The Untold Story of How a Stubborn Group of Parents Helped Shutter the Nation’s Largest Youth Prison System

How a scrappy group of parents played a key but lesser-known role in the pending closure of the Division of Juvenile Justice

This article is being co-published with The Imprint, a national nonprofit news outlet covering child welfare and youth justice.

Long before the “school-to-prison pipeline” was a well-worn phrase and even law-and-order Republicans had traded “tough on crime” for “smart on crime,” a tireless group of parents trekked, over and over, to the California state Capitol.

Their goal was as personal as it was quixotic: to shut down the California Youth Authority. At its height decades ago, the network of youth prisons held more than 10,000 young people, in conditions so inhumane that over one 18-month stretch in 2004, 56 teens attempted suicide.

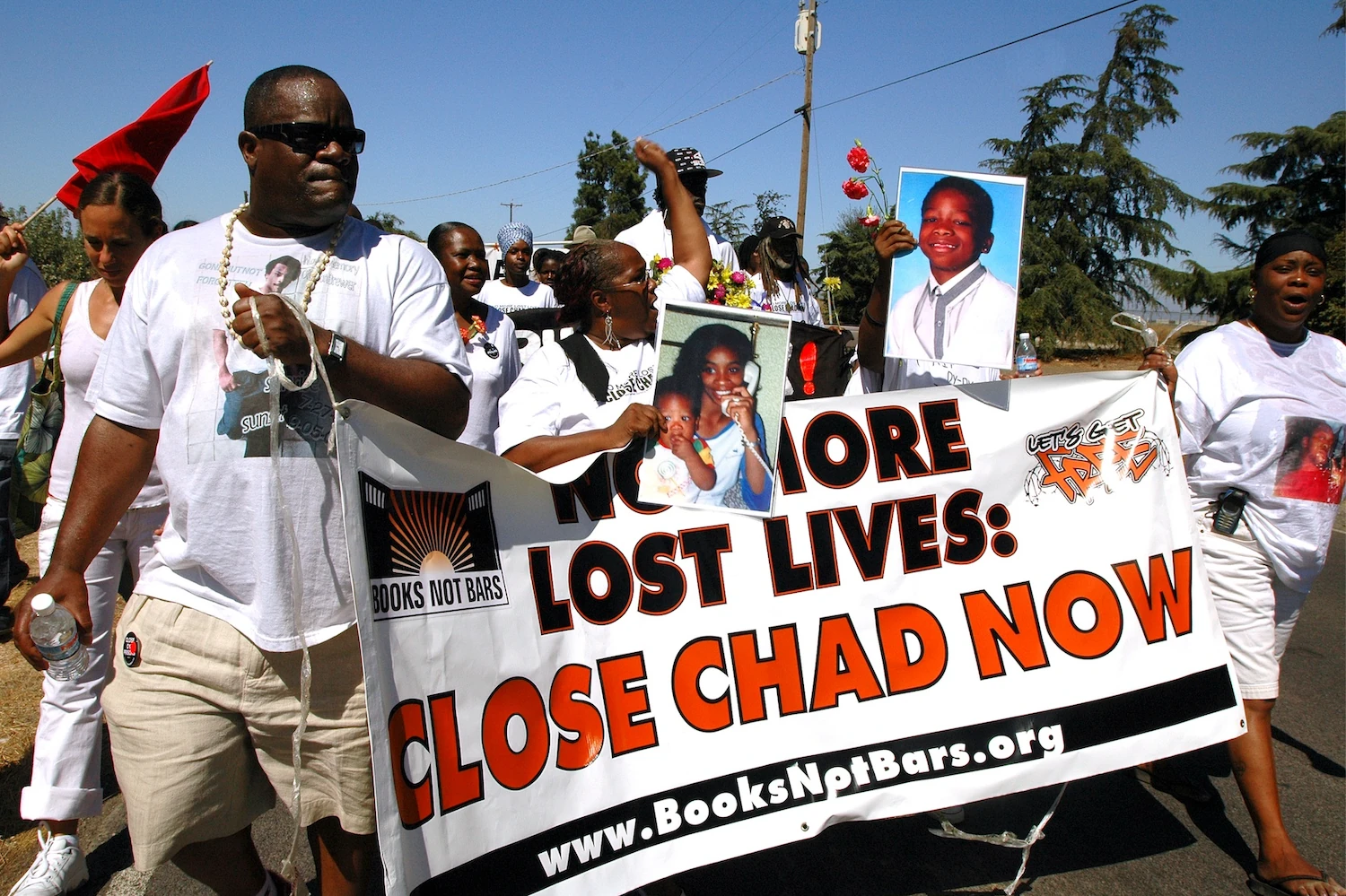

Even when the parents’ pleas were met with indifference inside the halls of the Legislature, they rallied on—hoisting poster boards with childhood photos of their sons and daughters.

“Books not bars!” they chanted, even when no one seemed to be listening.

The campaign slogan stuck. What the parents lacked in political power they made up in numbers. As many as 1,400 members would eventually join what came to be known as the Books Not Bars campaign, relentless advocates for children and teens locked up for crimes as serious as homicide and as commonplace as drug use and probation violations. Books Not Bars meetings became a lifeline for family members, who supported each other during the most difficult years of their lives.

“When you’re out there fighting for your child, it can feel like you’re on the battlefield by yourself,” said Katrina Allen of Fresno, one of Books Not Bars’ earliest and most outspoken members. “We were a family—a family of parents who had children in dire straits.”

There was little indication, back in those days, of the success these parents would come to achieve. But there were signs of their influence.

“Once you have parents in your face, up close and personal, and we’re bringing to you the things that our children are going through, you can no longer turn a blind eye,” Allen said. “Now, this had to be addressed.”

Once-unimaginable goal comes true

