‘Basically Cyberbullying’: How Cops Abuse Social Media to Publicly Humiliate

Law enforcement agencies are creating online content, often at the expense of people they have arrested.

On Oct. 22, the Mobile County sheriff’s office in Alabama featured Jordan Brown as its “thug” of the week. Along with Brown’s mugshot, the department posted a 150-word caption (including joking hashtags and emojis) to its Facebook page, calling on Brown to turn himself in after allegedly stealing a car while being out on bail for another offense. “Today our THUG is JORDAN SCOTT BROWN #weknowhimwell,” it reads. The post garnered hundreds of likes, shares, and comments, many poking fun at Brown’s troubles, criticizing his appearance, and mocking his intelligence. One comment crudely alluded to sexual violence Brown could encounter if incarcerated.

Six weeks after the initial post, Mobile County sheriff’s office featured Brown’s mugshot on its “Thug Tree,” a picture of a Christmas tree photoshopped to look like it was decorated with mugshots and topped with the orange sandals similar to ones that are issued to people entering Mobile Metro Jail. The tree’s image was posted to the office’s Facebook account.

The caption accompanying the post invites all “thugs” in the county to pick a stolen item from its property room, after which “your very own personal concierge #correctionsofficer” will “take you for a ‘custom fitting’ to receive your Holiday jumpsuit.”

The post was widely shared and drew condemnation from criminal justice advocates, the faith community, and the public. Reverend David Frazier Sr. a Mobile pastor and vice chairperson of the Faith in Action Alabama Mobile hub, said leaders in the community were shocked by the “Thug Tree,” which he called a “sacrilegious” act. Several local organizations, including Faith in Action Alabama, organized a protest outside the sheriff’s office, demanding an apology. One commenter on Twitter asked: “Why does law enforcement have to be so heartless?”

Police departments have said that maintaining a presence on social media and direct engagement with the community builds trust and leads to arrests of people with outstanding warrants by soliciting crime tips. But a trend has emerged on social media accounts run by law enforcement: a hypermalicious form of voyeurism and public humiliation targeting people who have been arrested or just suspected of a crime. Critics argue that this form of “engagement” does not reduce recidivism and can often do more harm than good.

The Mobile County sheriff’s office deleted the post, telling a local NBC affiliate it had received threats to deputies’ safety. But despite the outcry, the office has continued the “Thug Thursday” Facebook series at the request of its followers, said Lori Myles, spokesperson for the sheriff’s office.

“Our goal is making the arrest and getting that criminal off the street,” Myles said. “We use the definition of THUG as what is in the dictionary…a criminal.”

This is not the first time Mobile’s law enforcement agencies have been criticized for their social media posts. Last year, the Mobile Police Department came under fire for a photo of two officers holding a “homeless quilt,” a collection of taped cardboard signs that had been seemingly confiscated from unhoused people.

Law enforcement has even gamified digital mugshots in recent years. In 2011, Joe Arpaio, former sheriff of Maricopa County, Arizona, created an online program called “Mugshot of the Day,” which allowed the public to “vote” on a favorite mugshot each day. In 2017, Florida’s Escambia County sheriff’s office debuted its “Wheel Of Fugitives,” a show broadcast on local news during which officers spin a game-show style wheel that lands on mugshots of people wanted for arrest; the mugshot that the “Wheel of Fugitives” selects is also featured on billboards throughout town. In Florida’s Brevard County, Sheriff Wayne Ivey produces YouTube segments called “Fishing for Fugitives,” where the sheriff solicits tips on a person he dubs the “Catch of the Day,” in addition to hosting his own “Wheel of Fugitives” show.

In Maryland, the Harford County sheriff’s office uses Old West-style wanted posters sometimes paired with derisive captions to release information about people with warrants. Florida’s Pasco County sheriff’s office drew criticism in 2016 for its “Sad Criminal of the Day” Facebook and Twitter posts that showed Marquis Porter, a man detained for drug possession and other charges, sitting on the ground and crying as deputies held chunks of his hair.

In the United States, mugshots are classified as public record, and most law enforcement agencies can use them on social media at their discretion. One theory of why the public reacts with such zeal to mugshots is the concept of “penal spectatorship,” a term coined by sociologist Michelle Brown that explains ways in which society participates in determining people’s guilt.

Sarah Lageson, an assistant professor of sociology at the Rutgers School of Criminal Justice, said that people often engage with posts like the Mobile County sheriff’s office’s because it allows them to “get in on the action,” as much of the criminal legal system is not public-facing. Their engagement works like a “dopamine trigger” for police, she said, which fuels them to keep pushing for likes and shares. “It’s just a very, very different public role than law enforcement has ever played,” she said.

Many of these posts feature people with warrants for violation of parole, failure to pay fines and fees, minor drug offenses, trespassing, or petty theft. Since April, only three of 23 ,“Thug Thursday” posts calling for tips were for alleged violent crimes. A study from the Vera Institute of Justice found that in 2016 over 80 percent of arrests in the U.S. were for low-level offenses, “such as ‘drug abuse violations’ and ‘disorderly conduct.’”

When [police are] using social media to shame people who have been arrested, it’s also creating narratives that justify ongoing policing and ongoing arrest.

