Advocates Fight Texas Statute Delaying Transgender Prisoners’ Ability to Change Their Names

Marius Mason is a transgender man incarcerated at FMC Carswell, a federal women’s prison located in Fort Worth, Texas. Since at least 2014, Mason has wanted to change his legal name to his chosen name, an important step in the transition process for many transgender people. Section 45.103 of the Texas Family Code, however, prevents anyone […]

Marius Mason is a transgender man incarcerated at FMC Carswell, a federal women’s prison located in Fort Worth, Texas. Since at least 2014, Mason has wanted to change his legal name to his chosen name, an important step in the transition process for many transgender people.

Section 45.103 of the Texas Family Code, however, prevents anyone in Texas with a felony conviction from changing their legal name until two years after completing all of the terms of their sentence. For Mason, whose expected release date according to the federal Bureau of Prisons is October 2027, that means being forced to answer to his legal name whenever he uses the phone, receives a letter, or is called by correctional officers over the intercom which he says exacerbates the gender dysphoria he struggles with every day.

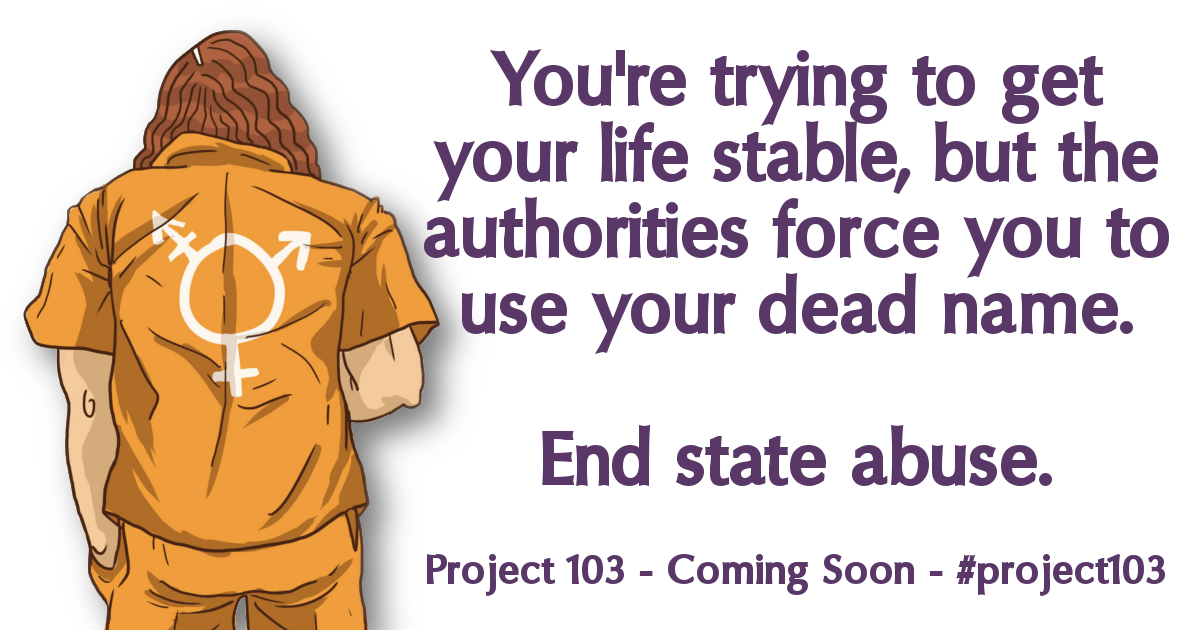

It’s a statute that advocates have recently set out to change. On March 28, the Texas-based Trans Pride Initiative, along with the Austin Community Law Center and New York City-based civil rights attorney Moira Meltzer-Cohen, announced their intention to challenge the constitutionality of Section 45.103, which they say violates the rights of transgender inmates. The lawsuit will be filed in federal court in Texas on behalf of Mason and two other transgender prisoners housed in federal facilities in Texas.

“For transgender persons, [this statute] extends the term of their sentence by two more years, and places cruel and unnecessary barriers in the way of gaining stability on release,” Nell Gaither, president of the Trans Pride Initiative, said in a statement. “We need to eliminate barriers for trans persons trying to survive, not make issues harder by tacking on additional punishment.”

Advocates argue that denying trans people the right to change their legal name, or the gender marker on their identity documents, poses substantial barriers to their safety and well-being. For currently incarcerated trans people, the continued use of their birth name by guards and other prison officials may contribute to a climate of violence and harassment. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, one-third of trans prisoners have experienced sexual violence while incarcerated, the highest rate of any demographic group studied.

Subsection 103 of the Texas Family Code also impedes trans people from re-integrating into society once they’re released. Trans people who do not have identification that matches their chosen name or gender identity may encounter significant difficulties with law enforcement if, for example, they are asked to present a driver’s license during a traffic stop. And trans persons who are unable to change their identity documents may be forcibly outed when engaging in activities crucial to their survival, such as renting an apartment or accessing medical care.

The prohibition on name changes in the Texas Family Code may also violate a prisoner’s right to medical care by impeding access to a healthcare necessity. In a policy statement, the World Professional Association for Transgender Health maintains that the ability of transgender people to change their name or gender marker on their identity documents is medically necessary.

“According to the medical research done with trans people both in and out of institutional settings, the effects of having a legal names that do not reflect trans people’s gender identities are deeply detrimental,” Ronica Mukerjee, a family nurse practitioner and director of the New York-based Transgender Health Services for Community Healthcare Network, told The Appeal, in an email. “In order to avoid suffering and cruelty, which clearly lead to anxiety, depression as well as suicidal ideation and attempts, trans prisoners should always be allowed to use a name that reflects their true gender identity.” Similarly, a recent Journal of Adolescent Health study found that transgender youth who were able to use their name in most facets of their everyday lives experienced 71 percent fewer symptoms of depression and a 65 percent decrease in suicide attempts.

“The issue is not that being trans is a mental health risk or condition,” civil rights attorney Meltzer-Cohen told In Justice Today in an email, “but that the lack of access to gender affirmation can give rise to mental health problems where none would otherwise exist.”

Courts are increasingly recognizing that transgender people have a constitutional right to gender-affirming care. In April 2015, Jon Tigar, a federal judge in the Northern District of California, ruled that the state violated the Eighth Amendment right to medical care of transgender prisoner Michelle Norsworthy by refusing to provide her with sex reassignment surgery. California has since begun to offer gender-affirming surgeries to incarcerated people.

The organizations and attorneys seeking to overturn Section 45.103 have dubbed their effort Project 103 and are currently fundraising to cover the estimated $5,000 that will be necessary to cover court-filing fees and other related costs. As the initiative gets off the ground, Mason waits for the day when he is no longer referred to by his birth name.

“[M]y old [name] reminds me every day of the person that I am not anymore,” Mason said in a statement released by Project 103, “and it feels false and humiliating to be constantly reminded that society does not see me as the man I want to be. It feels cruel to me to force me to live in this way.”