As Use of Solitary Confinement Surges, Advocates Call for Releasing Prisoners

Legal, medical, and religious groups warn in a new report that the widespread use of solitary confinement in response to COVID-19 risks spreading the disease further and undoing a decade of progress.

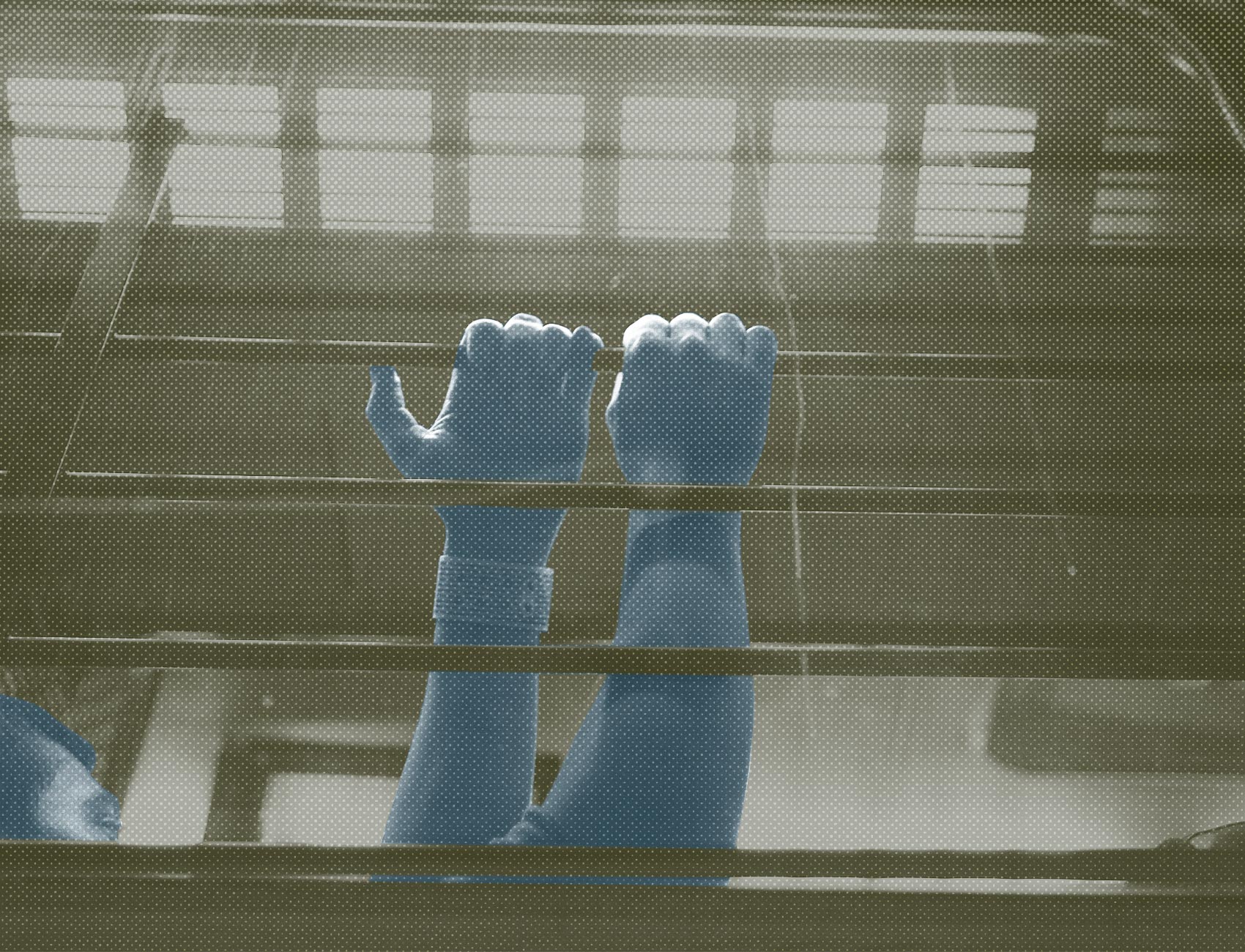

Corrections officials are confining people to their cells in prisons, jails, and detention centers at alarming rates in response to COVID-19, but advocates say the practice risks wider transmission of the disease, and are calling instead for large-scale decarceration.

