Political Report

Colorado Governor Opposed Banning ICE Contracts. But They May Already Violate State Law.

A new Colorado law curbs ICE’s reach, but it was weakened during the legislative process and stripped of its prohibition against ICE contracts.

A new Colorado law curbs ICE’s reach, but it was weakened during the legislative process and stripped of its prohibition against ICE contracts.

This article is part of a series on 287(g) contracts with ICE in states.

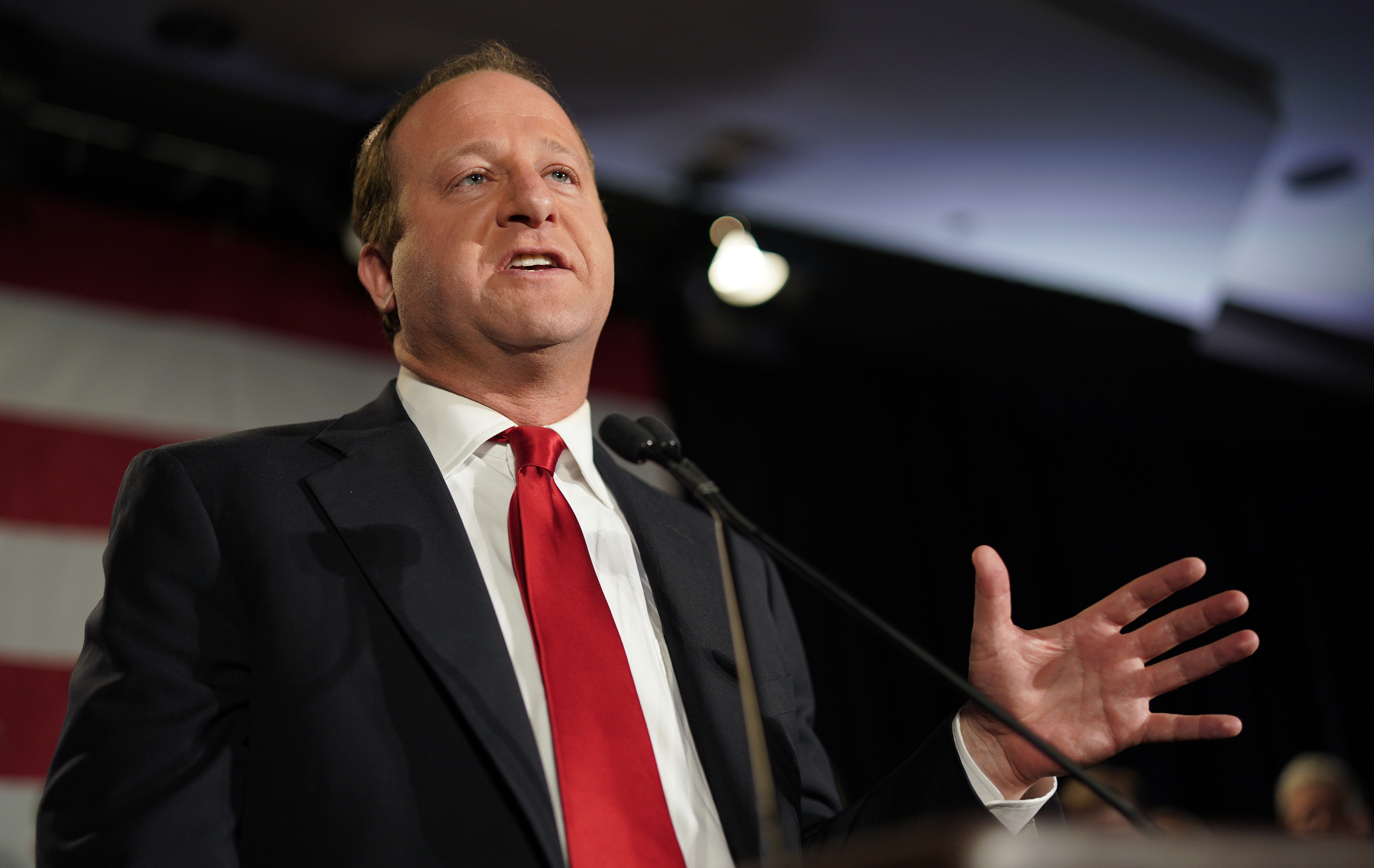

Opposition to ICE has risen on the left during the Trump administration. But a Colorado bill to curtail the agency’s reach was considerably weakened after Democratic Governor Jared Polis objected to restrictions it imposed on local cooperation with federal immigration authorities.

His office warned in April that he would veto House Bill 1124 unless it was stripped of some of its most important provisions, including a ban on counties joining ICE’s prized 287(g) program. As of this week, only 86 counties nationwide (including Colorado’s Teller County) are part of this program, which deputizes local officers to act like federal immigration agents.

The bill’s sponsors dropped some provisions in response, including the one that directly targeted 287(g). This left them with “a shell of what they once hoped to advance this legislative session,” Alex Burness wrote in the Colorado Independent.

Polis signed the bill’s narrowed version, which restricts cooperation on the part of probation departments and bars law enforcement from honoring ICE requests that they detain people beyond their scheduled release, in May.

