Political Report

Oregon Overhauls Its Youth Justice System

New law abolishes life without parole for minors, expands opportunities for early release, and restricts the prosecution of children as adults.

New law abolishes life without parole for minors, expands opportunities for early release, and restricts the prosecution of children as adults.

Oregon overhauled its youth justice system this week, advancing in one fell swoop goals that reformers have had for decades. Senate Bill 1008 squeaked by the legislature with the requisite supermajority in May, and was signed into law by Governor Kate Brown on Monday.

The bill abolishes life without parole for minors, expands opportunities for early release, and considerably restricts the prosecution of children as adults.

Reform advocates emphasized that plenty of work remains, especially insofar as SB 1008 is not retroactive. But they also told the Political Report that this as a major paradigm shift in the state.

“This is a historic moment for Oregon, and signifies a significant cultural and legal pivot in how we think about criminal justice and how we think about how we hold youth accountable for their actions,” said Bobbin Singh, executive director of the Oregon Justice Resource Center, a group that advocates for criminal justice reform. “We’re reversing nearly three decades of policy in our treatment of youth, all based on things we have come to understand as far as … the fact that youth have a unique capacity for rehabilitation and growth.”

Shaun McCrea, executive director of the Oregon Criminal Defense Lawyers Association, agreed that “this is just a fantastic opportunity for Oregon because there’s finally a recognition that juveniles aren’t simply small adults, and they need to be treated differently.”

SB 1008 scales back Measure 11, a ballot initiative that Oregon voters approved in 1994. Among other provisions, Measure 11 required that anyone over the age of 15 be tried as an adult if charged with a qualifying offense; those offenses carried minimum sentences with no prospect of a reduced sentence. To amend Measure 11, both legislative chambers needed a two-thirds majority; SB 1008 reached that threshold with no votes to spare in the Senate. The reform was mainly carried by Democrats, but GOP support proved decisive; GOP Senator Jackie Winters, who strongly championed the reform, died a week after it was passed by the legislature.

The Oregon District Attorneys Association lobbied against the legislation. Singh characterized their intervention as “a lot of fear and anger politics,” adding this was consistent across reforms discussed this year.

The Political Report reviews the main provisions of SB 1008, and how they shift the national landscape on youth justice, below.

A new milestone in efforts to curb excessive sentences

SB 1008 bans sentences of life in prison without the possibility of parole for offenses committed before the age of 18.

