Alabama Officials Executed Nathaniel Woods Despite Claims of Innocence. Then, Against His Religious Beliefs, They Autopsied His Body

‘It was almost like they were going to do whatever they could to demean him and take away his dignity,’ Woods’s spiritual adviser said.

It has been over two weeks since Alabama executed Nathaniel Woods, but his family’s grief has been compounded by the horror of what happened after his death against his final wishes.

Despite a frantic scramble by family, attorneys and supporters to stop it, the state of Alabama performed an autopsy on Woods’s body after the execution, something that is considered an outright desecration in the Islamic faith that Woods converted to near the end of his life.

“We did everything we could to try to stop them from cutting him open, but they didn’t care,” said Pamela Woods, Woods’s sister.

In the aftermath of his high-profile execution, this last act by the state felt intentionally cruel to those who cared about Woods and believed he did not deserve to die. Woods was convicted in the 2004 shooting deaths of three Birmingham police officers. He was not the shooter, but prosecutors convinced a jury that he planned the killings. Woods’ supporters firmly maintain that he was not responsible for the murders.

“He was mistreated in every way possible,” Imam Yusef Maisonet, Woods’s spiritual adviser, said.

Maisonet wrote a letter to warden Cynthia Stewart of Holman Correctional Facility on Woods’s behalf, requesting that the state not perform an autopsy because it was against Woods’s religious beliefs. He said he gave the letter to the warden’s secretary two days before the execution but never received a response.

The Alabama Department of Corrections (ADOC) would not confirm whether the warden received the letter.

“I feel like the request fell on deaf ears,” Maisonet said. “On top of killing him, it was almost like they were going to do whatever they could to demean him and take away his dignity. That was a real disgraceful way to treat a human being.”

The morning after Woods was executed, Pamela Woods, still numb with shock, called Holman Correctional Facility from her nearby hotel room to find out about picking up her brother’s body. She had been so confident that he would receive a stay of execution or clemency that she hadn’t made funeral arrangements.

“First, they said they didn’t know where he was,” Woods recalled.

She called back and was told her brother’s body had been sent to a coroner’s office in Mobile. Knowing her brother did not want an autopsy, Woods panicked. This set off a frenzied 45-minute effort by family members, attorneys, and advocates to try to stop the autopsy.

Woods’s boyfriend alerted attorney Lauren Faraino, who began calling other attorneys and advocates. Someone suggested she contact Escambia County District Attorney Stephen Billy, who under state law would order the autopsy for any in-custody death.

Faraino called Billy’s office repeatedly, telling them it was an emergency, but she was told Billy wasn’t available to take a call. She sent him an urgent email, asking him to stop the autopsy. After weeks of working unsuccessfully to stop Woods’s execution, Faraino felt weary with defeat and wanted badly to prevent one more loss for his family.

“It was just another example of cruelty on top of cruelty on top of cruelty,” Faraino said. “There was no reason to do an autopsy because they already knew they killed Nate.”

Pamela Woods was able to reach Rebekah Jones, operations director of the Mobile Medical Facility for the Alabama Department of Forensic Sciences (ADFS), where her brother’s body had been taken.

“I explained that it was against Nate’s religion and was against his family’s wishes,” she said. “My boyfriend spoke with her. My sister spoke with her. She kept saying it was just procedure and they had to do it.”

Reached by telephone, Jones told The Appeal that she could not comment, and referred inquiries to the central office of the forensic sciences department. The ADFS director, Angelo Della Manna, did not respond to several messages seeking comment.

As Faraino was preparing to file for a restraining order, she contacted Jones and explained that she needed to halt the procedure immediately.

“Ma’am, the autopsy has already been performed,” Jones said in a recording of the conversation that Faraino provided to The Appeal.

About an hour later, Billy responded to Faraino’s email with a letter that stated he stood by his policy to order autopsies on all executions and he had instructed the Department of Forensic Sciences to proceed in order to confirm Woods’s cause and manner of death.

“It is not my intention of changing my position on this matter and would appreciate you not contacting my office again regarding this issue,” the letter concluded.

It is unclear whether ADOC considered Woods’s request regarding the autopsy or communicated it to anyone. Responding to questions through email, a spokesperson would only say, “At the direction of the Escambia County District Attorney and consistent with Alabama law, the ADOC released the body of Nathaniel Woods to the Alabama Department of Forensic Sciences for the purpose of completing an autopsy.”

Alabama law designates district attorneys as the authority with the power to order autopsies, but the law does not explicitly require an autopsy in every execution. Alabama’s execution procedures, recently unsealed by a federal judge, state that after a lethal injection is complete, “the body will be placed in a body bag and onto a stretcher to be taken by van to the Department of Forensic Science for a postmortem examination.”

Woods converted to Islam on Feb. 25, nine days before his scheduled execution. His sister Pamela, who is not Muslim, supported his decision.

“He didn’t want to be a burden on his family, and he never was,” she said. “He was a giver his whole life. He had a good heart. I’m glad he converted to Islam because it helped him find peace.”

