A Precarious Time For The Insanity Defense

Spotlights like this one provide original commentary and analysis on pressing criminal justice issues of the day. You can read them each day in our newsletter, The Daily Appeal. This week, Rolling Stone published a harrowing portrait of how one state’s enlightened approach to mental health and criminal behavior came to be threatened by one case that went […]

|

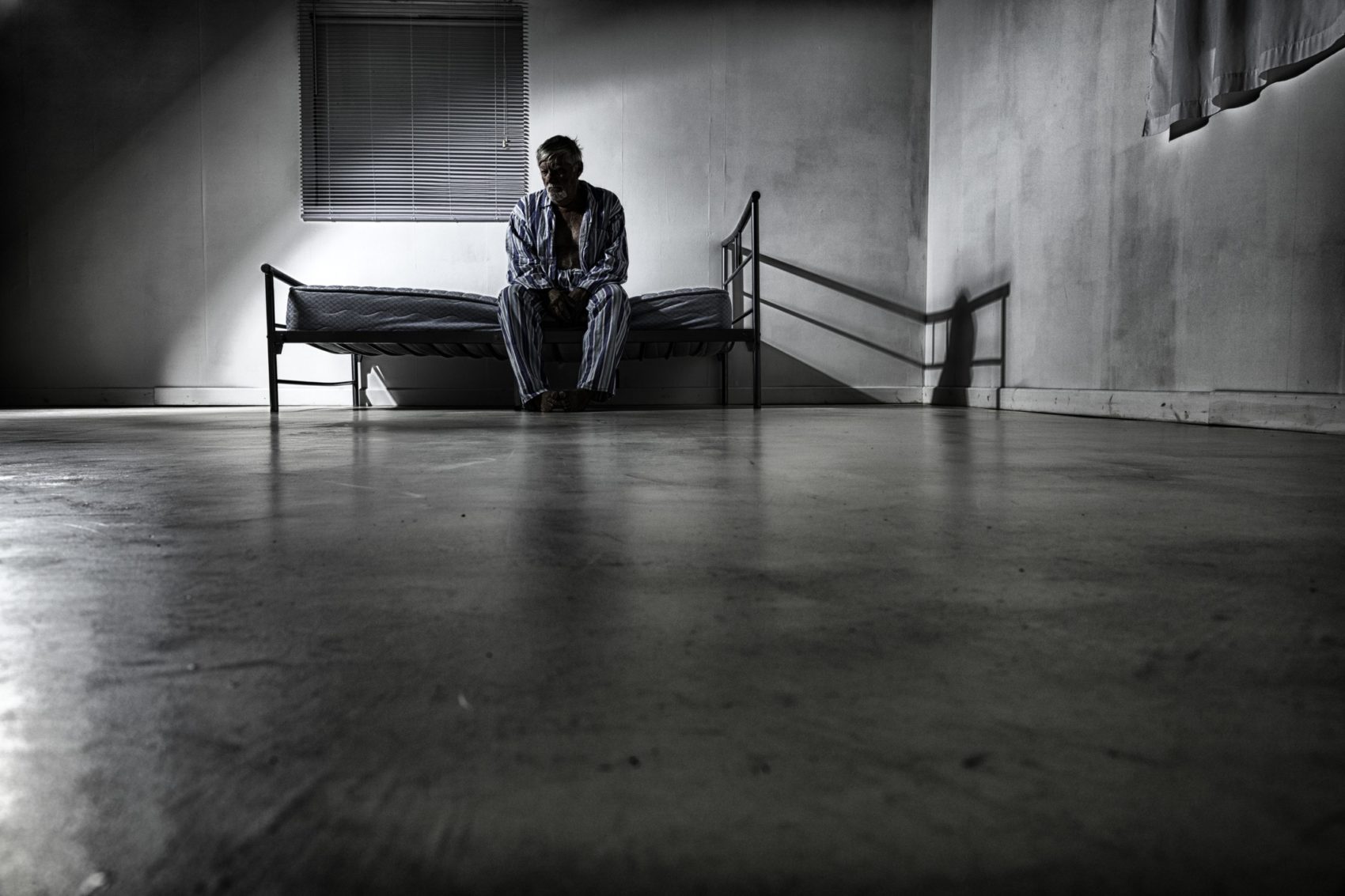

Spotlights like this one provide original commentary and analysis on pressing criminal justice issues of the day. You can read them each day in our newsletter, The Daily Appeal. This week, Rolling Stone published a harrowing portrait of how one state’s enlightened approach to mental health and criminal behavior came to be threatened by one case that went tragically wrong. Rob Fischer tells the story of Anthony Montwheeler, who, at 49 years old, kidnapped and killed his ex-wife while witnesses watched and tried to stop the stabbing. Montwheeler was not unknown to authorities: Two decades earlier he had kidnapped, but did not kill, a previous wife and their toddler. He was found “guilty except for insanity,” so he was not sent to prison, but placed under state jurisdiction for 70 years. “Here we are 20 years later,” says Les Zaitz, the publisher of the Malheur Enterprise, which has covered Montwheeler’s story. “Very quickly the question becomes, ‘What’s this guy doing loose in Malheur County?’” A lot of people have been asking this question. The answer can either be that something went wrong in this case, or something is wrong with the way the state treats mental illness. For the fearmongering set, the answer is the latter. Many wanted to know why all these patients weren’t simply in prison. But Fischer’s painstaking reporting and research indicates that the former is a far more reasonable response. In the 1960s, after the nation was alerted to inhumane conditions in many psychiatric hospitals, President John F. Kennedy did what politicians tend to do best: He tore down one system but failed to replace it with another. Deinstitutionalization decreased the population of people in state psychiatric hospitals from 559,000 in 1955 to 154,000 in 1980. There are now fewer than 43,000. Kennedy vowed that the “cold mercy of custodial isolation,” would be “supplanted by the open warmth of community concern and capability,” but the second part of that vision never materialized. Under President Ronald Reagan, federal funding for community mental health care was slashed. “Police officers became the nation’s front-line mental health workers,” Fischer writes. “In most jurisdictions, an arrest is the quickest way for an individual to receive mandatory care.” “Oregon, in its own small way, attempted something different,” Fischer continues. In 1977, it created the Psychiatric Security Review Board (PSRB), a group outside the prison system that provides regular case-manager