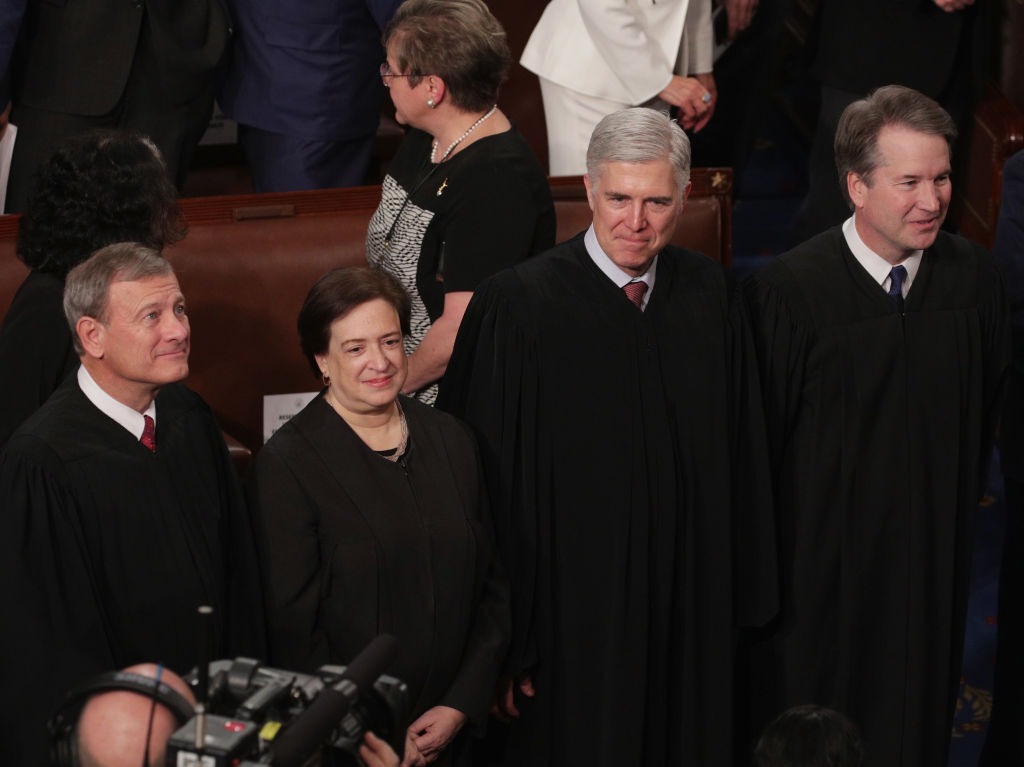

A Discriminatory Rule Even Justice Kavanaugh Opposes

Spotlights like this one provide original commentary and analysis on pressing criminal justice issues of the day. You can read them each day in our newsletter, The Daily Appeal. This week, the Supreme Court appeared ready to rule against convictions by nonunanimous juries. The Court heard arguments in Ramos v. Louisiana, a case that challenged the […]

