Dying Behind Bars: Another Form of Capital Punishment

Prisons are ill-equipped to handle their aging population, which has tripled in the past two decades.

This essay was published in partnership with Prison Journalism Project, which publishes independent journalism by incarcerated writers and others impacted by incarceration. Sign up for The Prison Journalism Project’s newsletter, or follow them on Instagram or Twitter.

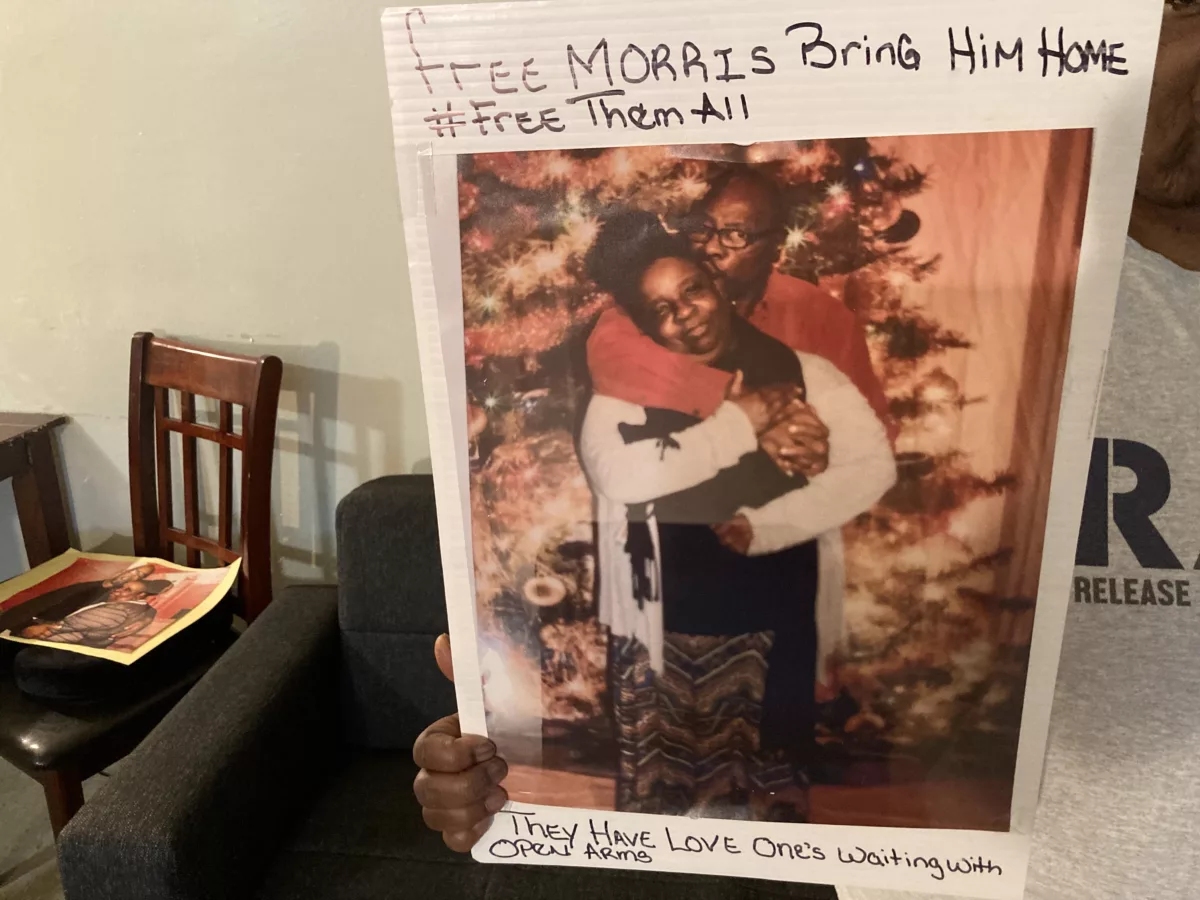

When Theresa Grady, 62, calls her husband in prison, she tries not to let her voice crack and does her best not to cry. Sometimes, though, her upbeat veneer fractures, she told The Appeal.

“I try to keep what they call a happy face, a smile, but sometimes I know he hears that tone in my voice,” Theresa said. “Sometimes I can’t hide it.”

Her husband, Morris Grady, started serving a 40-year prison term in 2007 after being convicted of robbery and attempted murder. At 68, Morris must serve at least 17 more years before he can see a parole board, and he’s already 11 years older than the average age at which incarcerated people die in New York state prisons, according to the COVID Behind Bars Data Project at the UCLA School of Law.

At this point, Theresa has learned to face the reality that she may never live with her husband again, even though he didn’t receive a life sentence. She feels increased urgency to try to gain her husband’s freedom, however, because he’s living with serious kidney disease and is not far from kidney failure. Theresa and Morris told The Appeal that Morris struggles to get consistent medical treatment in prison.

“He’s aging at a rapid speed inside,” said Theresa, who works as a community leader with the New York-based advocacy group Releasing Aging People in Prison. “His body movements are like an 80-year-old person.”

Morris says the most frustrating part of medical care in prison is that it is often delayed, and he sometimes has to file a grievance in order to receive treatment. He finds that the medical staff is “slow to act, unless they see blood,” he wrote to The Appeal via the prison’s online messaging service.

“I try to keep a positive outlook about my health, and continue to pray that I won’t meet my demise in prison,” Morris wrote. “That’s my greatest fear.”

