Bill Challenging ‘Safekeeping’ of Tennessee Teens in Adult Prisons Could Soon Become Law

On Wednesday, May 16, 16-year-old Rosalyn “Bird” Holmes was able to walk out of prison and hug her mother. Though the teenager has yet to be indicted, let alone convicted, of any crime, she nonetheless spent the past 40 days in the Tennessee State Penitentiary, an adult women’s prison in Henning, Tennessee. Had it not […]

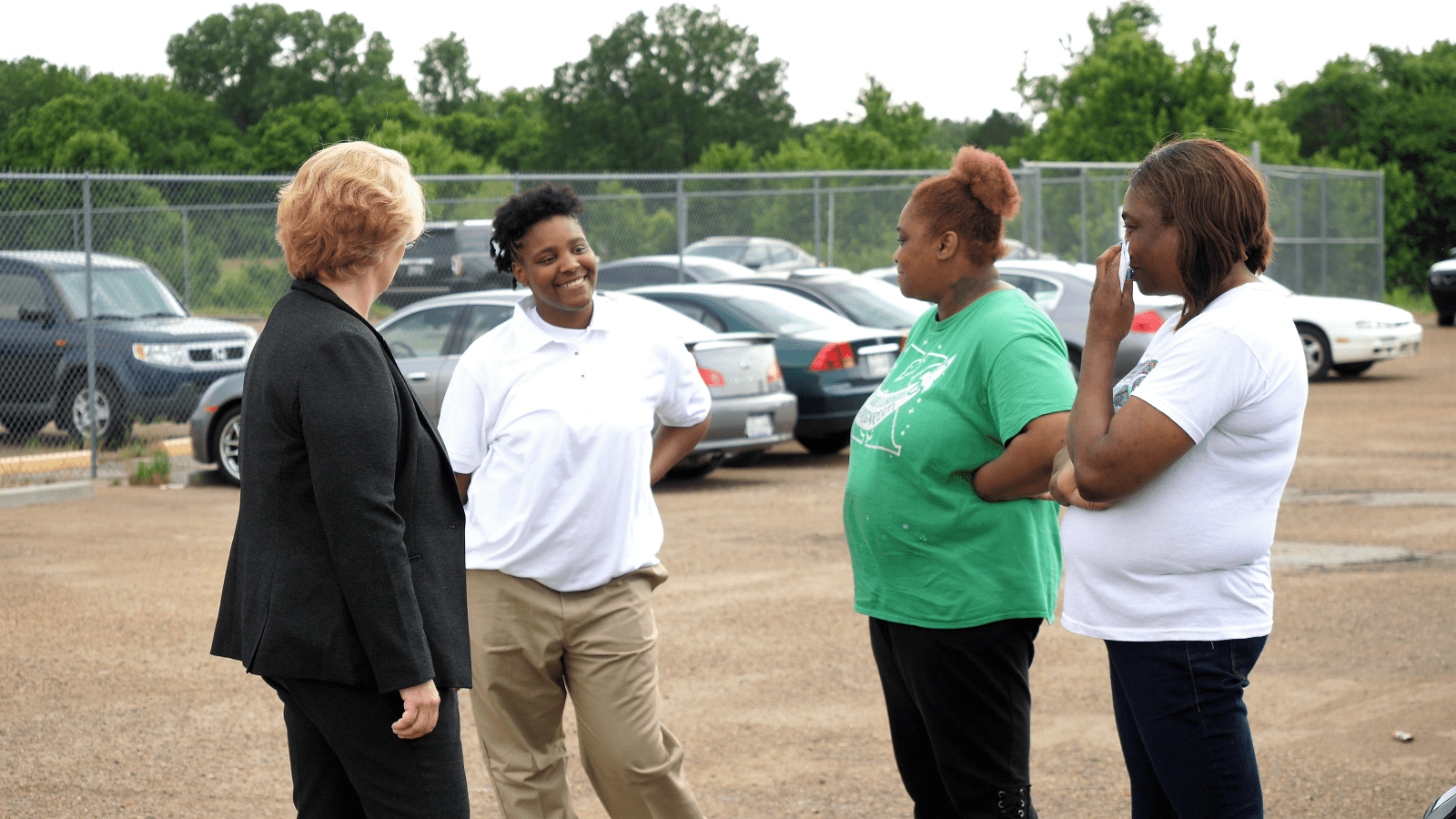

On Wednesday, May 16, 16-year-old Rosalyn “Bird” Holmes was able to walk out of prison and hug her mother. Though the teenager has yet to be indicted, let alone convicted, of any crime, she nonetheless spent the past 40 days in the Tennessee State Penitentiary, an adult women’s prison in Henning, Tennessee. Had it not been for the advocacy of Just City, a Memphis-based criminal justice organization, and the $60,000 bond posted by the Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights organization, Holmes might still be languishing in an adult prison awaiting her day in court. And she’s not the only teenage girl who has been sent to an adult prison without a trial or conviction.

