|

Louisiana: Cooperation with ICE looms large in sheriff elections

The Ascension Parish sheriff’s department detained a U.S. citizen as part of an immigration hold for four days despite a court order that he be released, according to a lawsuit by the ACLU of Louisiana. The ACLU alleges that this is part of a systematic policy to target Latinx individuals. Sheriff Bobby Webre, who was not yet in office during these specific events, told The Advocate that he would mount a “rigorous defense” of his department.

Moses Black Jr., however, takes issue with current practices. He is challenging Webre in the Oct. 12 sheriff’s election.

“The ACLU is doing the right thing bringing this to light,” he told the Appeal: Political Report. Local authorities are participating in a nationwide “all-out war on Hispanics,” he said, because “they can get away with it.” Webre’s office did not answer a request for comment on the ACLU’s allegations; Byron Hill, the third candidate in the race, also did not respond.

Louisiana will hold 63 elections for sheriff this fall. These could impact ICE’s reach, as well as the scale of immigration enforcement and detention in the state.

Sheriffs nationwide have the authority to enter into various partnerships with ICE, both formal and informal. In Louisiana, many have taken full advantage over the past year to help the federal agency identify or incarcerate undocumented immigrants.

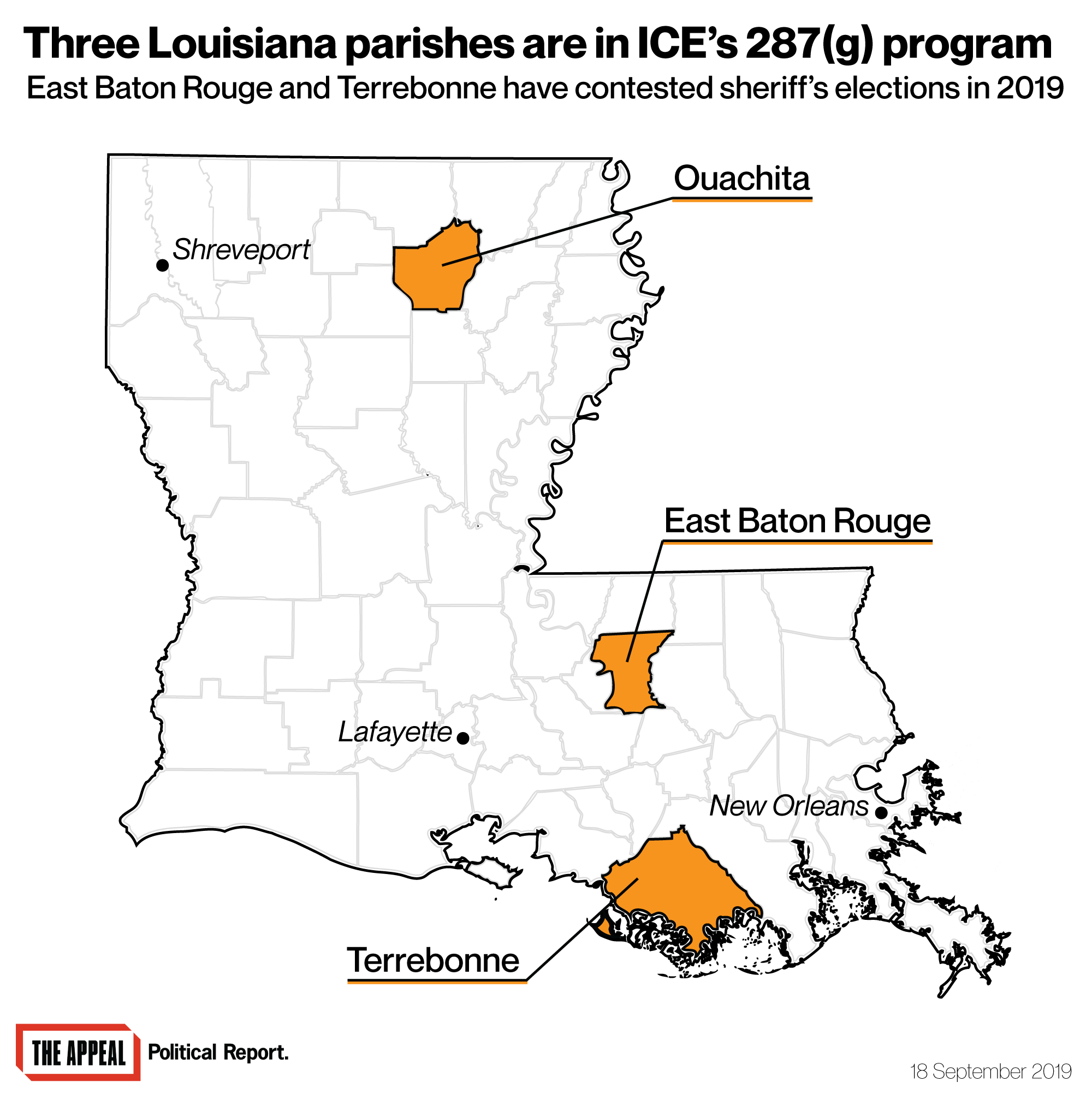

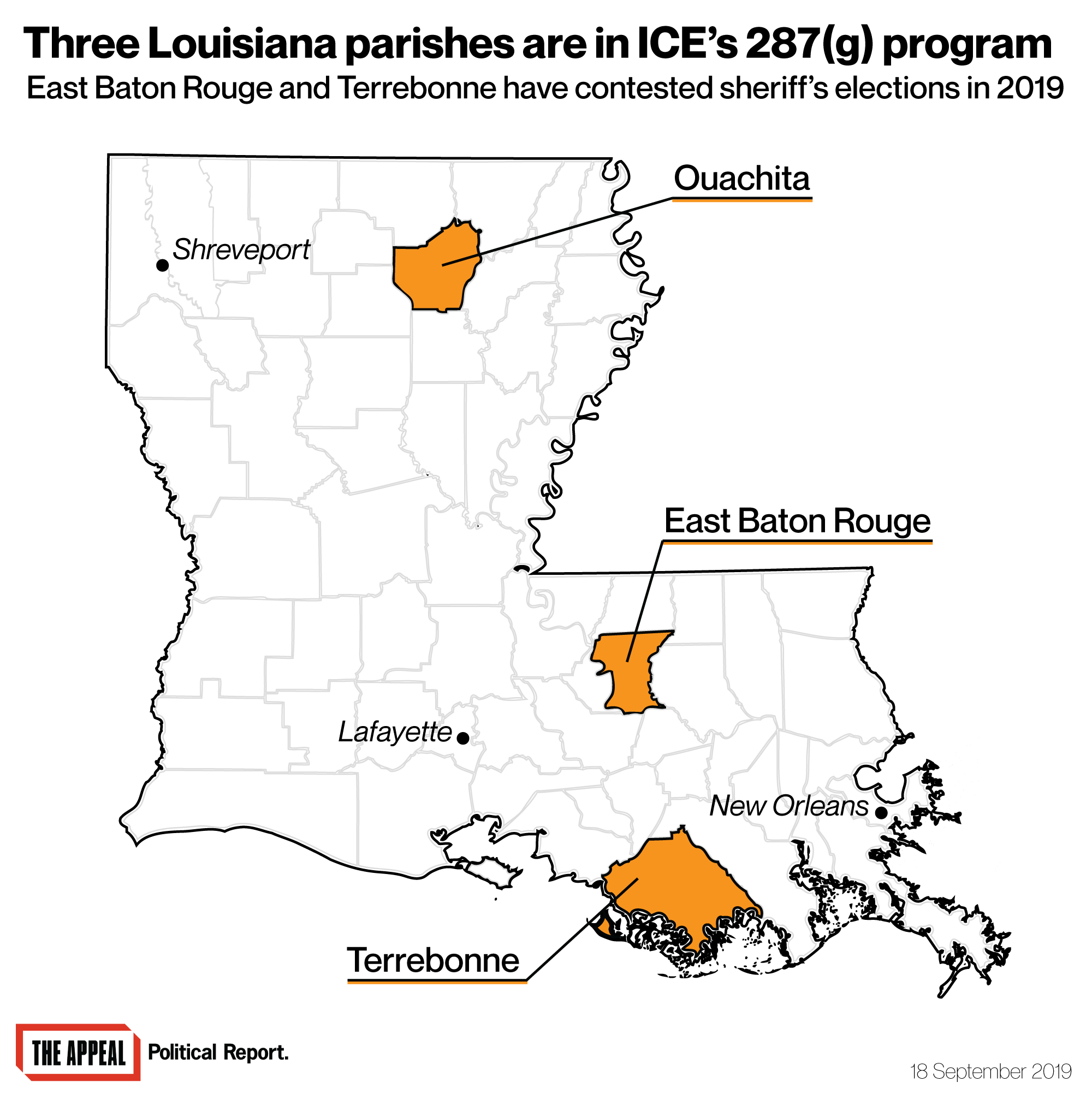

As Louisiana’s incarceration rate plunged in recent years, local agencies have rapidly entered in new contracts to rent now-vacant jail space to ICE, considerably expanding the federal agency’s capacity to detain immigrants. In addition, three sheriff’s departments have now joined ICE’s 287(g) program (two of them this year), which authorizes local deputies to act as federal immigration agents within parish jails.

