A Virginia Prison Held A Man In Solitary Confinement For Over 600 Days

Virginia’s Department of Corrections has recently settled two lawsuits over its use of solitary confinement—a practice lawmakers are moving closer to abolishing.

Within two months in solitary confinement at Virginia’s Red Onion State Prison, Tyquine Lee began to speak in numbers. He signed his name with a series of random letters.

During his more than 600 days in isolation—from 2016 to 2018—he lost more than 30 pounds. His food was sometimes covered in maggots, dirt, and insects. He was confined to his cell for 22 to 24 hours a day. When he voiced grievances about his treatment, correctional officers maced him—about 25 times in total, according to a suit filed in 2019 by his mother against the Department of Corrections.

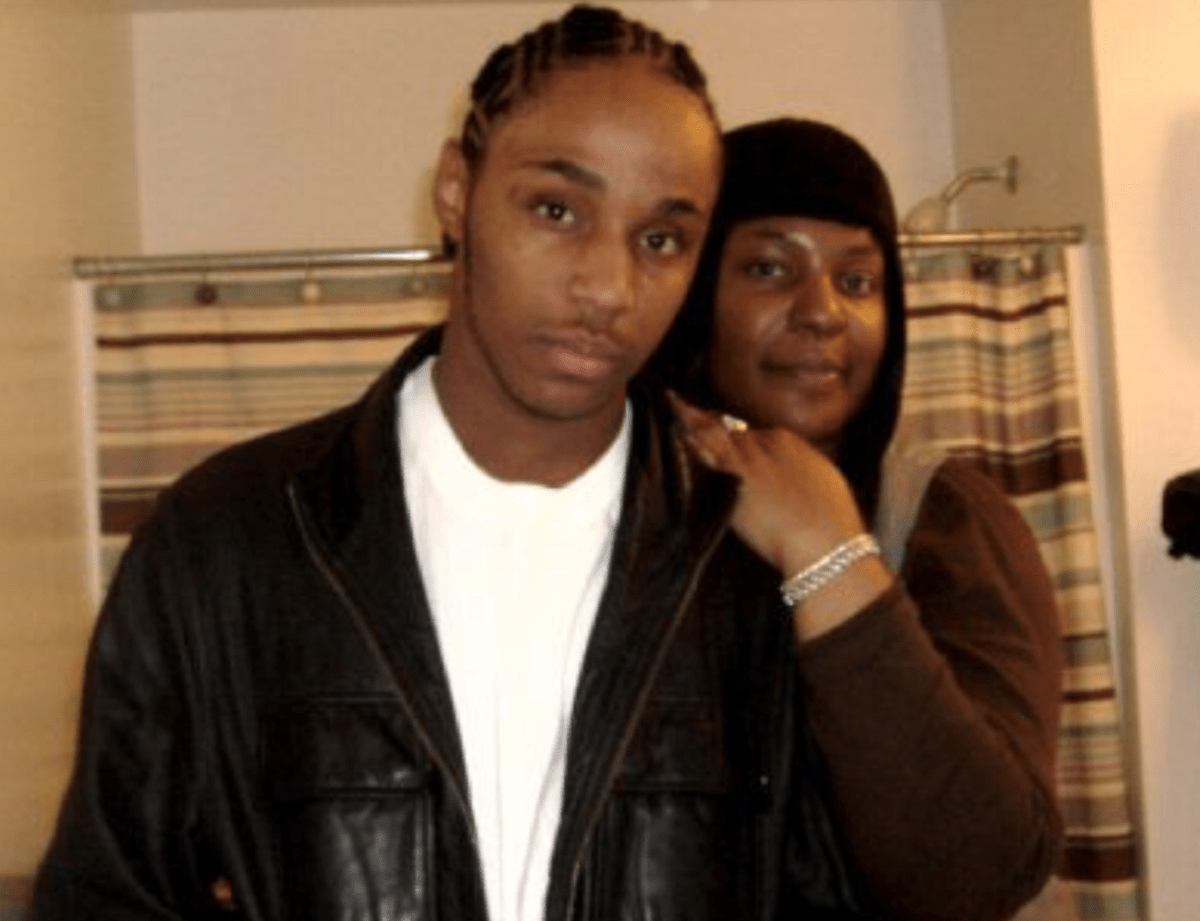

“When I actually got to go visit him I saw someone that wasn’t my son. He was just so small,” Lee’s mother, Takeisha Brown, told The Appeal. “He was rambling in numbers. He had a language of his own.”

In prison parlance, solitary confinement can be called administrative segregation, protective custody, the SHU (Special Housing Unit), or restrictive housing. But its features are largely the same: confinement in a cell, typically the size of about a parking space, for at least 20 hours a day. Its damage is fairly universal as well, with numerous studies finding it causes physical and emotional deterioration.

