A Troubled Federal Prison Unit Gets New Life In A Different State

Instead of changing its conditions and practices, The Bureau of Prisons is simply moving a problem-plagued federal prison unit in Pennsylvania to Illinois.

On Feb. 3, 2011, staff at Pennsylvania federal prison USP Lewisburg’s Special Management Unit told Sebastian Richardson to “cuff up” and accept a new cellmate. Richardson was terrified; the man with whom he was about to share the cell, known as “The Prophet,” had attacked over 20 cellmates. The Prophet had just been released from hard restraints, a combination of metal handcuffs, ankle shackles, and a chain that encircled his chest. He was also, according to Richardson, ”rocking back and forth in agitation as he waited outside” the cell door.

Richardson refused to submit to being placed in handcuffs or accept his new cellmate. So a lieutenant and a Use of Force team member took him to a laundry area where he was stripped, put into paper clothes, and placed in hard restraints that made him scream in pain. He was then placed in a cell with another man who was also in hard restraints.

Three days later, Richardson was moved to another cell, again with another man in restraints. That man, Richardson later said, “was pleading for help because of the pain caused by the restraints. He stated that he could not breathe because of the chest chain and he could not feel his hands because of the tight handcuffs.”

On Feb. 10, Richardson was placed in four-point restraints, in which a person is shackled to a bed. He spent over eight hours this way and his requests to use the bathroom were denied, causing him to urinate on himself. Richardson was then placed in hard restraints for another 13 days.

By Feb. 23, Richardson had spent 20 days in restraints. He was allowed a shower, his first in weeks. Then, staff attempted to give him another dangerous cellmate. Richardson refused and was once again placed in restraints. Richardson spent a total of 28 days in restraints, with 15 different cellmates, all in hard restraints “applied in the same painful and torturous manner.”