“This is a crisis happening in our own backyards, betraying the state’s commitment to decarceration and exposing thousands of immigrants and asylum seekers to brutal and dehumanizing conditions,” Alanah Odoms Hebert, executive director of the ACLU of Louisiana, told the Political Report. People detained by ICE in the state are held in poor conditions, investigations have found.

Black, the sheriff candidate, faults the underlying racial pattern in this resilience of incarceration, and links amplified immigration enforcement to the criminal legal system’s disparate impact on African Americans. “I see Blacks who go to jail for lower offenses, and what they’re trying to do to Hispanics who come to the United States to make a better life for themselves and their families—I see that right now the government is trying to prevent that,” he said. “They’re trying to send Hispanics to Mexico or Honduras and put Black men in jail. The United States is made for everybody.”

“It’s a business for them,” he added. ICE pays counties more money to detain an immigrant than the state pays them to incarcerate someone with a criminal conviction.

The sheriff’s elections this year offer a platform for immigrants’ rights advocates to call these policies into question. There is an election in every parish except Orleans (New Orleans), which is on a different schedule.

“These sheriffs absolutely need to answer to voters about their role in this crisis that diverts resources away from other public safety priorities and makes everyone less safe,” Odoms Hebert said, calling on candidates to curb cooperation with ICE and specifically to commit to ending 287(g) partnerships.

Nowhere is this issue more at stake than in East Baton Rouge, the state’s most populous parish. The sheriff who signed a 287(g) contract is running for re-election, and his two challengers told the Political Report that they oppose the partnership.

Click here for the rest of the Political Report’s primer on the 2019 sheriff’s races in Louisiana and ICE cooperation, including in East Baton Rouge.

|