Amid the protests, for decades, prosecutors and judges continued to send tens of thousands of young people, some as young as 12, to the California Youth Authority’s 11 hulking warehouses. Serving indeterminate sentences, with “time-adds” for even minor infractions like getting in fights, some young people were held in prison cells for 23 hours a day or assaulted by guards. Punishments included being forced to attend high school classes in telephone booth-sized metal cages arranged in a semicircle. Larger cages the shape and size of shipping containers were used for individual exercise sessions.

In 2003, the San Quentin-based Prison Law Office filed the Farrell v. Harper civil suit in Alameda County Superior Court, alleging excessive use of force and sexual abuse by Youth Authority staff and “inhumane, filthy, stultifying housing conditions.” A year later, a judge signed off on a settlement requiring remedial plans to address deficiencies in safety, health, mental health care, education, sex offender treatment and disability services. The judge placed the entire youth prison system under the supervision of a special master and commissioned a series of reports that documented lack of education, medical neglect, and “stunning” levels of violence.

Thirteen years of court supervision ensued.

Then, in May of 2020, a newly elected Gov. Gavin Newsom—seeking to trim state costs in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic—slipped a stunning move into his first-ever state budget. The fresh-faced Democrat who had vowed early on to “end the juvenile justice system as we know it” quietly announced plans to shut down the state’s youth prisons entirely and return all occupants to facilities in their home counties. Newsom described the closure of the renamed Division of Juvenile Justice (DJJ) as the beginning of a new era in youth corrections.

For the parents who had long fought for this outcome, it represented the end of a nightmare.

“This is what we wanted,” said Katrina Allen. “It’s why we kept fighting. We were not going to be silenced.”

The lesser-known forces that brought down ‘CYA’

California halted all new intakes to state youth facilities in June of 2021, and will shut its last youth prison by June 30 of this year. Getting there has taken a decades-long collaboration among attorneys, justice advocates, the formerly incarcerated, legislators and reform-minded philanthropists.

Books Not Bars played a lesser-known but vital role.

The group began in 2002, when a small number of family members started meeting at Oakland’s nonprofit Ella Baker Center for Human Rights to discuss their imprisoned children’s fate and brainstorm how they might change that trajectory. These informal, private gatherings grew to public protests involving dozens of partner organizations.