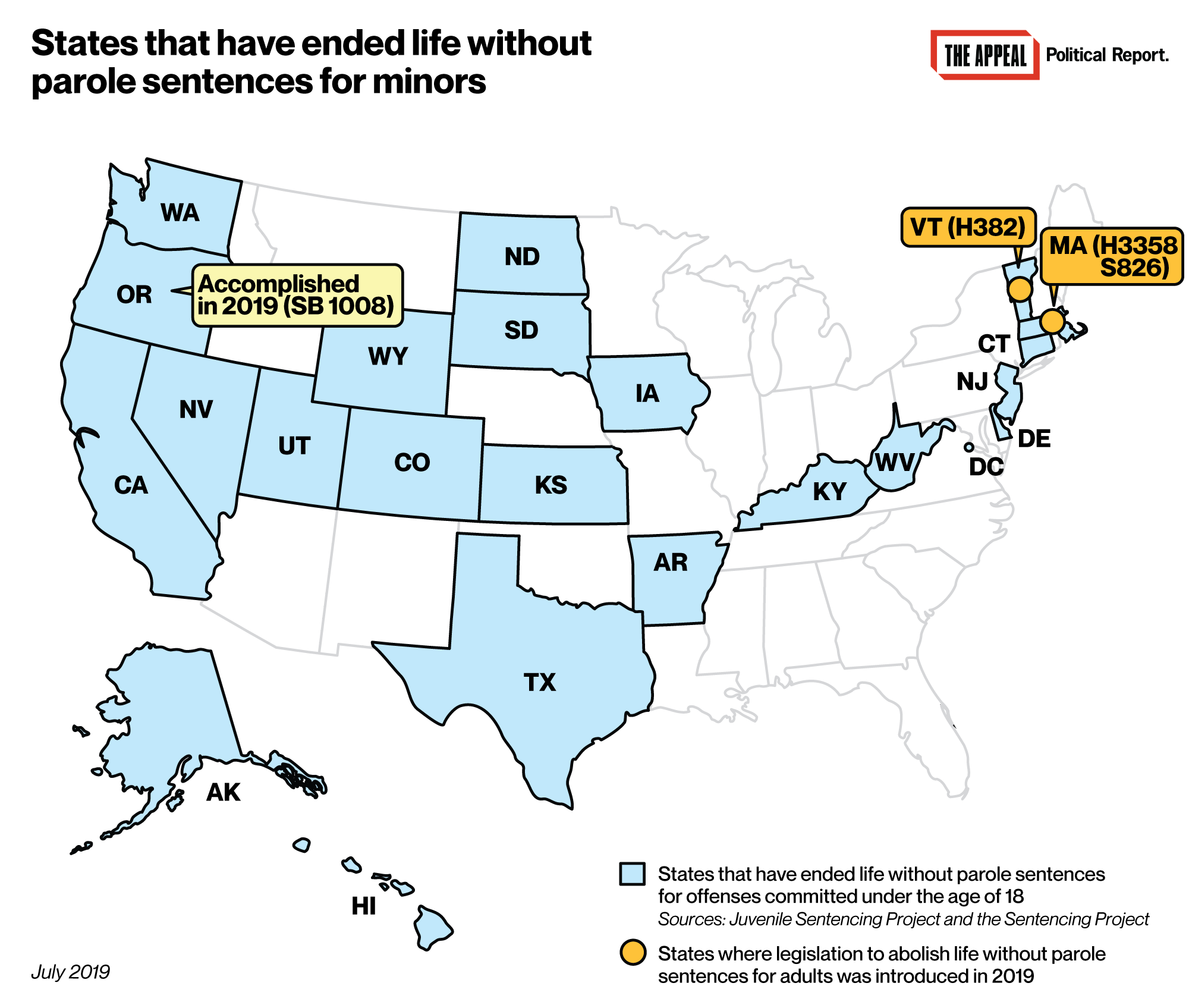

There are now 22 states plus D.C. that have ruled out this sentence. Nineteen have done so since 2012, according to a tracker maintained by the Juvenile Sentencing Project. Some states are now discussing abolishing it for adults too.

But SB 1008 also targets de facto life sentences and other lengthy sentences, ones that are not technically life without parole but leave people with no chance for release for decades.

It offers people convicted of offenses committed when they were under 18 a chance for early release or for a revised sentence (what the bill calls a “second look”). Depending on the circumstances, they will be eligible for parole or for a judicial review after 15 years of imprisonment, after serving half of their sentence, or upon turning 25.

These mechanisms change the eligibility for release, but they do not outright block excessively long prison sentences. How they are implemented is crucial. “This will be the challenge,” Singh said, “how to ensure that we are educating judges who oversee second chance hearings, and how do we work with the parole board to make sure that the criteria that they’re using is consistent with current practices and science.”

McCrea described herself as “cautiously optimistic” when asked if the conditions exist for incarcerated people to have a fair shot in these hearings. “The very dedicated lawyers in Oregon will use this as an opportunity to fight even harder,” she said.

New limits on prosecuting minors in adult court

Under Measure 11, people over 15 were necessarily treated as adults when prosecutors charged them with some offenses, with no opportunity to review or challenge this jurisdiction. “Oregon’s Measure 11 dumped thousands of children into the adult system automatically,” Marcy Mistrett, who heads the Campaign for Youth Justice, a group that works on this issue nationwide, told the Political Report in an email. And it’s a “BIG DEAL” that this will now change, she wrote.

Oregon will no longer require that some offenses always be prosecuted in adult court, regardless of the defendant’s age.

The new law still allows for adult prosecution in some circumstances, but this will no longer be automatic or mandatory. In addition, SB 1008 does not trust prosecutors with making the decision on their own. They must request approval from a judge in a waiver hearing.

“Now we will have a criminal system that starts with the assumption that youth are youth,” Singh said.