Rachel Kuo co-author #8toAbolition

Additionally, mugshots and news coverage often disproportionately link Black people with criminality. In 2015, several news outlets reported on the difference between two sets of photos used in similar stories in Iowa, only days apart. When three white men were arrested on alcohol-related charges and suspected of burglary, their wrestling team portraits were used in news coverage; when four Black men were arrested for burglaries, the news report featured their mugshots. Robert Entman and Andrew Rojecki, authors of “The Black Image in the White Mind,” found that mugshots were more likely to be shown in news stories about Black defendants. In 2015, a Florida police department was caught using mugshots of Black men as target practice at a gun range.

“Mugshots … reflect who the police decided to arrest, which is structured by race, class, gender, and where you live,” Lageson said. “And then we use the mugshot to evaluate a person. We use it as a marker of somebody’s worth and it’s before guilt, before conviction.” The police using mugshots on social media “doesn’t comport with due process and our constitutional rights,” Lageson said.

When police use social media to humiliate, the person in question isn’t the only one who feels the sting. Family, friends, and loved ones are swept up into the wide net of shame cast by agencies whose duties include protecting and serving them.

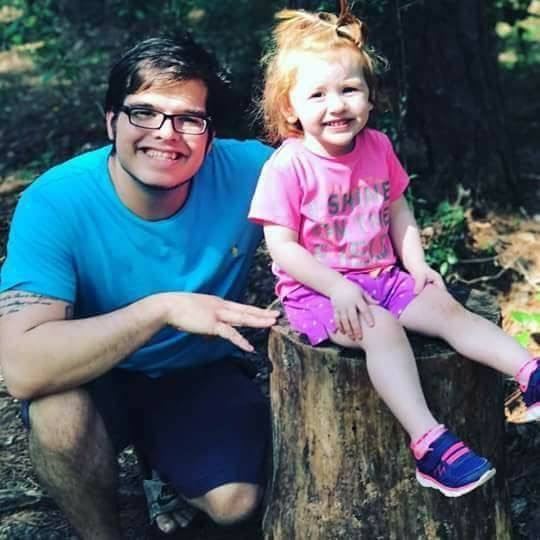

Karlee Brown, Jordan’s sister-in-law, learned that the Mobile County sheriff’s office featured Jordan on its Facebook page after her sister sent her the “Thug Thursday” post. Karlee was appalled after reading the crude caption and comments left by others about Jordan, who is struggling with a methamphetamine addiction. She said Jordan is a sensitive person and the social media pile-on since his arrest has put him at a higher risk to use drugs and self-harm. Karlee also pointed out that the use of a Christmas tree in the “Thug Tree” post adds insult to injury for the loved ones of those featured since many will be incarcerated on Christmas.

“These officers and departments are supposed to be there to protect the public,” Karlee said. “It seems to me that all they are doing in these posts are basically cyberbullying these people, and opening the door for others to join in and do the same.”

Jennifer Collier, Jordan’s mother, was deeply affected by a comment left by a stranger on the “Thug Thursday” post that said her son will “never change” and that he should be “put to sleep.”

Some research suggests that certain types of shaming can be counterproductive to the rehabilitation of someone who committed a crime. Criminologist John Braithwaite posits in a 1989 study that “reintegrative shaming” separates the person from the criminal act and focuses on changing behavior, while “disintegrative shaming” focuses on stigmatizing the individual, leaving them “isolated and humiliated.” And a 2011 study, which cites Braithwaite’s work, found that shame is “associated with outcomes directly contrary to the public interest” including denial of responsibility, substance abuse problems, and psychological symptoms.

An unfavorable digital history can make it harder to find employment, secure housing, and develop relationships. “You would think that [the police] would want them to get their life together and prosper instead of just continually trying to bring them down and bring them down and break them down. And that’s what I feel it does,” Collier said. “Jordan is a great person. He loves his children. He’s just kind of lost.”

The stigma surrounding any involvement with law enforcement can make re-entry difficult for formerly incarcerated individuals. “Stigmatizing people, public humiliation, and basically ensuring they can’t get a job or find a partner or have stable employment leads to more crime,” Lageson said. “If you really care about public safety, you should care primarily about rehabilitation and preventing this stuff in the first place.”

Over the summer, San Francisco Police Chief Bill Scott announced that the department will no longer post mugshots online or release them to the public unless they pose a threat to the public, a move that aims to curb “an illusory correlation for viewers that fosters racial bias.” Media conglomerate Gannett has removed all mugshot galleries on its digital properties. Last year, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo released a proposal that would bar state law enforcement agencies from releasing mugshots to curtail “unwarranted invasion of personal privacy.”

For some, these measures represent a step in the right direction but more is needed to address the critical failings of the U.S. criminal legal system.

Researcher and educator Rachel Kuo is a co-author of #8ToAbolition, a detailed, eight-step action plan for abolishing police. “When [police are] using social media to shame people who have been arrested, it’s also creating narratives that justify ongoing policing and ongoing arrest,” Kuo said.

Kuo also noted that when police use social media to shame, blame, and exact revenge on people, those carceral attitudes and that culture of punishment seep into our communities. Divesting from police departments and reinvesting in accessible healthcare, housing, and education, and building models for “non-coercive mental-health support, crisis intervention, and community-based violence prevention” are part of the structural changes she says are needed to dismantle the punitive institutions currently in place.

“Many of the things people are criminalized for have to do with survival,” Kuo said, noting that people who are unhoused, for example, may be more vulnerable to arrest.

Frazier, the Mobile pastor, said that people who have been arrested “shouldn’t allow those who are in law enforcement to demean them in such a way that they lose hope in themselves. Good people make bad decisions sometimes.”