Commentary

Biden’s Cannabis Pardons Made Progress. A Federal Expungement Statute Would Go Further.

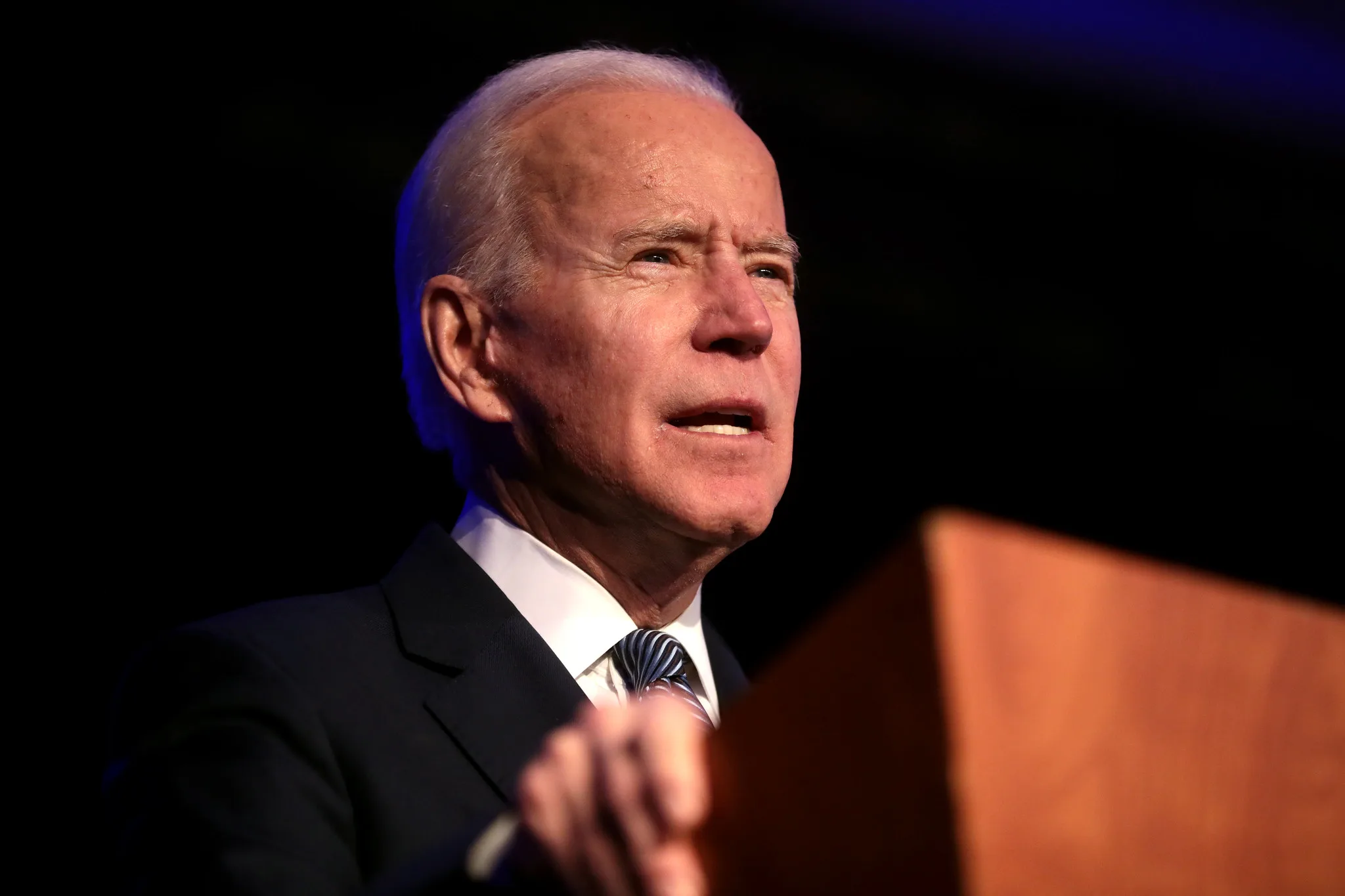

President Biden has pardoned thousands of people for cannabis-related offenses. But to truly give people “second chances,” he should push Congress to erase peoples’ marijuana-related criminal records entirely.

