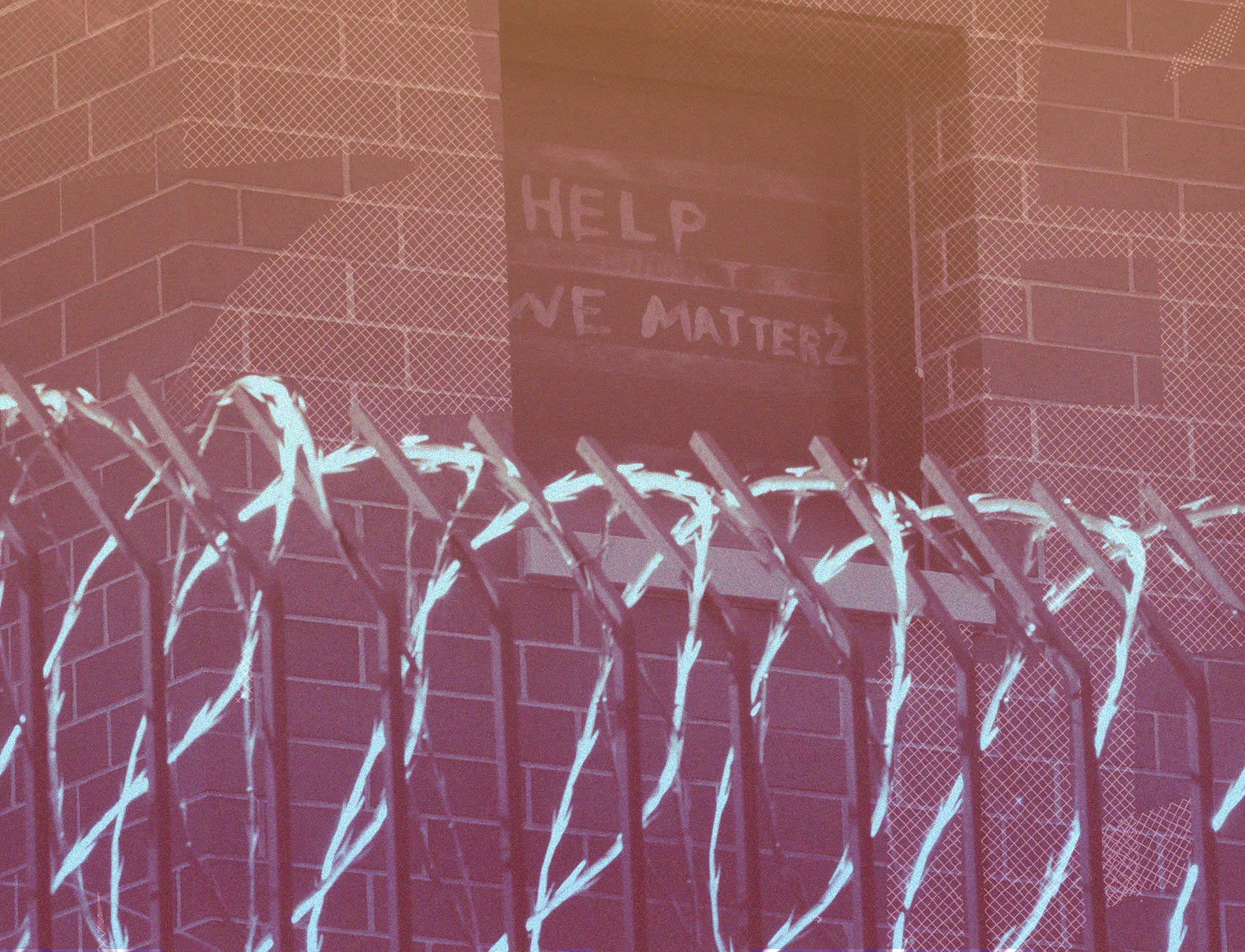

Amid One Of The Nation’s Worst Coronavirus Outbreaks, A Shortage Of Ankle Monitors Kept Some People In Jail

Advocates question why Chicago judges continued to order people to home detention instead of releasing them on their own recognizance.

At least 10 people were held for several days in Chicago’s Cook County Jail, one of the country’s hot spots for COVID-19 infections, because the city ran out of ankle monitors.

As of Sunday, 542 people in the jail have tested positive for COVID-19, and seven detainees and three sheriff’s office employees have died from the disease. Those numbers are most likely low, given that the jail has tested only 42 percent of current detainees.

Cook County expanded its already large electronic monitoring program and moved people to home confinement as part of an effort to reduce the jail population to allow for social distancing. The jail population fell from 5,604 detainees on March 1 to 4,281 as of Friday. There were also 3,205 people on ankle monitors through the program, according to Sheriff Tom Dart’s office, up from 2,417 on March 1 before COVID-19.

