At Angola Prison, ‘People Are Suffering. People Are Dying’

Trial begins in class action suit alleging medical neglect by Louisiana State Penitentiary.

“[T]he Louisiana State Penitentiary’s delivery of medical care is one of the worst we have ever reviewed.” That’s what two doctors and a nurse practitioner concluded in a report prepared for a trial that started this week stemming from a 2015 class action lawsuit.

Dr. Michael Puisis, an expert in correctional medicine, argued on the stand Wednesday that Louisiana State Penitentiary, known colloquially as Angola, had long neglected its duty to keep prisoners safe. A large part of that, he testified, was the failure of the Louisiana Department of Corrections to implement a system to review prisoner deaths or physician errors. “If you don’t look for problems, you don’t find them,” Puisis said.

A group of individually named prisoners, along with the Southern Poverty Law Center, the ACLU of Louisiana, the Advocacy Center of Louisiana, Cohen Milstein Sellers & Toll PLLC, and the Promise of Justice Initiative, brought the class action suit against the prison and the Louisiana Department of Public Safety. It alleges that, for a quarter of a century, they have run an unconstitutional healthcare system for the 6,000 people incarcerated in Angola.

“People are suffering. People are dying,” said Mercedes Montagnes, executive director of the Promise of Justice Initiative and lead counsel on the case. “It is our sincerest hope that this suit will ensure that the state of Louisiana treats all its people with basic decency and in accordance with the Constitution.”

The 90-page medical report discussed in court Wednesday describes delays, denials of treatment, inadequate care, and a lack of accountability for physicians, violating rights guaranteed by the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition on “cruel and unusual” punishment. In one case involving a prisoner who was a double-amputee suffering from necrosis, for instance, Puisis told the court he had “never seen that extent of dead tissue in a patient.” Another patient, since deceased, went 16 months without a biopsy for a mass in his lung that turned out to be cancer.