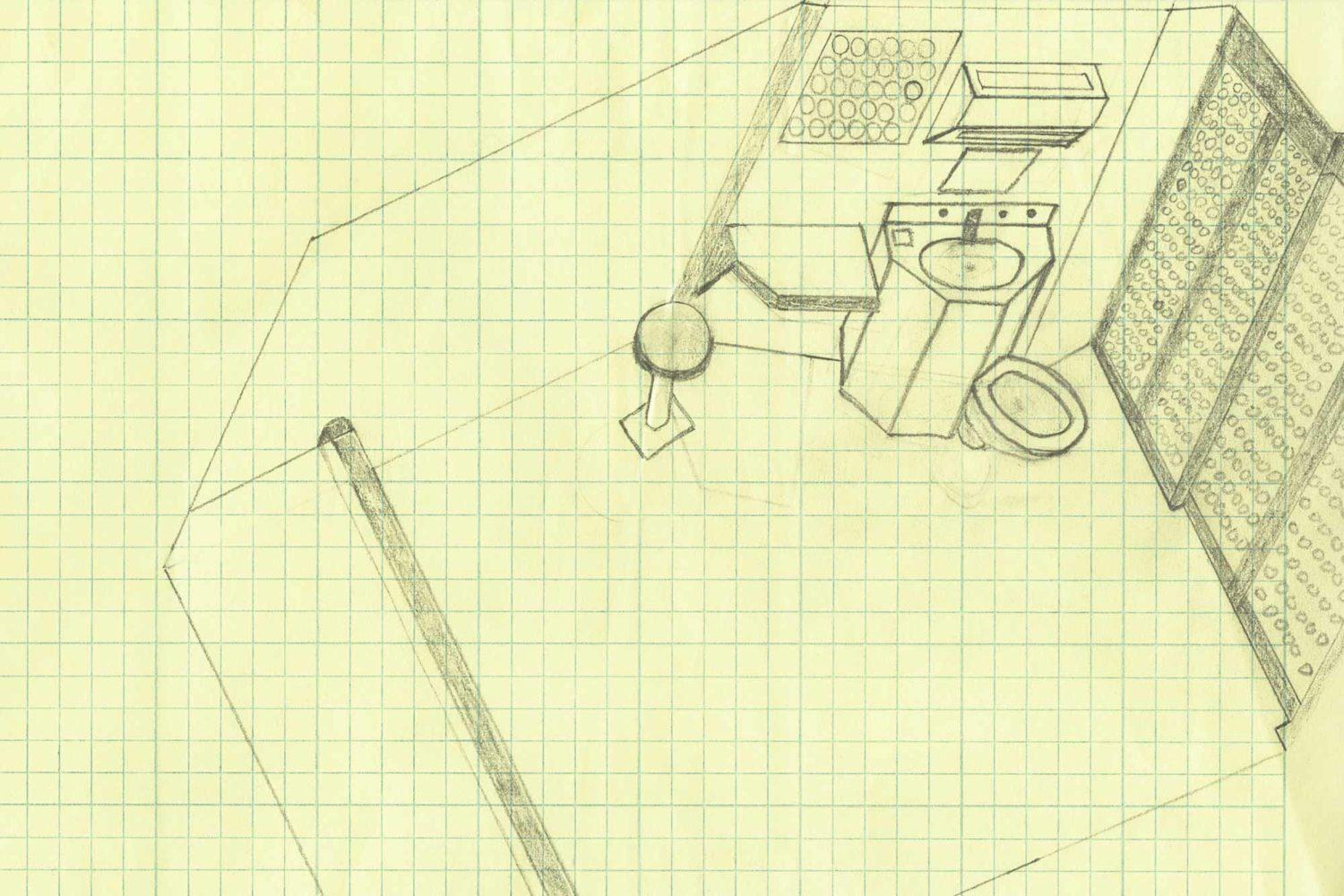

Since its opening in 2008, USP Lewisburg’s Special Management Unit—or SMU—has been hit with civil rights lawsuits challenging its treatment of people with mental illnesses and its use of restraints as punishment. In 2011, Richardson sued the Bureau of Prisons, which operates USP Lewisburg, over his conditions of confinement. In 2017, SMU prisoners Jusamuel Rodriguez McCreary, Richard C. Anamanya, and Joseph R. Coppola sued the Bureau of Prisons alleging that they were among dozens of men with serious mental illnesses who were denied adequate mental health care. “Men bang on the walls of their cells” in the SMU, according to the lawsuit, “they refuse to leave their cells for months, even for a shower; some men mutilate their bodies with whatever objects they can obtain; others carry on delusional conversations with voices they hear in their heads.” That same year, the Office of the Inspector General sharply criticized the prison’s mental health treatment as well as its deteriorating physical condition. (It was was built in 1931.) SMU cells, for example, are about 58 square feet, far smaller than the 80 square foot minimum recommended by the American Correctional Association. Also in 2017, the District of Columbia Corrections Information Council, a prison monitoring organization, visited Lewisburg and found that staff continued to use restraints, resulting in injuries to incarcerated people as well as a lack of access to emergency call buttons, programming, and mental health services.

As of August 20th, Lewisburg’s SMU houses approximately 830 people who are there due to a history of violence or participation in gangs. They are expected to complete three levels of programming within one year, all as they are locked in their cells for 23 hours a day.

Solitary confinement is typically defined as the practice of isolating people in cells for 22 to 24 hours per day. According to statistics compiled by Solitary Watch, 80,000 to 100,000 incarcerated persons are held in some form of isolated confinement. Though SMU prisoners are locked down all but one hour of the day, the Bureau of Prisons claims that “solitary confinement does not exist” in the federal prison system and considers placement in the SMU to be “non-punitive.” It’s a rosy characterization roundly rejected by criminal justice advocates, incarcerated people, and reporters alike; “USP Lewisburg might be the worst place in the federal prison system,” Justin Peters wrote in Slate in 2013, “so bad that some inmates there actually dream of being transferred to the famously isolating Supermax facility in Florence, Colorado.”

But instead of changing the conditions and practices of the Lewisburg SMU, the Bureau of Prisons announced in June that it will simply move it to a “state of the art maximum-security prison” in Thomson, Illinois. The Bureau of Prisons purchased the facility from the state of Illinois in 2012; state budget cuts have kept the nearly 20-year-old Thomson largely empty. “The Special Management Unit (SMU) at AUSP Thomson will operate in accordance with BOP Program Statement 5217.02 ‘Special Management Units,’” a BOP spokesperson wrote in an email to The Appeal. (The BOP declined to comment on the Richardson lawsuit.)

But advocates say that it’s the SMU model—not its location—that’s the problem.

Dave Sprout, a paralegal with the Lewisburg Prison Project, an advocacy organization focused on Central Pennsylvania’s prisons, says that the 23-hour daily lockdown in the SMU is detrimental to the mental health of prisoners and dangerous. He notes that the men spend their one hour out of cell in a recreation cage and they can be alone or among others, which increases the risk of attack and assault. As a result, many decline their one hour out of cell.

Back in their cells, many of the SMU’s prisoners are placed with cellmates, a practice known as double-celling. “Most of the problems we’ve seen [at Lewisburg] comes from being double-celled,” Sprout told The Appeal. Double-celling has led to fights, attacks and even deaths. From 2008 until July 2011, Lewisburg’s SMU had 272 reported incidents of violence. Between 2010 and 2017, at least four men at Lewisburg were killed by their cellmates. A culture of violence inside the Bureau of Prisons also means that many prisoners end up facing the federal death penalty. In June, two federal prisoners were sentenced to death for murdering another prisoner at USP Beaumont in East Texas. It appears that the practice of double-celling will continue at Thomson; a BOP spokesperson told The Appeal that two beds are provided in each cell there.

The opening of Thomson as an SMU has been applauded by U.S. Senator Dick Durbin, a Democrat, as a job creator for the northern part of Illinois. Durbin’s support contrasts sharply with his prior stances on solitary confinement, including leading the first Congressional hearing on solitary in 2012. In April, Durbin introduced a federal bill to limit the use of solitary confinement. Durbin’s office did not respond to The Appeal’s request for comment.

By the end of the year, the BOP will begin transferring people from Lewisburg to Thomson with warden Donald Hudson, who was the associate warden at USP Lewisburg, at the helm. Richardson’s lawsuit names Hudson as one of the defendants, alleging that Hudson was “responsible for custody and security at the institution, including decisions involving cellmate and recreation cage placements and the use of restraints.” Advocates and attorneys say the move will merely shift the SMU’s problems to another state. “History has shown that supermaxes are destructive failures, torturing everyone housed in them,” Deborah Golden, who represented Richardson in his 2011 lawsuit and is now an attorney at the Human Rights Defense Center, told The Appeal. “Housing people in unconstitutional conditions is unconstitutional, no matter the state.”