check-ins, drug and alcohol screenings, subsidized housing, mental health care, and work placement for people acquitted by reason of insanity. Less than half of the people under the PSRB’s jurisdiction are in the state hospital. This means that many suffering from mental illness who have not been accused of a crime are receiving far less care. Even though most of the people under PSRB oversight have been charged with serious crimes, including kidnapping, rape, and murder, they rarely commit another act of violence once under state supervision. The board estimates that the recidivism rate for those on conditional release is around a half percent. A recent evaluation of post-conviction mental health care in the U.S. gave Oregon, along with three other states, the highest ranking. “But if Oregon’s PSRB had been something of a bright spot in an otherwise dismal picture of mental health care in the U.S., the case of Anthony Montwheeler underscored everything the public typically distrusts about insanity acquittals.” Montwheeler seems to have exploited a loophole in the system by claiming, after being placed in a state hospital following an arrest for theft, that he was not mentally ill and never had been. Plenty of people undergoing psychiatric care make such claims, but in this case, the claim was backed up by some clinicians’ assessments as well. Oregon’s jurisdiction over psychiatric patients in criminal and noncriminal cases, is allowed as long as a person continues to suffer from certain severe mental illnesses and he or she is a danger to the public. Although some evaluations concluded that he could be a danger, the review board ultimately decided that he should be discharged because the first prong was not met. Does the subsequent murder mean that Monwheeler was, in fact, mentally ill all along, or that he had gamed the system and committed more crimes? If it’s the latter, why wait three years to commit the crime, and do so in front of so many witnesses? Should the system be upended, or tweaked, or should it remain the same, with the understanding that its track record is still stellar, despite this aberration? The Malheur Enterprise earned a grant from ProPublica and ran a series called “A Sick System: Repeat Attacks After Pleading Insanity,” suggesting, falsely, that the PSRB was endangering the public. One piece, citing statistics, claimed to show that “people freed by Oregon officials after being found criminally insane are charged with new felonies more often than convicted criminals released from state prison.” But last January, after a reader prompted a review of the reporting, ProPublica posted a devastating series-wide retraction. The review found that the coverage had, in Fischer’s words, “dramatically overestimated the frequency with which people discharged by the PSRB committed new felonies—in fact, the recidivism rates of offenders released from prison were much higher.”