Four months earlier, on January 27, Holmes was the passenger in a car with three other teenagers — two boys and another girl—who allegedly kidnapped at gunpoint, according to police. The four were arrested and charged with kidnapping and robbery. Holmes and the other girl were sent to the Shelby County Juvenile Detention Center while awaiting their day in juvenile court.

In February, Holmes turned 16. She remained in juvenile detention.

In mid-March, the courts decided that she could be tried as an adult — meaning that her case was transferred to adult court. She remained in juvenile detention until March 29 when the court held a “safekeeping” hearing to decide whether to transfer her to an adult facility.

Safekeeping in Tennessee dates back to an 1858 law allowing sheriffs and jailers to transfer a person to another jail or prison if their jails could not accommodate a person’s medical, mental health, or behavioral problems. The law continues to be used — between January 2011 and 2017, more than 320 people awaiting trial in Tennessee were confined to prisons under safekeeping. In 2017 alone, there were 86 people held as so-called “safekeepers.” Most are adults with medical conditions, including pregnancy, that the jail is not equipped to handle. But others are adults with mental health or behavioral issues or, as in Holmes’s case, teenagers facing adult charges.

The Tennessee Department of Correction policy mandates that those under safekeeping status be kept in solitary confinement.

That’s what happened to Teriyona Winton, a Memphis teenager awaiting trial in adult court. Winton was 15 years old when she was arrested and charged in the shooting of a 17-year-old boy. She was sent first to the women’s adult jail in Shelby County, then transferred to the Tennessee Prison for Women just outside of Nashville, more than 200 miles from her family in Memphis. But she wasn’t only isolated from her friends and family — she was also physically isolated in solitary confinement as both a safekeeper and because she was a teenager in an adult prison. She spent 23 hours a day in her cell, where she received all of her meals and a few hours of school instruction through a flap in her cell door. For the one hour she was allowed out of her cell — to shower or to exercise alone in the gym — her hands and feet were shackled.

Under the 2003 Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA), prison and jail officials must separate incarcerated children under age 18 from adults by “sight and sound.” In other words, incarcerated children are not allowed to be in places with their adult counterparts. But because so few girls are sent to adult prisons, this often means that they are kept in isolation until they turn 18. The adult prison system in Ohio, for instance, held one girl under the age of 18 in March 2018. The following months list no girls under the age of 18 in custody, though it is unclear whether the sole girl turned 18 and was moved to the adult section or was released from prison.

But in Shelby County, Tennessee, girls under the age of 18 are placed in prison — often in isolation — even before they are indicted, let alone convicted. Winton spent months in solitary before attorneys with Just City intervened. Even then, Winton wasn’t sent to juvenile detention where she could be around other girls — she was moved back to the women’s jail in Shelby County. When Holmes was declared a safekeeper in March, both girls were transferred to the Tennessee State Penitentiary where they were the sole occupants of a 158-bed unit.

“Every day was the same,” Holmes told The Appeal. The two girls were allowed out of their cells at 6 a.m. each day. A teacher came in and taught them for a few hours, they were allowed to go to rec, and they were able to watch TV. At 8:30 p.m., they were locked in their cells for the night. But, though they were allowed to move around the unit during the day, the monotony wore on them. “You get tired of the same thing everyday,” Holmes said.

Josh Spickler, executive director of Just City and Holmes’s attorney, notes that Shelby County is the only county in Tennessee that sends pretrial teenagers to adult prisons for safekeeping. “It’s the culture in Shelby County of treating Black bodies in a certain way,” said Spickler. “They’re kids on paper, but they’re treated as tiny adults. They’re seen as threats.”

According to Debra L. Fessenden, the chief policy and statutory compliance officer for the Shelby County Sheriff’s Office, juvenile judges determine where young people are housed, and there was nowhere to hold the girls apart from an adult prison. “There were no jails in the entire state which could do that, so there was no choice but to take the extraordinary measure of asking the state for help with their safekeeping.” But, she added, the sheriff and juvenile court judge are working “to obtain a location to house all Shelby County youth in a local facility with plenty of classroom and outdoor space.”

In April, State Senator Mark Norris filed an amendment to a bill that would prohibit sending teenagers to adult prisons as safekeepers. The amendment, which is retroactive, unanimously passed both houses of the state legislature later that month. On May 10, the bill reached the desk of outgoing Governor Bill Haslam, who has previously said that it “doesn’t make sense” to place teenagers who have not been convicted of a crime into an adult prison. He has 10 days to sign it into law or veto it. If he does neither, the bill automatically becomes law.

Holmes is now home, but only because the Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights organization posted bond. She’s not free either — though the judge waived a requirement for electronic monitoring, she is required to do day-reporting, which Spickler described as “like probation or parole but before conviction.” Speaking to The Appeal the day after her release from adult prison, Holmes said, “It’s not a place where teenagers should be. Keep them around other people their age.”

Meanwhile, Winton remains in the Tennessee State Penitentiary — alone. Shortly after Holmes was released, she used the prison’s e-messaging kiosk to write to Spickler. “Bird left. What happens now?”