The parents’ raw anguish made their voices difficult to ignore as they shared their stories with reporters, legislators, and anyone else willing to listen.

Laura Talkington-Brady of Fresno carried photos of her son’s bruised face when she attended the Sacramento rallies. They were taken after another detained youth beat him with a phone receiver, breaking his teeth and leaving him with 15 stitches.

Gloria Feaster, whose son Allen died at the Preston School of Industry in 2004, would describe what it was like to have the state ship her son’s body back after he was found hanging in a cell.

“We were holding vigils as often as we were holding protests,” said Zach Norris, who organized the group early in his career at the Ella Baker Center, where he would later become the executive director. “At one protest we’d be angry, shouting, ‘Shut it down.’ And then at the next, we were trying to support a family that had just lost someone inside the institutions.”

The personal stories also helped counter a false narrative that had hijacked the national conversation on crime and safety. During the 1990s, overheated rhetoric perpetuating racist myths and stereotypes dominated news cycles and the political discourse. California responded by building the nation’s largest youth prison system, filling its institutions with Black and brown teenagers from impoverished neighborhoods.

‘He was just being warehoused’

Allen, now 60, joined Books Not Bars after her then 16-year-old son was sent to a youth prison in 1999.

Her first encounter with the group was happenstance. She was leaving the N.A. Chaderjian Youth Correctional Facility in Stockton after a difficult visit with her son when she saw a small group of women handing out Books Not Bars flyers in the parking lot. Their ambitious slogan felt like a salve for the helpless rage buzzing through her body.

Allen’s son had been sentenced by a judge who she said promised her he would get help for her son’s symptoms of bipolar disorder. But every time the boy called home, “he had been in a fight or was in some type of trouble,” she said. “He wasn’t going to school. He wasn’t seeing a doctor or mental health counselor. He was just being warehoused.”

Books Not Bars members Caron Vaughn and Talkington-Brady introduced themselves to Allen with a handout inviting new members. They also had a question no one else was asking at the time: How was her son?

Allen called the number on the flyer first thing the next morning and soon she was attending chapter meetings in Stockton. There she met other parents who had children in the prison system for 12- to 24-year-olds.

At her first meeting, Allen listened in stunned silence as parents described finding their children covered in cuts and bruises each time they visited. She heard about Allen Feaster, a dedicated Books Not Bars leader whose son Durrell had been sent to the Preston School of Industry in Ione on a truancy charge. In 2004, Durrell was found dead in his cell along with his roommate Dion Whitfield, in what prison officials determined was a double suicide.

Allen barely made it through that first meeting.

“I went into a stall in the bathroom and cried,” she said. “I thought, ‘Where in the hell have these people sent my child?’”

Lenore Anderson’s first encounters with these parents as a young law student were equally horrifying.

“I was completely blown away by what I heard—parents were not getting even the most basic information about which facility their son is in, or whether or not visiting is open,” recalled Anderson, who went on to work as an organizer with the group. “Does the child have the medication they’re supposed to have? Parents lived in absolute terror over what was happening to their children.”

A daunting task

Books Not Bars was not alone in its fight. Civil rights attorneys, criminal justice experts and advocates worked over decades to improve conditions inside the California youth prisons, located from the Sierra Nevada foothills town of Ione to Whittier in Southern California.

Dan Macallair, the longtime director of the San Francisco-based Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice, was part of that informal but close-knit coalition.

He praised Books Not Bars because the group’s members did not settle for institutional reforms.

“They took a stand on closure. Right from the beginning, they were about closing the place down,” Macallair said. “They were a powerful force. They were organized. They had the parents, they had the kids, they had a good media presence; they were the voice that you never hear. Otherwise, it’s just the bureaucracies that control the message.”

The group drew respect from unexpected places, including from Karen Pank, longtime executive director of the Chief Probation Officers of California. Although the powerful lobbying group has opposed shut-down efforts on the grounds that California counties do not have the resources to properly treat the highest-needs youth in the justice system, many of its members shared parents’ concerns. Some probation officers told Pank they were “sick to their stomach when it came up to the time where a kid was being transferred to DJJ,” she said. “You really do stand shoulder-to-shoulder with parents in that situation.”