Even if Oregon’s system remains in place, however, it will still be true that the vast majority of people who suffer from mental illness are treated by the criminal system as if they are in perfect control of their actions. I have represented clients who were clearly having psychotic breaks during certain illegal actions, and I have been met with the same meaningless line from prosecutors: “He needs to be held accountable for his actions.” But what can accountability even mean when a person has no recollection of ever violating the law, and, after treatment, returns to his calm, law-abiding self? What can putting that person in prison possibly do? It will, of course, increase the chances that corrections officers, trained to get prisoners to submit to authority rather than treat mental illness, will beat my client, throw him into solitary confinement, or worse. But will it engender accountability? Safety? Justice? Regardless of whether Montwheeler suffered from a qualifying mental illness, he was 6 years old when his father murdered his mother. This fact alone would never qualify him as insane, but surely it had an impact on his development, and most likely played a role in his subsequent behavior toward intimate partners. Instead of broadening their definitions of what qualifies as diminished capacity or insanity, or interrogating how we respond to such people before and after they harm others, many states have gone in the other direction, eliminating the already near-impossible standard of insanity. In the first argument of this term, the U.S. Supreme Court considered whether states may abolish the insanity defense, examining the case of James Kahler, who was sentenced to death in 2011 for killing four family members. His lawyers said he had such severe depression that it was impossible for him to understand reality or to distinguish right from wrong. But because Kansas eliminated the insanity defense about two decades ago, Kahler was barred from raising this defense. According to the New York Times, Sarah Schrup, a lawyer for Kahler, said that was a radical departure from American legal traditions. “For centuries,” she said, “criminal culpability has hinged on the capacity for moral judgment, to discern and to choose between right and wrong. The insane lack that capacity.” Kansas, Idaho, Montana, and Utah have all abolished the insanity defense, although defendants in those states may still argue that they lacked the required intent to commit the crime with which they were charged. Justice Stephen G. Breyer pointed out that this means that people are not culpable if they truly did not know what they were doing (if, for instance, they killed a human being under the delusion that they are killing a dog). But they are culpable if they do not know that their actions are wrong (if, for instance, they knew they were killing a human but believed a dog told them to kill a that human). “What’s the difference?” he asked. “It’s quite deep, this question.” Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. showed a lack of understanding about mental illness, one that is shared by many Americans. He said that Kahler’s actions did not appear to be those of an insane person. “This is an intelligent man,” Justice Alito said, as if intelligence were impossible for a mentally ill person. “He sneaked up on the house, where his wife and her mother and his children were staying. He killed his ex-wife. He killed her mother. He executed his two teenage daughters. One of them is heard on the tape crying. He, nevertheless, shot her to death.” This is evidence of extreme cruelty for a sane person, but what does it mean for an insane person? “All acts of extreme violence, on some level, seem insane,” writes Fischer. “But under the law, there is a sharp distinction between mental illness” and personality disorders, such as psychopathy, “which manifest in traits like a lack of empathy, a transactional nature, [and] emotional volatility.” “What we don’t want is the insanity defense to be redefined where there’s this influx of new diagnoses,” one mental health official told Fischer. Personality disorders are excluded, she added, without explanation, “because those folks—that’s who the prison system is for.” One crucial distinction between a condition like schizophrenia and a personality disorder like psychopathy is that more effective treatments exist for the former group of people. But the existence of such disorders, the fact that they influence people’s behavior, does not depend on our ability to cure them, nor does it depend on whether we as a society decide to condemn the people afflicted by them as criminals or treat them as patients. This is what the American Psychiatric Association argued in its amicus brief in the Kahler case. “Amici take no issue with the view that the question presented is a legal and moral issue,” they write. “At the same time, a scientific understanding of mental illness and its effects lends weight to the arguments in favor of recognition of the insanity defense as constitutionally required.” One of the first things law students learn in criminal law class is that a person whose body is used as a projectile by another person to cause harm cannot be criminally prosecuted. This seems intuitive to most students. But somehow, if a person’s body is controlled by a mentally ill brain, not another person, it no longer makes sense. A scientific understanding, not panicked moralizing, would indeed be a good place to start. |