|

Spotlights like this one provide original commentary and analysis on pressing criminal justice issues of the day. You can read them each day in our newsletter, The Daily Appeal. This week, the Supreme Court appeared ready to rule against convictions by nonunanimous juries. The Court heard arguments in Ramos v. Louisiana, a case that challenged the constitutionality of so-called “split verdicts.” For a long time, Louisiana and Oregon were the only two states that allowed juries in felony trials to reach a guilty verdict by a vote of 10-2 or 11-1. In 2018, Louisiana voters approved a constitutional amendment that eliminated nonunanimous verdicts going forward. But anyone charged with a crime that occurred before 2019 can still be convicted by a divided jury. And the amendment does nothing for those already serving time. Oregon’s law remains in place, having survived a recent attempt at reform. Both states’ rules are rooted in bigotry. The Louisiana law was part of a larger effort by white people to limit Black citizens’ participation on juries during Reconstruction. This effort included other Jim Crow rules, like a poll tax. Since almost every jury was predominantly white, the split jury rule ensured that the few Black jurors on any given jury would have little control over the outcome of a case. The law has worked as intended. Black jurors are disproportionately likely to be overruled by white jurors. Oregon’s law was borne of anti-Semitism, introduced after a jury came one vote short of convicting a Jewish man of murder. The acquittal gave way to rampant anti-Semitism and anti-immigrant discrimination, leading to the state constitutional amendment approving split verdicts. In federal courts, none of this is allowed. Supreme Court decisions dating back to the 19th century have found that the Sixth Amendment’s guarantee of a trial “by an impartial jury” in “all criminal prosecutions” means unanimity is required. But until the Civil War, the Sixth Amendment only applied to the federal government. When the 14th Amendment was ratified in 1868, most of the Bill of Rights, including the Sixth Amendment, was “incorporated” to the states. Last year, in Timbs v. Indiana, the Court found that the Eighth Amendment’s excessive fines clause was incorporated against the states, which means state governments are prohibited from imposing excessive payments as punishment for crimes. And the unanimous jury part of the Sixth Amendment was never fully incorporated. In 1972, in Apodaca v. Oregon, the Court ruled that the Sixth Amendment guarantees a right to a unanimous jury, “but that such a right does not extend to defendants in state trials,” according to SCOTUSblog. “The justices were deeply divided. Four justices would have ruled that the Sixth Amendment does not require a unanimous jury at all, while four others would have ruled that the Sixth Amendment establishes a right to a unanimous jury that applies in both state and federal courts. That left Justice Lewis Powell, who believed that the Sixth Amendment requires a unanimous jury for federal criminal trials, but not for state trials, as the controlling vote.” In 2016, Evangelisto Ramos was one of the people affected by this ruling. He was charged with second-degree murder, and, at trial, only 10 of the 12 jurors found that the prosecution had proved its case against Ramos beyond a reasonable doubt. Under Louisiana’s nonunanimous jury law, this was a guilty verdict, so Ramos was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole. At the Supreme Court, Ramos challenged that conviction, backed by various states, racial justice advocates, progressives, and libertarians. He argued that the Supreme Court should revisit Apodaca and ensure unanimous jury convictions for everyone, regardless of where they are charged. “Jeffrey Fisher, who argued for Ramos, plainly had a majority of justices in his corner from the start,” Mark Joseph Stern reported for Slate this week. “Only Justice Samuel Alito was vocally dismissive of his argument, complaining about stare decisis (or respect for precedent) … Why, he wondered, should the court knock down Apodaca when it has served the basis for thousands of convictions?” Fisher, Stern writes, had a good answer. “Apodaca rests on a single idiosyncratic concurrence, which rests on a theory of incorporation that the court has since discredited. This argument is so strong that Louisiana Solicitor General Elizabeth Murrill did not even contest it. Instead, she argued that nonunanimous verdicts should be allowed in both state and federal courts. Put differently, the court should overturn more than a century of precedent, dislodging the unanimity rule from the Sixth Amendment.” Justice Neil Gorsuch was apparently irritated by this idea. He asked what to do with the “14 cases throughout Supreme Court history that seem to treat unanimity as part of the Sixth Amendment?” Murrill then asserted that the state had “enormous reliance interests” on the preservation of nonunanimous juries because “32,000 people” might challenge their convictions if Apodaca is reversed. “It is unclear why Murrill thought all 32,000 people imprisoned in Louisiana could contest their verdicts,” Stern writes. “You say we should worry about the 32,000 people imprisoned,” Gorsuch responded. “One might wonder whether we should worry about their interests under the Sixth Amendment as well. And then I can’t help but wonder, well, should we forever ensconce an incorrect view of the United States Constitution for perpetuity, for all states and all people, denying them a right that we believe was originally given to them—because of 32,000 criminal convictions in Louisiana?” Even Justice Brett Kavanaugh, who seems to have a particular concern for racism in the jury process, seemed determined to rule for Ramos. He told Murrill that “the rule in question here is rooted in racism,” in a desire “to diminish the voices of black jurors in the late 1890s.” By the end of arguments, the question became not if the Court would rule for Ramos, but how broad that ruling would be. Would the rule affect those people whose cases are still on appeal only, or would it be fully retroactive, allowing thousands of people convicted by split juries to demand a retrial? The Daily Appeal spoke to Aliza Kaplan, law professor and director of the criminal justice reform clinic at Lewis and Clark Law School, who filed a brief in the Ramos case. She spoke about her surprise when she learned that Oregon’s attorney general filed a brief in support of Louisiana. Attorney General Ellen Rosenblum, Kaplan said, “has been doing a great job fighting against [President] Trump, and has come out publicly and said that she’s against non unanimous juries. She understands that they were conceived in discrimination.” But Rosenblum’s main concern, apparently, was about the threat of these cases “clogging up our court system.” Rosenblum warned that there could be “hundreds or thousands of nonunamimous convictions that would be contested if Ramos was successful.” Kaplan says that she asked for the list of those “hundreds of thousands of cases. I didn’t get one, but a reporter did get a list of 292 cases that the attorney general’s office said would be directly affected by Ramos. I went through 110 of those 292 cases, and I found that many of those cases did not fall in that category.” More important, Kaplan says, “arguments about the workload of government employees should be irrelevant when it comes to our constitutional rights. It’s not just the defendants’ rights at stake; it’s every juror’s rights, which is all of us. That is way more important than the state’s administrative convenience.” |