Nevertheless, the youth prisons remained open.

Norris recalled “a lot of frustration and butting our heads against the wall” during the early years. “Legislators were under the illusion that these kids are the worst of the worst and their parents don’t care about them,” he said. “Much of the initial work was to try to disabuse them of those stereotypes.”

Anderson described feeling the weight of the work the activists had taken on.

“I remember sitting in the parking lot looking at these massive structures and thinking, ‘How are we ever going to close this thing down?” she said. “I did not think that I would see it in my lifetime.”

Incremental progress

Meanwhile, fresh horrors continued to emerge, in newspaper exposés and court documents. At the Heman G. Stark Youth Correctional Facility in Chino, guards set up youth from rival gangs to battle in “Friday Night Fights.” At the Paso Robles Youth Correctional Facility, guards brought groups of youth to the gymnasium and forced them to kneel in shackles for as long as three days.

Legislative hearings ensued, including testimony from parents. It became increasingly clear that the Youth Authority was failing its state and legal obligations to provide the young people in its custody with treatment and rehabilitation rather than mere punishment. It also became clear that public safety was not being served by these institutions: 74 percent of those released were re-arrested within three years, according to state officials.

Meanwhile, the cost to taxpayers had soared to more than $250,000 per youth annually. In 2007, the state legislature passed Senate Bill 81, which allowed young people to be sent to state prisons only for the most serious and violent offenses, triggering a steep decline in the population and the beginning of facility closures. By 2010, the system held 1,262 youth. Four years later, the number dropped to 642 and continued to slide amid decreasing youth crime rates.

The rationale for keeping the state system open was crumbling.

The Books Not Bars campaign drew on the power of young people to make its case as well—primarily youth of color who had suffered the over-policing of their schools and neighborhoods and the disappearance of friends and classmates into the Youth Authority. They organized protests of their own, and fanned out in local parks and basketball courts with petitions calling for more investment in schools instead of prisons.

Will Roy, now 41, worked with Books Not Bars after he was released from the Youth Authority in 2003, and is now an associate director at the child abuse prevention group Safe and Sound.

In the early days, “it was hard for me to visualize a reality without prison,” he said, “because I couldn’t even envision my own freedom as an individual at the time.”

Twenty years later, he added, “what stands out for me is all the work it took—all the people, all the capacity and the resources that went into making these changes. It was like chipping away at a mountain with a chisel.”

A bittersweet victory

Today, the families of Books Not Bars are watching closely as California empties out its last three youth prisons in preparation for the final closure date in June.

According to a Feb. 22 report by the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice, “Crisis Before Closure: Dangerous Conditions Define the Final Months of California’s Division of Juvenile Justice,” four in ten staff positions were unfilled as of February, leaving young people locked in their cells for more than 14 hours a day. Youth on disciplinary units are allowed out of their cells for less than four hours a day. Drug overdoses are common, as is the use of pepper spray by guards.

So while the closure of California’s state-run youth prison system is a historic victory for activists, the cost remains steep. Among the Books Not Bars parents who lived to see the closure, there is a sense of somber celebration about the imminent demise of the bleak institutions that once held their children. Many are still struggling to heal families ripped apart by years of separation and trauma and rough homecomings for those who were released.

“These people destroyed this young man,” Allen said of her son, who spent six years in the youth lockups, much of the time in solitary confinement that was so common it was referred to as “23 and 1”—named for the 23 hours per day the youth spent locked in a cell with one hour of exercise, usually in an outdoor cage.

“He was already dealing with psychological and emotional issues,” she recalled. “When he came home, we did not know who he was.”

These days, Allen draws comfort from the knowledge that the movement she and other Books Not Bars members spearheaded will spare other families.

“The sweet part is that this hellhole is closed down and California will never raise up another system like it again,” Allen said. “I commend every last one of those warriors. Can you think of anybody else in your lifetime who went up against such a powerful entity and shut it down?”