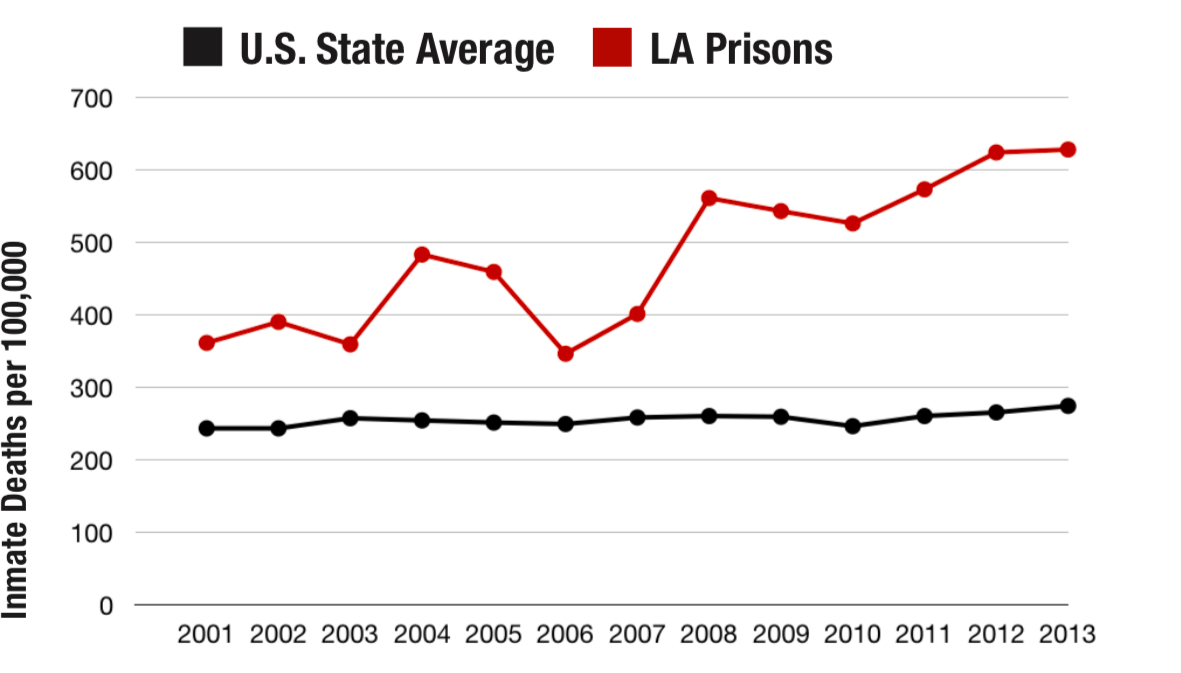

Puisis also pointed to the near doubling of mortality rates in Louisiana state prisons, from 361 per 100,000 prisoners in 2001 to 628 in 2013 (the last year data is available), which is the highest death rate of prisoners in the country. The number, the experts explained, could not be attributed solely to the prison’s aging population. The state’s Department of Public Safety and Corrections declined to comment on the trial, noting that it does not “comment on pending litigation.”

At Angola, the average prisoner age is just over 40, and the average sentence is in excess of 90 years, far beyond the prisoners’ expected life spans. The vast majority of prisoners are assigned to “hard labor,” working the 18,000 acres of crops, bending and toiling outside all day in all weather. The plaintiffs say these conditions all contribute to the current healthcare crisis. Puisis said the fact that the mortality rate nearly doubled over ten years suggests “something is happening in Louisiana that is really amiss.”

Puisis said the problems start with the process of evaluating prisoners for health issues. He said EMTs make the initial evaluation for “sick calls,” which often occur in the middle of the night when prisoners who want to see a physician for any reason are required to present themselves for a preliminary exam. Prisoners with chronic and painful health problems are also frequently denied narcotics, he noted, because of misdiagnosis or because staff don’t believe the prisoners are in pain.

Puisis and his colleagues also called into question the quality of the staff. Louisiana guidelines permit the Department of Corrections to hire physicians with restricted licenses and, according to the report and publicly available information, the Louisiana State Board of Medical Examiners had at some point suspended or restricted the licenses of all the physicians at Angola when the report was written.

The current director of medical services, Dr. Randy Lavespere, had his license suspended from 2006 to 2014 based on his felony conviction for possession with intent to distribute meth. According to the medical examiners board and as noted in the expert report, he was diagnosed with an unspecified personality disorder and has testified previously that he thinks half of his patients are faking their symptoms. As the report documents, other doctors on staff had their licenses suspended or restricted for concerns like sexual misconduct, drug and alcohol dependency, and a federal conviction for selling human growth hormone. Lavespere is in charge of monitoring all of the other doctors, which Puisis argued presents an inherent risk to patient safety.

Puisis also blasted the prison for an official policy allowing prisoners to be punished for “aggravated malingering,” a label applied to people who are deemed by staff to have requested unnecessary healthcare. “Medical staff shouldn’t be assigning punishment,” Puisis testified, because it violates agreed-upon standards for correctional health care. “It’s inappropriate, unprofessional and perverse,” he elaborated under cross-examination.

Earlier in his testimony Wednesday, Puisis raised concerns over the prison’s funding. From 2001-13, Angola spent less than half as much on healthcare per prisoner than the average for prisons nationwide. Puisis said administrators at Angola were unable to provide a line-item budget on its spending.

Puisis’s report provides context that could bolster the case brought by the named plaintiffs, who represent some of the most egregious cases of medical neglect. Otto Barrera, who lost most of his lower jaw in a 2012 shooting before arriving at Angola, appeared in the courtroom in shackles on Wednesday. Barrera was referred for reconstructive surgery in 2014 on his missing bottom lip and tongue, but Angola’s administration denied the procedure. Because he cannot chew his food, he is supposed to be on a soft diet. But, according to the complaint, he continues to receive the same meals as other prisoners, which he must tear into small pieces and painfully chew.

Advocates say the lawsuit highlights a problem plaguing Louisiana’s prisons overall: too many prisoners who are aging during their extremely long sentences. “This lawsuit should remind legislators that Louisiana is at a crossroads,” Norris Henderson, executive director of Voice of the Experienced, and a member of Louisianans for Prison Alternatives, later told The Appeal. “The state can either spend more money to provide adequate healthcare or it can incarcerate fewer people.”