This piece was published in coordination with Zealous, an organization working to challenge injustice through media, storytelling, and the arts.

Since 2017, April in America has marked “Second Chance Month,” a program to raise awareness about the harms of the criminal legal system. In a March 29 statement on the upcoming events, President Joe Biden recommitted to America’s “promise to new beginnings” while touting his cannabis reforms. The president referenced his October 2022 proclamation asking federal officials to review cannabis’s Schedule I substance classification and also mentioned the people with federal marijuana possession convictions that he has pardoned.

While Congress has not changed any federal laws, Biden’s words matter. In raising this issue, Biden brought greater awareness to cannabis policies, the broader drug reform movement, and the need to remedy the atrocities of the failed drug war.

But Biden’s specific words matter, too. The President has repeatedly—including in his 2024 State of the Union address—wrongly claimed he has “expung[ed] thousands of convictions for [possession of marijuana] because no one should be jailed for simply using or having it on their record.” As a drug reform advocate, I know the message’s intent was significant. Yet, as a criminal justice practitioner, I felt the perennial frustration of politicians conflating words used in the context of record clearance—in this case, incorrectly conflating pardons with expungement.

Since expungement does more to clear a person’s name than a pardon, the president has thus inflated his impact on current or formerly imprisoned people. But there is one way President Biden can remedy this issue: by supporting a federal expungement statute.

The term “expungement” can mean slightly different things depending on the jurisdiction. The word generally refers to a criminal record’s destruction or complete erasure. Biden instead only pardoned individuals with federal possession convictions—a process that nullifies and forgives a person of a conviction but does not erase the record. Pardons are the one mechanism available within the president’s executive authority.

However, pardons do not alleviate the collateral consequences of convictions.

In my practice, I have helped individuals successfully expunge their records and apply for pardons. Unfortunately, when a pardon is the only record relief option available, the people I work with still face obstacles.

Since a pardoned offense still appears on one’s criminal record, many of the most detrimental collateral consequences, including barriers to employment, housing, and consumer loans, are not addressed, even when the action comes from the president.

This is not a critique of the president’s actions thus far. He has used his available executive powers to clear the records of thousands of Americans. But the fact that Biden can take no further action on his own means that we need to reexamine the types of relief available to people convicted of federal marijuana offenses. The answer is a federal expungement statute to seal or erase certain arrests or convictions automatically.

The president is on board: in his State of the Union address, he said no one should be in jail or have a conviction on their record for using marijuana. During the 2020 campaign, Biden promised bold action on criminal justice reform. Four years later, he can take a step in the right direction by urging Congress to pass a federal expungement statute that would address cannabis offenses.

Such a statute is a common-sense policy. There are currently several pending bills—with broad, bipartisan support—to introduce general federal expungement and sealing language. (One bill, for example, would automatically seal records of any nonviolent conviction or for any charges that were later dropped or acquitted.) Additionally, most of the federal cannabis legalization bills that have been introduced include provisions for expunging federal marijuana offenses. Multiple states—including California, Pennsylvania, Oklahoma, and Utah—have already passed robust expungement laws with bipartisan support. These laws have expunged nearly two million records, but passing legislation like the recently reintroduced HOPE Act would further cover the costs of expunging cannabis offenses in legal states.

Cannabis legalization has often incited states to enact more expansive and efficient forms of record clearance overall. The federal government’s imminent reclassification of marijuana is an opportunity to move in a positive direction. While the President’s cannabis pardons have brought minimal relief to thousands of people, even a pot-specific federal expungement statute could bring meaningful relief to millions of Americans. While federal cannabis legalization legislation continues to stumble in Congress, a federal expungement statute that includes relief for cannabis-related offenses appears much more politically viable.

By finally passing a general federal expungement statute, the federal government could fulfill the President’s aim of alleviating the harms caused by the criminalization of cannabis, as well as a broader class of federal convictions. The federal government needs to follow the direction of most states that have enacted some form of record clearance. Doing so would help those who have served their time rebuild their lives and rejoin society.

Sarah Gersten is the executive director and general counsel for the Last Prisoner Project, a nonprofit dedicated to freeing those incarcerated due to the War on Drugs, reuniting their families, and helping them rebuild their lives. She is also a member of the National Cannabis Bar Association, the NORML Legal Committee and the National Lawyers Guild.