Woods wanted a Muslim funeral and to be buried in a Muslim cemetery. His family made both of those wishes happen, but he also asked to be buried in Mobile. His sister decided to have him buried in Atlanta instead, in a cemetery near her home so she can visit him often.

“There is no way I would bury my brother in the soil of the state that killed him,” she told me. “I know he would be OK with that.”

After the autopsy was complete, a Muslim funeral home received Woods’s body. Maisonet told The Appeal that in keeping with tradition, they washed and shrouded the body at the funeral home, then took it to a mosque in Mobile for funeral prayers. Later, Woods’s family viewed his body and took it to Atlanta.

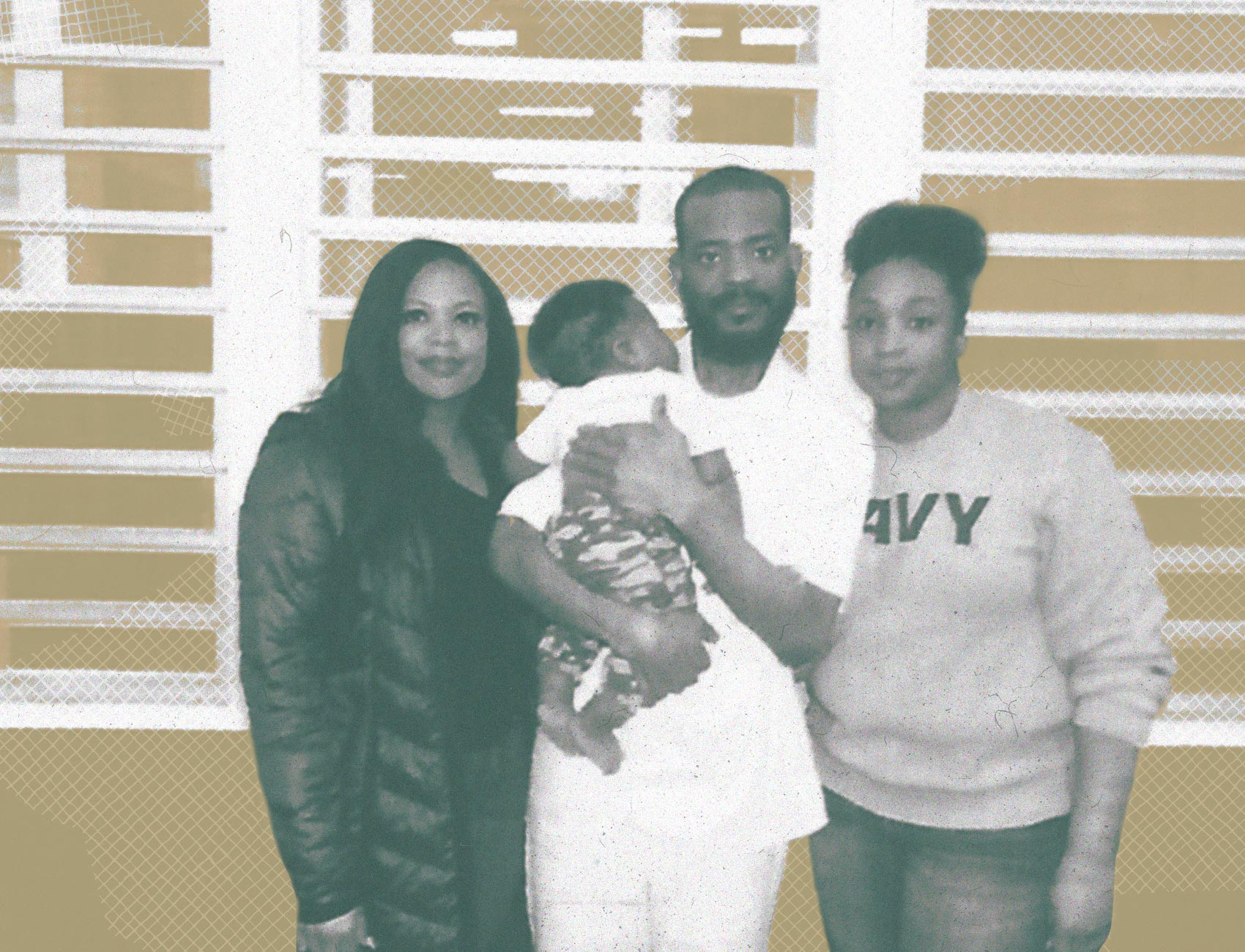

Pamela Woods said the whole ordeal felt unnecessarily hostile, like the state of Alabama was intent on hurting her family even beyond the end of her brother’s life. She finds comfort in that final family visit, when he got to see his daughter for the first time since he was sent to death row. He was able to hold his baby grandson for the first and only time, kissing his chubby cheeks.

Woods said her brother was happy and smiling in the last hours of his life, a bittersweet memory given the clinical coldness of his death and its aftermath.

“I will never feel OK about what they did to my brother,” Woods said. “It wasn’t enough that they killed him. They had to keep going.”