A spokesperson for the New York State Department of Corrections and Community Supervision (DOCCS) told The Appeal in an email that the department cannot comment on the health or medical care of an individual in custody because of the HIPAA Privacy Rule, but said incarcerated people are provided “the community standard of care.”

“All DOCCS facilities have medical staff on site and, when medically necessary, individuals may be transported to a community hospital for emergency treatment or other medical service,” the spokesperson wrote.

Morris is one of hundreds of thousands of prisoners who are growing old in U.S. prisons and might die there. The country’s overall prison population peaked at roughly 1.6 million people in 2009. Though the overall number of incarcerated people has been decreasing ever since, the number of older people in prison has been increasing.

There were only 48,000 people aged 55 and older incarcerated in 2001, according to the federal Bureau of Justice Statistics. That number jumped to 154,000 by 2019, the most recent year for which data is available. This population also makes up a much larger share of prison deaths than it once did, going from 34 percent of total prison deaths in 2001 to 63 percent of deaths in 2019.

“It’s not like prisons are health-promoting spaces,” said Stephanie Grace Prost, an associate professor at the University of Louisville who researches health and aging in prisons. “Chronic health conditions are either generated or are exacerbated by the setting.”

Parole-reform advocates in New York, the Gradys’ home state, are pushing for legislation to help reverse this trend and decrease the number of older incarcerated people.

The Fair and Timely Parole Act, which was first introduced in 2017, would direct the New York State Board of Parole to “grant discretionary release unless the individual in question poses a current, unreasonable risk that cannot be mitigated by community supervision,” according to an emailed statement from the bill’s sponsor, Sen. Julia Salazar, a Democrat from Brooklyn.

“The Parole Board often denies parole due to the nature of the underlying crime of conviction,” Salazar told The Appeal in an email. “Little consideration is given to the time passed since conviction, whether the person has shown a drastic transformation during their time incarcerated, or whether they pose a risk of violating the law if released.”

Another piece of legislation, known as the Elder Parole Bill, which was first introduced in 2018, would make it so that New Yorkers aged 55 or older who had served at least 15 consecutive years in prison would get a parole hearing regardless of their minimum sentence. This bill would immediately make roughly 1,000 aging state prisoners, including Morris Grady, eligible for parole hearings.

“We must stop throwing all of our people—and all of our dollars—into these dungeons and instead invest in supporting people’s return to their communities,” Sen. Brad Hoylman-Sigal, a Manhattan Democrat who sponsored the Elder Parole Bill, told The Appeal in an email.

A 2021 Columbia University report found that 1,278 people had died in New York prisons in the preceding decade—more than the number of people killed in state executions during the roughly 370 years the death penalty was legal in New York. The report argues that long sentences are New York’s “new death penalty.

“If you can’t execute people through capital punishment, then you can do it through incarcerating them forever,” Melissa Tanis, a co-author of the report, said in an interview. “It’s a loophole that is used to exact punishment on people in a way that doesn’t recognize their humanity and capacity to change.”

Tough-on-crime policies gained popularity in the 1980s and ’90s, leading to a 550 percent increase in the country’s overall prison population by the mid-2000s. Long prison sentences became more common, and parole release rates dropped. Now elderly prisoners are suffering the potentially fatal consequences of those policies. They’re locked away until they die, even though they pose virtually no risk to public safety. The recidivism rate for people between the ages of 50 and 65 is slightly higher than 2 percent, and it’s close to 0 percent for those older than 65.

Theresa Grady, who has known her husband for close to 50 years, told The Appeal that Morris has changed for the better during his incarceration and has completed all of his required prison programs.

Each time she visits Morris in prison, she says, she sees the aging in his walk and in how he now forgets things and occasionally struggles to pronounce words—a far cry from the teenager Theresa grew up with in Harlem. If his kidney disease worsens, he’ll need dialysis three times a week, according to Theresa, who said prison staff told her over the phone that they won’t have enough staff to transport her husband to every dialysis session.

“What’s he supposed to do? Lay in his cell and die?” she said. “That’s the one thing he keeps telling me he doesn’t want to do.”

DOCCS told The Appeal that “patients requiring dialysis are either transported regularly to a dialysis treatment clinic or are transferred to a correctional facility that has a dialysis unit.” Three correctional facilities in New York—Wende, Elmira, and Fishkill—have on-site dialysis units that are maintained by DOCCS.

Theresa said that if Morris’ kidney disease worsens significantly, medical parole could be an option, but that route rarely works. Out of 1,049 medical parole requests submitted in 2020, only 18 were approved, according to New York State Focus.

“Most people with a medical clemency just about have to be dead to come out the door,” she said.

If he were to be released from prison, Morris would want to seek medical treatment for his kidney disease, get a job and a driver’s license, and take time to readjust to life outside, he told The Appeal. He said he wants to build a relationship with his family, go dancing with his wife, and get a puppy that he and Theresa can take on long walks.

Without legislative or judicial intervention, however, Morris and Theresa are unlikely to reunite outside the prison walls.

“I try to fight through it, but sometimes I break down in tears,” Theresa said. “I don’t tell Morris, because I don’t want him worrying.”

More than anything, she said, elderly incarcerated people want what everyone wants—to spend their final years, and days, surrounded by family.

“Most of them just want to come home, sit down, and enjoy the last of their time with everybody,” Theresa said. “I’d rather Morris die at home than die in his cold cell by himself.”