its impact on […]

Hip-hop artist Meek Mill was named one of the 100 most influential Philadelphians by Philadelphia Magazine. However, rather than his music, his recent prison sentence is what has garnered the spotlight, helping to focus attention on the problems of our criminal justice system, specifically the issue of court supervision in Pennsylvania and its impact on mass incarceration.

This past week, on November 6, Judge Genece E. Brinkley sentenced Mill, 30, to two to four years in state prison for a probation violation. Over ten years ago, an 18-year-old Mill was arrested for drug and gun possession. In 2009, Judge Brinkley sentenced Mill — who was then known by his given name Robert Rahmeek Williams — to 11 ½ to 23 months in prison, followed by eight years of probation. Since that time, the judge has overseen his case.

Many people are outraged over the injustice of Mill’s lengthy sentence, and they should be. Criminal justice advocate Jay-Z, whose Roc Nation recording company signed the Philadelphia native, took to Facebook and called the sentence “unjust and heavy handed,” pledging to “always stand by and support Meek Mill, both as he attempts to right this wrongful sentence and then in returning to his musical career.” Said CNN contributor Van Jones, “It is absolutely outrageous. It is one of the worst things I’ve ever seen. I’ve never heard of a case where a brother stands before a judge; the prosecutor says, do not put this brother in jail; the probation office says do not put this brother in jail; And, for some reason, the judge says I’m going to put him in jail any way.”

And a petition on Change.org in support of Mill is closing in on 200,000 signatures.

The public outcry over this case underscores how people are sent to prison over technical violations versus direct violations. A probationer incurs a direct violation if he or she is convicted of a new crime while on probation. A person who has failed to comply with the terms of their probation — but who has not committed a new crime — receives a technical violation. Pennsylvania law permits a judge to incarcerate a defendant only if he or she already committed, or is likely to commit, a new crime. Even more problematic, that same statute allows a judge to impose prison time if “such a sentence is essential to vindicate the authority of the court” — which means the law allows a court to incarcerate someone merely if the judge feels disrespected.

What did Mill do to cause the judge to send him to prison? This past year, he was arrested for a fight in the St. Louis airport — charges were dropped — and took a dismissal deal for reckless driving and “popping a wheelie” on his dirt bike.

Meanwhile, 4.65 million adults in the U.S. are on probation or parole, or 1 in 53 adults. Pennsylvania — which has the highest incarceration rate in the Northeast — has the fourth highest number of people under government supervision, long after they committed their crimes, with 280,000 people as of 2015, and one-third of all prison beds in Pennsylvania are occupied by people who violated the terms of their probation or parole. This comes at great expense to Pennsylvania’s taxpayers, diverting precious resources from education and social services.

Meek Mill has become the face of probation and parole and the excesses of a system that ensnares so many without celebrity status. When the law allows judges to incarcerate people under their supervision solely because of a technical violation — when they committed no new crime and pose no threat whatsoever — we have a problem.