But the county wasn’t prepared for this surge in home confinement. Due to supply chain issues, there were not enough monitors to meet the heightened demand. Allison Peters, assistant press secretary in the Cook County sheriff’s office, told The Appeal in an email that on May 7, there were 10 detainees who could not be processed for release due to the equipment shortage. The office received the equipment on May 9 and they were processed the same night, she said.

Before their release, Sharlyn Grace, executive director of the Chicago Community Bond Fund, called on county judges to stop putting lives at risk by needlessly ordering people onto electronic monitors when the county didn’t have any. Her organization demanded the release of anyone incarcerated at the Cook County Jail on May 7 because of lack of equipment.

“By ordering someone to electronic monitoring, it’s considered a release decision,” she said. “But if there are no ankle shackles available, the person is going to remain in jail. It’s a pretend release decision with a de facto result of incarceration but without the court having to meet any of the standards required to justify someone’s pretrial incarceration, and that’s a violation of due process.”

Grace questioned why judges continued to order people to home detention instead of releasing them on their own recognizance, trusting them to show up for their court appearances without any conditions of release.

“It’s very concerning for all of us who want there to be a high standard before the government takes away our freedom,” she said.

Though judges ultimately determine whether someone will be ordered onto electronic monitoring, criminal justice reform advocates also blamed the state’s attorney’s office. According to data compiled by the Chicago Appleseed Fund for Justice, State’s Attorney Kim Foxx’s office argued against release in 80 percent of the 2,366 motions for bond reduction argued between March 23 and April 22. From April 22 through May 6, the office’s opposition rate was between 70 and 80 percent. Foxx’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

Sarah Staudt, senior policy analyst and staff attorney at Chicago Appleseed, said that when the state’s attorney’s office opposed a bond motion, judges often ordered conditional release.

“They granted a bond reduction to let someone out of custody but they mandated that that person be on electronic monitoring, which is a part of the reason that electronic monitoring is at its highest level,” she said.

While more people are being ordered to electronic monitoring, the thousands of people who already had ankle monitors before the pandemic are not getting off them because of court closures, compounding the shortage, Staudt said.

“Normally you have a court date every 30 days,” she explained. “If something changes about your cases or if you’ve been doing well on electronic monitoring or need special movement, you have a court date to do that. But people aren’t having court dates at all.”

Currently, Cook County’s population on electronic monitoring includes 30 people charged with a cannabis felony, 139 people charged with driving with a revoked or suspended license, 11 charged with misdemeanor theft, 180 with felony theft, 17 with criminal damage to property, and 150 with a DUI. Staudt said that many of these crimes should not necessitate electronic monitoring, especially during a time when the state is already under stay-at-home orders because of the pandemic and crime rates have significantly dropped.

Criminal justice reform advocates who oppose the use of pretrial electronic monitoring point to research showing that the vast majority of people will show up to court with just a reminder text or call.

“There’s very little reason to believe that EM is effective, which means that nobody needs to be on the monitor, especially people who have low-level cases we would not normally associate with being placed on electronic monitoring,” Staudt said.

Ankle monitors also impose burdens on people’s personal and professional lives. Dart’s electronic monitoring program requires participants to be on house arrest for 24 hours a day, making it the strictest possible form of monitoring. The office typically requires 72 hours’ advance notice to request a motion, and people are often denied movement to go to the grocery store or do other essential tasks.

“It’s a very severe restriction on people’s liberty while they’re awaiting trial,” Grace said. “It prevents people from accessing healthcare or other resources, going to the grocery store, taking care of the business of their daily lives, which is particularly concerning during this public health crisis.”

For that reason, Staudt said she takes issue with the idea that Cook County is facing a shortage of ankle monitors.

“The problem isn’t that we don’t have enough bands,” Staudt said. “We have too many people.”

Sheriff Dart has also questioned the expansion of electronic monitoring and the lack of resources his office has to meet the growing population. In a letter to officials in Cook County’s legal system on May 7, he said that he has “long called for criminal justice stakeholders to confront the rapid growth of the EM population, including the evolving makeup of criminal charges of that population since Cook County enacted bond reform.”

Last month, Dart’s office was hit with a federal lawsuit by civil rights groups seeking the mass release of medically vulnerable people from the jail during the pandemic. A federal judge ordered Dart to take various steps to prevent the spread of COVID-19 in the jail, including more testing and keeping incarcerated people apart from one another.

Dart appealed and accused civil rights groups of misusing the federal courts to push for decarceration, but a court ruled Friday that the order has to go into effect pending his appeal.

Criminal justice reform advocates remain adamant that Dart and other actors in Chicago’s legal system need to move quickly to release people, given how dangerous jail conditions are right now.

“We do not have the death sentence in Illinois,” Grace said. “We certainly don’t have it for people who are awaiting trial.”