A report released this week by the Unlock the Box Campaign, a national coalition of legal, medical, and religious groups, found that federal and state prison systems across the country have subjected upward of 300,000 people to solitary confinement in response to the public health crisis. That count excludes many thousands more who are locked down in dorms or camps, but not necessarily in their cells, according to Jean Casella, co-director of Solitary Watch, which is part of the coalition.

Many of those trapped in small cells in lockdown—for up to 22 to 24 hours per day, with limited access to mess halls, showers, and common areas—are confined with cellmates, a practice decried by advocates as deadly.

“We’re hoping that what’s going on with the pandemic and the protests and the pandemic are going to lead to positive and permanent changes in our prison system,” Casella said. “But we’re in danger of losing the ground that we’ve gained in reducing the use of solitary.”

Such measures, according to the report, are not just inhumane and unnecessary, but are most likely contributing to the spread of COVID-19 within prisons and jails, and in the communities around them.

In a Tuesday press call, Brie Williams, founder and director of Amend, a group of medical and public health experts at the University of California, San Francisco, said “the use of indiscriminate solitary confinement in response to COVID-19 deters people from reporting symptoms.” She added that “this in turn threatens the health of all those who live and work in the facilities.”

While the report recommends a number of public health measures to reduce the spread of the disease—such as rapid testing to isolate sick people and divide others into “cohorts” based on their infection status—the report recommends first and foremost that jails and prisons decarcerate, or release people held there.

“Releasing people from correctional facilities before the virus spreads further is … the swiftest and surest way of protecting the wider communities to which both incarcerated people and staff will return,” the report reads. “The short stays and high turnover rates in local jails, in particular, mean infections that begin behind bars do not stay there.”

And reducing the number of incarcerated individuals, the report says, will create “more of the space necessary for social distancing and the health care resources necessary for containing and treating COVID-19.”

Each week, as many as 200,000 people enter often cramped, unsanitary U.S. jail facilities and as many leave to re-enter their communities. In New York City jails, nearly 30 percent of the roughly 20,000 people admitted during the first half of 2019 stayed for four or fewer days. Staff members also come and go each day, adding to the turnover.

Prisons, which have less frequent turnover but can have similarly unhgyenic conditions, have also become the country’s most persistent hot spots, reporting high infection rates even without widespread testing.

A number of jails and prisons around the country have heeded the calls of public health experts to decarcerate. In April, the state of California temporarily suspended its cash bail system for certain low-level offenses to reduce the number people held pretrial. In Denver, officials decreased the jail population by as much as 41 percent by letting out medically vulnerable individuals.

In early April, the Bureau of Prisons locked down all of its 122 facilities in response to growing outbreaks inside. Just two weeks ago, the agency again locked down all of its facilities, this time stripping incarcerated people of all communication with the outside world and with a completely new justification: to maintain “the good order and security” of federal prisons amid nationwide protests against police brutality.

The surge in the use of isolation is especially alarming to advocates, Casella said on the call, because the movement to abolish solitary confinement has made significant progress over the last decade. Since 2011, when the United Nations special rapporteur on torture decried the practice as a form of torture prohibited by human rights law, it has come under scrutiny by President Barack Obama, Pope Francis, Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy, and a growing number of health experts, judges, and lawmakers around the country.

And advocates also say there is reason to fear that isolation implemented as an emergency response to COVID-19 will remain in place long-term. According to the report’s authors, the modern use of solitary confinement can be traced back to the 1980s, when the Bureau of Prisons responded to unrest in facilities with emergency lockdowns.

Casella cited in particular the case of Marion, a federal prison in Illinois that, in 1983, was put on lockdown following the deaths of three people inside. The prison remained on lockdown for 23 years, until it was eventually renovated and converted.

“The COVID crisis could last for years,” Williams said on the call, adding that the oft-repeated 12- to 18-month timeline for the development of a vaccine is just an estimate. “We can’t continue doing this, for multiple months and years on end.”

Josh Manson is a contributing writer with Solitary Watch.