This Deep Red State Just Ended Cash Bail

Alaska’s new comprehensive criminal justice reform law will reduce the prison population by 13% and save taxpayers $380 million.

It happened with scant fanfare, but January 1st marked an important step on the path to eliminate the country’s money bail system: it all but disappeared in the state of Alaska.

The state’s reform law passed with bipartisan majorities and was signed into law back in July 2016, but it has now finally taken effect. Before New Year’s Day, the vast majority of people arrested in Alaska had to post bail, usually an amount in the thousands of dollars, in order to be released ahead of their trials. As a result, people without resources overwhelmingly ended up behind bars. Those with money walked free.

With the dawn of the New Year, the state changed over to a completely different system. Now, when someone is charged with a low-level crime, he need not scrape together cash or secure a bail bond to get out of jail. Instead, the state’s newly created Pretrial Enforcement Division, housed in the Department of Corrections, will generate a risk assessment for him using a point system that is meant to determine whether he will be likely to show up to subsequent court appearances and unlikely to commit crimes while released. The assessment produces a “risk score,” using an algorithm created by an institute in Boston based on how frequently he’s failed to appear in court previously, the number of prior arrests or convictions, how many times he has been jailed and/or on probation, the crime he was arrested for, and the age of his first arrest.

Judges then review defendants’ risk scores. The law requires pretrial officers to make certain recommendations to judges based on a defendant’s charge and score, although prosecutors and defense attorneys can still argue for harsher or lighter restrictions on release, such as requiring drug tests or electronic monitoring. But secured bail bonds can only be set for those charged with violent offenses and with high scores. The law requires courts to release on recognizance those charged with nonviolent misdemeanors and class C felonies with low scores, and there is a presumption of release for everyone who falls in between.

Defendants who are released will then be monitored by pretrial service officers. “More people will be out, but more people will have supervision,” Nancy Meade, general counsel of the Alaska Court System, told Juneau Empire.

Risk assessment tools have been implemented in a number of jurisdictions that have reformed bail, such as Kentucky and New Jersey. While advocates generally favor their use over bail, many express serious reservations about the tools. For example, people fear the tools can be discriminatory because they rely on past criminal history — which itself is already skewed, given how much more likely people of color are to be stopped by police and arrested in the first place. Casey Reynolds, communications director for the American Civil Liberties Union of Alaska, told the Fairbanks Daily News Miner that his organization supports replacing cash bail with the new point system because bail “puts people’s rights in a situation where it’s predicated on how much money you have.” But, he added, they will monitor to make sure that the new system is effectively administered. “We, like a lot of other people, have questions about how the new methodology is going to work and how it’s going to play out in practice, and we are watching it closely, but it’s probably going to take six months to see exactly how it’s working.”

