California Has a Chance to Repeal a Building Block of Lengthy Prison Sentences

Senate Bill 136 would repeal one of California’s most frequently used sentence enhancements, which gives judges the discretion to add a year to a felony sentence for every prior felony prison or jail term.

Spotlights like this one provide original commentary and analysis on pressing criminal justice issues of the day. You can read them each day in our newsletter, The Daily Appeal.

The “tough on crime” era in California, as across the nation, included reaching repeatedly for draconian sentencing laws. Consequences have been evident in the state’s prison overcrowding crisis, which the United States Supreme Court found caused “needless suffering and death”; its sentencing laws, which still include over a hundred sentence enhancements; and in communities where generations of children and parents have suffered lasting separation.

But California, where crime is at historical lows, has been the site of significant criminal justice reforms in recent years. These have included efforts to roll back or modify some of the sentence enhancements that have contributed to lengthy sentences. Nearly 80 percent of people held in California state prisons have been affected by sentence enhancement. Over a quarter had three or more.

The most notorious of California’s sentencing enhancements is the “Three Strikes and You’re Out” law, passed by voters in 1994, which imposed a life sentence for almost any conviction, if a person had at least two prior convictions for crimes defined as serious or violent. Proposition 36, enacted by voters 18 years later, did away with the harshest consequences of the law, when it eliminated life sentences for non-serious, nonviolent crimes and established a procedure for people sentenced to life in prison to petition in court for a reduced sentence.

Right now, a bill making its way through the state legislature would do away with one of the most commonly used enhancements—a year that can be added to any felony sentence for any previous felony conviction that resulted in a sentence of prison or jail time, regardless of the length or the nature of the prior or current convictions. Senate Bill 136 passed the Senate this session. Emily Harris, interim policy manager with the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights, told the Daily Appeal that it must move out of the Assembly Appropriations Committee by Friday in order to have a chance of becoming law this year.

Supporters of the bill say the enhancement at issue, although discretionary, affected one-third of people convicted in 2017. More than 10,000 people in California prisons are serving sentences that were affected by this enhancement. This does not reflect the effect of the law on the large numbers of people serving felony sentences in jails, under realignment.

One notable element of the one-year enhancement is the fact that it only applies to people whose previous felony convictions were punished with jail or prison sentences, and not probation. Harris argues that this bestows another relative advantage on people whose wealth, resources, access to legal counsel, or whiteness, made them likely to receive less harsh sentences for the same crimes—and conversely, another disadvantage on the low-income people of color who are overrepresented in California prisons and jails. The threat of enhancements can, of course, also be deployed during plea negotiations, just another element of prosecutors’ arsenal for extracting convictions and prison sentences.

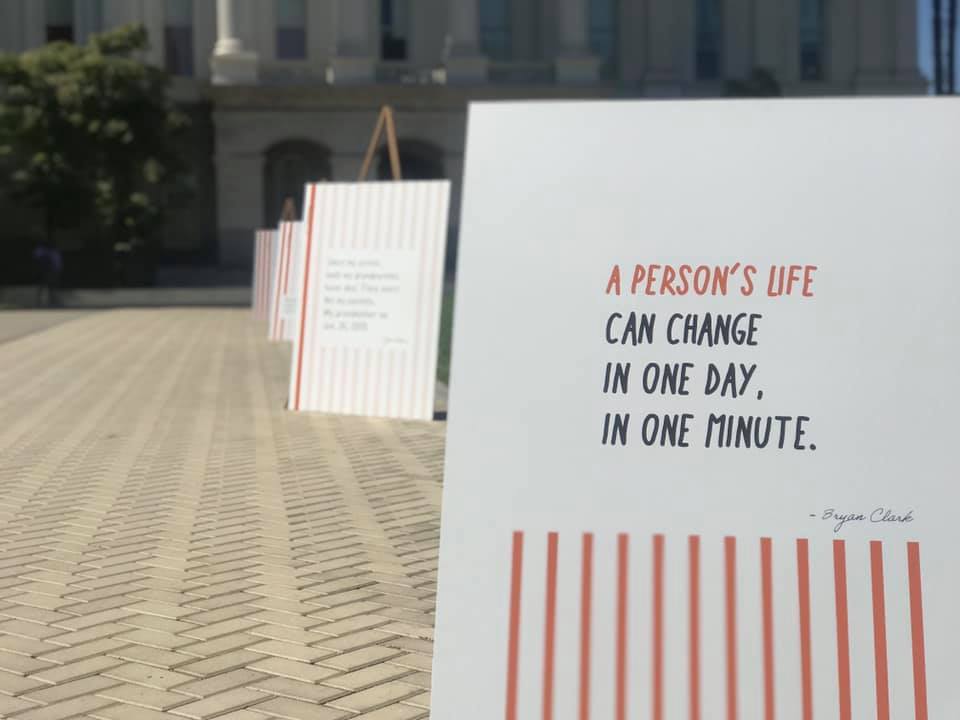

A recent press conference held by supporters of SB 136 featured an art installation at the state Capitol depicting “What a Difference a Year Makes.” The exhibit included the family milestones that people missed during just one year of incarceration: the birth of their first child, graduations, holidays, and deaths in their families.

James Vick was one of the people in prison quoted in the display. He said, “One year in this awful place can easily become a lifetime of misery, heartache, loneliness, pain, and uncertainty—because someone felt that a one-year enhancement was ‘only a year.’”

Other people shared their thoughts on what gaining a year of freedom could mean to them. They described how they would spend time at the bedsides of relatives fighting cancer, have the chance to raise their children so they could avoid the cycle of incarceration, and invest in themselves, their families, and their communities.

The gains would also be financial. A recent analysis of SB 136 by the state Department of Finance found that, if passed, the bill would save the state over $20 million in 2020-21. Savings would exceed $40 million the following year, and pass $60 million the year after that.

The organizations sponsoring the bill are the ACLU of California, California Coalition for Women Prisoners, Californians United for a Responsible Budget, Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights, Drug Policy Alliance, Ella Baker Center for Human Rights, Friends Committee on Legislation California, Legal Services for Prisoners with Children, Pillars of the Community, and Tides Advocacy. (The Appeal is a project of Tides Advocacy.)

Law enforcement groups have lined up in opposition to the bill. These include the California District Attorneys Association, the California Police Chiefs Association, and the California State Sheriffs’ Association.

Harris described the efforts in recent years to reverse the many policies that created California’s mass incarceration crisis. Even if SB 136 is passed, she emphasized, there is more work to be done. “We have been able to build and gain momentum around having the voters and legislators recognize the harm that imprisonment has caused, but we’re only at the beginning of the reversal. Mass incarceration was hundreds of thousands of policies and choices. There’s going to have to be thousands more decisions made to reverse them.”