For those with a history of mental health conditions, like Lee, solitary confinement is particularly devastating. Between the ages of 8 and 10-years old, he was hospitalized four times for behavior related to mental health challenges, according to his mother’s lawsuit, filed by the MacArthur Justice Center and pro bono attorneys from the law firm Williams & Connolly.

Lee’s deterioration while in solitary confinement was detailed in mental health progress notes.

Less than two months after he was placed in solitary confinement, on July 21, 2016, a mental health progress report stated that when Lee was asked if he was suicidal or homicidal, he “began naming various numbers over and over.” But the next day the psychologist noted that Lee was not exhibiting symptoms of mental illness because he “verbally engage[d] the clinician.”

More than a year later, in September of 2017, a psychiatrist reported in his notes that Lee was communicating in “gibberish and numbers.” Lee’s behavior, he wrote, “cannot yet be separated from malingering.”

But despite documentation of his deteriorating condition, no actions were taken to move him until January of 2018, when the Institutional Classification Authority, which monitors prisoners’ progress in solitary confinement, recommended a transfer to another prison, where he received inpatient psychiatric care, according to the MacArthur Justice Center.

Last month, Lee, now 28-years-old, was transferred again, this time to a prison in New Jersey, near his mother’s home, as part of a settlement agreement reached in October between Brown and Virginia’s Department of Corrections.

The use of solitary confinement in Virginia has been the subject of extensive litigation, media coverage, and legislative activity. Today, a state bill to effectively end long-term solitary confinement in prisons passed the Senate. Virginia legislators are also considering bills to abolish the death penalty and to give people in prison the right to vote.

“We’re in this fight until we win this fight,” said David Smith, chair of the Virginia Coalition on Solitary Confinement. “This is the first time we’ve actually had a bill get to the Senate floor that would effectively end the use of extended solitary confinement in Virginia.” The bill, said Smith, will now be referred to a committee in the House of Delegates.

Smith said when he was incarcerated at Norfolk City Jail, he was kept in solitary confinement for approximately sixteen months. “I lost my senses to the point where I would have conversations with the TV,” he said. “I lost my will to fight to live, to really fight for myself.”

Department of Corrections spokesperson Lisa Kinney told The Appeal they cannot comment on the settlement agreement with Lee and they have not taken a position on the bill. The only facility in Virginia with “long-term restrictive housing” is Red Onion State Prison, according to Kinney. There were 48 people in long-term restrictive housing at the facility as of Monday, she said.

“All inmates in restrictive housing are provided the opportunity to participate in a minimum of four hours of out-of-cell activity, seven days a week,” Kinney wrote in an email to The Appeal. According to Kinney, the status of people in restrictive housing is routinely reviewed by a multidisciplinary team of “facility leaders, including security, medical, mental health, and treatment.”

However, the department’s restrictive housing policy does not mandate four out-of-cell hours per day. The policy states, “Each institution should strive to confine offenders to their cells for less than 22 hours per day in restrictive housing units.” Kinney told The Appeal that the practice of offering prisoners in restrictive housing four hours outside their cells “has not made its way into the operating procedure yet” and that the written procedure will be “updated soon.”

“VADOC facilities were instructed in 2019 that effective no later than January 6, 2020, each inmate in any restrictive housing unit would be provided the opportunity to participate in a minimum of four hours out of cell activity, seven days a week,” Kinney said.

In the last six months, the Virginia Department of Corrections has settled two lawsuits over its use of solitary confinement, both requiring payouts of more than $100,000—to Lee and to Nicolas Reyes. On January 15, the Department of Corrections settled with Reyes, who was held in isolation at Red Onion for more than 12 years. Reyes, who does not speak or read English, could not complete the Department of Corrections’ step-down program, which is, generally, required for release from solitary confinement. The program materials were only offered in English.

The program was challenged in a lawsuit filed in 2019 on behalf of prisoners held in solitary confinement at Red Onion and Wallens Ridge state prisons by the ACLU of Virginia and law firm White & Case. The plaintiffs alleged that the program has trapped people in solitary confinement for years.

As part of the step-down program prisoners are required to complete workbooks and are evaluated on their hygiene, the neatness of their cells, and their rapport with staff and prisoners, according to the ACLU suit. If a unit manager determines a person is non-compliant, they can be made to restart the program, according to the ACLU suit. The Department of Corrections has filed a motion to dismiss, which the court has not yet ruled on.

The ACLU has also argued that the longer a person is in solitary, the harder it is to comply with the program’s requirements. In Lee’s case, his declining mental health prevented him from completing the program, according to his mother’s suit. “[Lee] attempted to complete the first two journals before his mental illness became so severe that he could not continue,” reads his mother’s complaint.

“I was asking, ‘Why are they keeping him in solitary confinement so long?’ and they said he had to remain there until he was able to complete their step-down program,” Brown told The Appeal. “I said, ‘He’s talking in numbers so how do you believe he’s going to complete something like this?”

UPDATE: This article has been updated with clarification about discrepancies in the written restrictive housing procedure from the Virginia Department of Corrections.