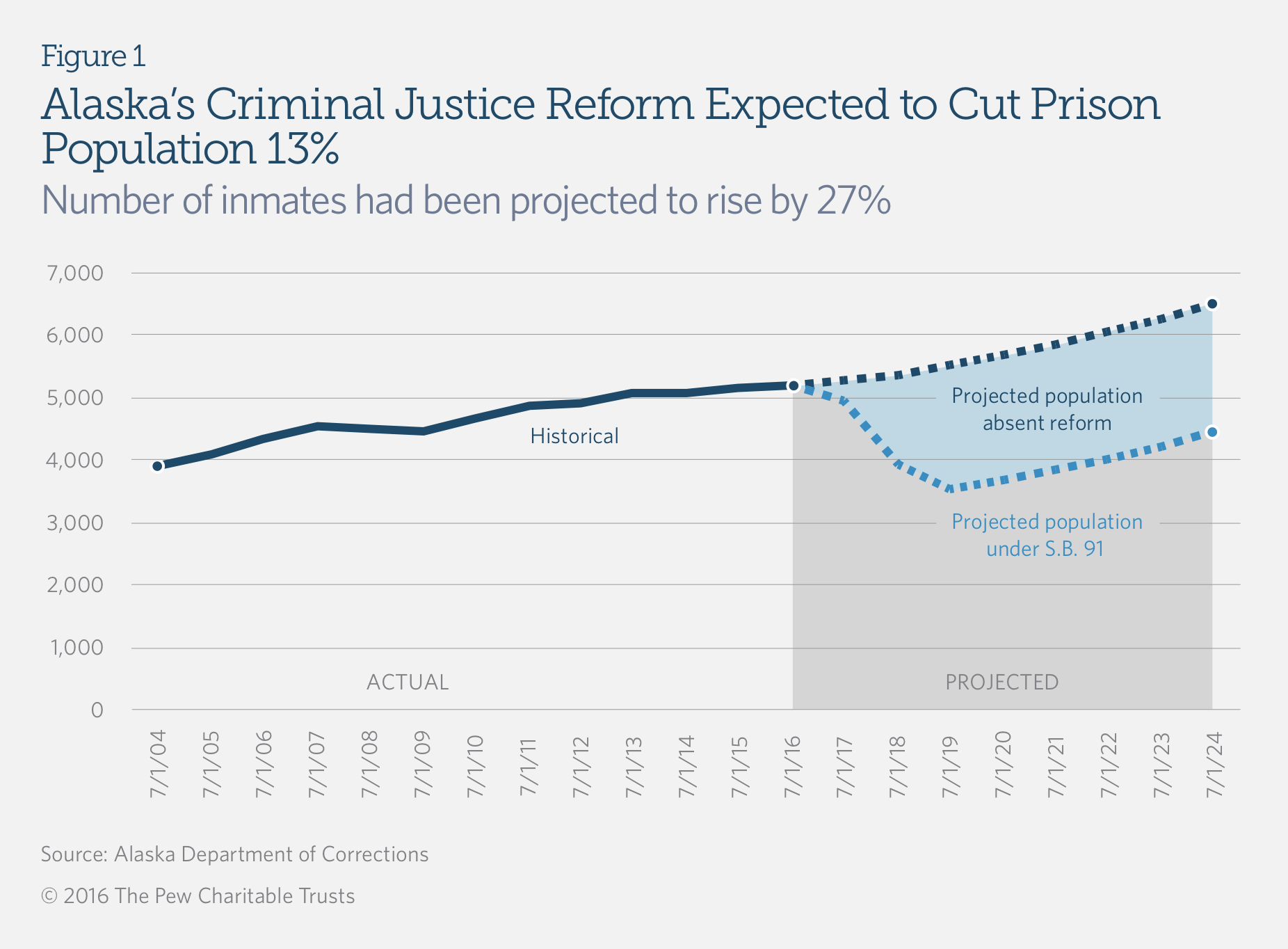

Alaska’s decision to end the reliance on money bail came at a time of widespread concern in the state about its skyrocketing incarcerated population and the subsequent costs. Between 2005 and 2014, the state’s jail and prison population increased 27 percent, nearly three times faster than overall population growth. The prison population’s growth was directly related to the widespread use of bail, according to research by the PEW Charitable Trust. In the same time period, the pretrial incarcerated population — people waiting in jail for court hearings after their arrests — increased 81 percent. In a study of five courts across the state, the Alaska Criminal Justice Commission and PEW Charitable Trust found that money bond was required in two-thirds of cases, with about 40 percent of bonds set at $2,500 or more. When high bail bonds were set, defendants were less likely to walk free and ended up spending longer durations behind bars than those with smaller amounts.

Meanwhile, the state’s correctional budget grew 60 percent over the same time period. It had to go so far as to open a new correctional center in 2012 that cost $240 million. Without any changes in state policies, the population of incarcerated people was set to grow another 27 percent by 2024, adding $169 million in costs. The growth would have required the state to reopen a closed facility and possibly build a new one.

With the new reforms in place, PEW estimates that the number of inmates will decrease by 13 percent and that the state will save $380 million. The state plans to reinvest $98 million of that total over six years in crime victim services, pretrial services and supervision, re-entry support, substance abuse and mental health treatment in both prison and communities, and violence prevention.

The new law that took effect at the beginning of the month didn’t just do away with bail; it also included other significant reforms. Law enforcement officers are now given greater latitude to issue citations for a number of low-level offenses with a summons to appear in court, rather than arresting people, thus diverting more people from jail in the first place. Defendants will now wait for shorter periods of time before their first court appearance; now they must appear before the court within 24 hours of arrest unless there are compelling reasons to delay it. And it prohibits the use of third-party supervision when defendants are released if pretrial services are available, while mandating that courts send defendants reminders at least 48 hours before required appearances.

Many — including those who might not be natural advocates of criminal justice reform — believe that both safety and fairness will be better served in the new regime. “Reducing our state prison population is vital to making conditions inside the facilities safer, both for prison inmates and correctional officers,” Department of Corrections Commissioner Dean Williams said when the bill was signed. It “will reduce unnecessary pretrial detention and also strengthen alternatives to prison for those convicted of nonviolent offenses.”

“This was an enormous achievement that will reduce recidivism, hold offenders accountable, and get the most public safety out of each dollar spent on our criminal justice system,” said Republican Senator John Coghill, a sponsor of the original law.

Alaska itself, a deeply red state, may not seem like a likely candidate for leading the charge on bail reform. But the issue has attracted supporters from disparate political stances. New Jersey’s Republican governor helped champion a law that ended bail in the state. Kentucky was an early adopter, directing judges to release all low-risk defendants beginning in 2011. Meanwhile, some deep blue states, such as California and New York, are still working toward reform.