“We were faced with a choice, either run a bill that the governor would sign or that the governor would veto,” Democratic Senator Julie Gonzales, one of the sponsors, told me. She added that she had been “surprised” by Polis’s “really staunch opposition to certain aspects of the original version” of HB 1124, as well as to another reform that derailed earlier in the year.

But immigrants’ rights advocates also argue that 287(g) has been invalid under Colorado law all along, and that the final version of HB 1124 does contain a clause that reaffirms this.

What was removed from HB 1124

One provision that the governor opposed would have barred ICE from entering jails without a warrant. It was removed from HB 1124.

Another section would have prohibited local authorities from entering contracts to help enforce federal immigration law. This would have applied to the 287(g) program. The Political Report wrote on this aspect of HB 1124 in February, before the bill was amended.

Critics argue that 287(g), which authorizes local officers to research the status of people held in jail and to arrest suspected undocumented immigrants, distorts the purpose of local agencies and harms public safety. “When local law enforcement gets involved with immigration enforcement, it erodes trust and it creates fear in the local community,” Angela Chan, the policy director and a senior staff attorney at Asian Americans Advancing Justice – Asian Law Caucus, told me.

Chan helped draft the law that California adopted in 2017 to limit cooperation with ICE. This law forced Orange County to terminate its 287(g) contract. Illinois is now considering similar legislation, and the original version of Colorado’s HB 1124 would have had a similar effect.

Polis’s office did not reply to a request for comment on the governor’s position.

His staff told the Colorado Independent in April that he was committed to protecting counties’ local control. Chan described that position as ironic because by joining 287(g) a “local law enforcement agency is deciding that rather than doing their job they’re going to take on federal responsibility.”

The governor’s office also voiced a separate concern in April that “blanket prohibitions” would prevent “human and drug trafficking task forces that are important to public safety.” These are task forces that are formed to investigate criminal activities, though they often result in collateral arrests over civil immigration violations.

Despite the law’s narrowing, Colorado advocates also contend that the removed section was not necessary to ban 287(g).

“The ACLU believes that these agreements violate existing state law and will explore that avenue going forward,” Denise Maes, public policy director of the ACLU of Colorado, told me. Brendan Greene, campaigns director of the Colorado Immigrants Rights Coalition (CIRC), agreed.

Their argument is that Colorado sheriffs have only those powers granted by state law, which makes no mention of sheriffs partaking in civil immigration law. They point to a 2018 court ruling in which a judge found that sheriffs had no “statutory grant of authority” to “enforce civil immigration law or even to cooperate with its enforcement.” Yet in a different case, another Colorado judge took the inverse approach last year. What she found decisive is that Colorado lacks “a statute prohibiting law enforcement from cooperating” with federal agents.

The final version of HB 1124 contains a clause affirming that sheriffs only possess explicitly enumerated powers: “The authority of law enforcement is limited to the express authority granted in state law.”

State Representative Adrienne Benavidez, a Democrat who sponsored HB 1124, told me this clause “may not stop somebody” from joining 287(g), but that it represents “additional legislative support to a civil action in court against local law enforcement that did that.” She granted that this “would not be automatic” since lawmakers “had to remove” the “original language” after “the governor didn’t feel comfortable,” but added “there are grounds to challenge it in court.” Greene said similarly that “this is something that may have to be decided by the courts,” but that CCIRC was “confident” that courts would clarify that sheriffs cannot execute 287(g) contracts.

Polis’s office did not reply to a request for comment about whether he believes that this clause, in the law he signed, could serve to challenge 287(g) contracts. The Teller County Sheriff’s office also did not respond to a request for comment about the legality of its 287(g) agreement.

What HB 1124 does contain

As adopted, HB 1124 curbs ICE’s reach in three ways. First, it restricts communication between ICE and probation officers, who until now could share information with federal agents who lacked a warrant. Second, it bars local law enforcement from detaining people beyond their schedule release because of a detainer request by ICE; two Colorado sheriffs began honoring these detainers in 2017 and 2018, prompting a legal battle.

Third, it requires that people held at the county jail be advised that they do not have to talk to ICE agents, and that their answers could be used against them in removal proceedings if they do. “We really think it’s going to help clarify who’s who and make sure that people can understand their constitutional rights before they consent to give that type of interview,” Greene said.

Gonzales, the state senator, warned that “there’s still a lot of work to be done on that front to make sure that jails are getting the information right and in people’s preferred language, and that they then have access to pro bono attorneys.” She also said that the legislature must do more to “draw a bright line” and tell ICE to “stop using our local law enforcement as a force multiplier for your deportation machine.”

Earlier this year, Gonzales sponsored another bill that the legislature adopted and Polis signed into law. This reform reduces the maximum sentence associated with some misdemeanors and municipal violations from 365 to 364 days, a small change that actually has the big implication of shielding noncitizens convicted of those offenses from deportation.

Other advocates vowed to demand further protections as well.

“HB 1124 is a simple and important step,” Maes said. “But politicians and elected officials need to know that we plan to push the envelope” so that “our immigrant families, friends and neighbors no longer need [to] live in the shadows.”