But Singh also warned it will take continued work to fight the transfer of minors into adult courts. “It’s going to be challenging to make sure that these waiver hearings are done correctly,” he said, noting that this will vary based on local circumstances and officials. “If they’re done correctly, what we will see is very few if any youth transferred into the adult system.”

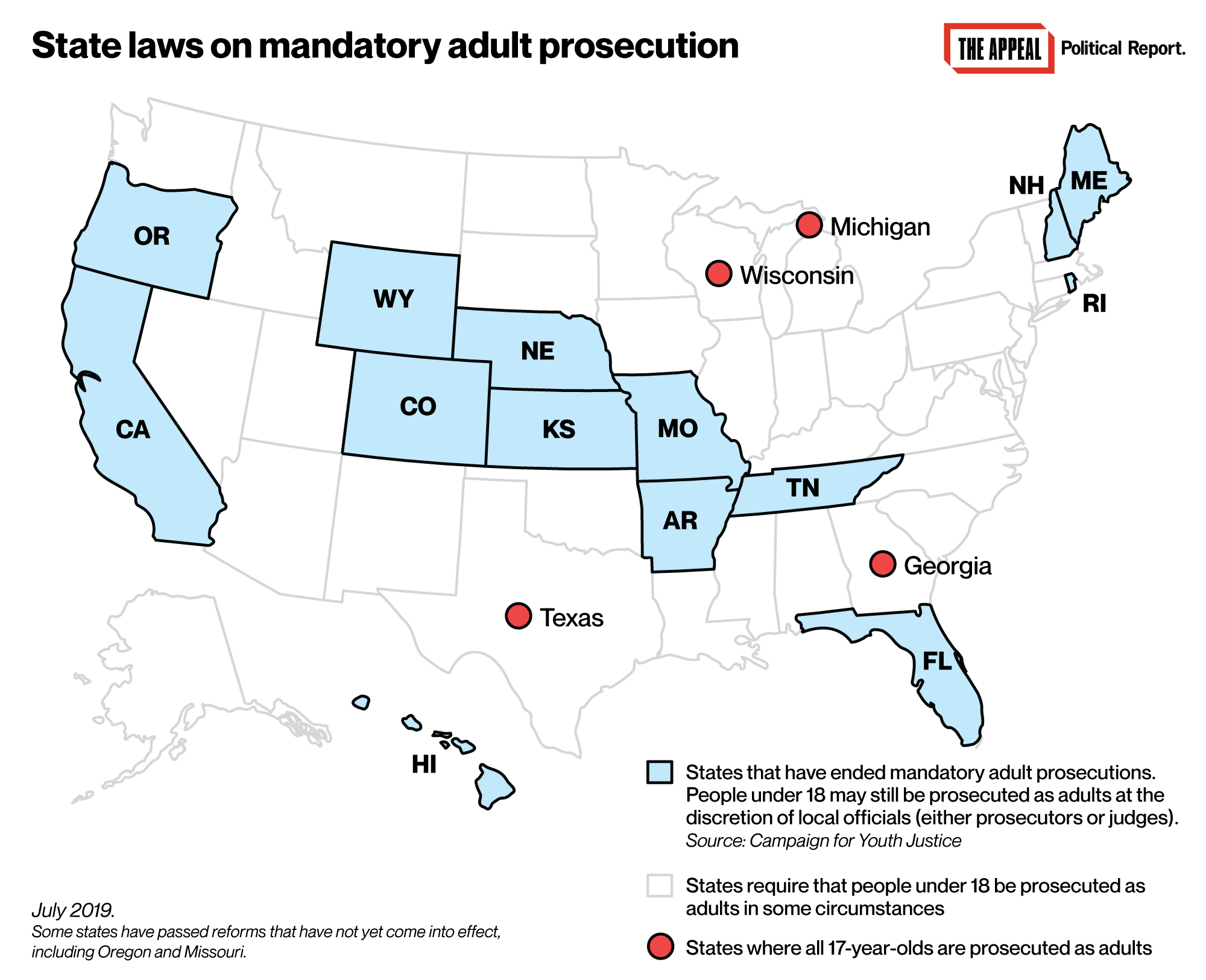

Oregon is part of a wave of states that are changing the rules under which minors are moved to adult court. Florida and Rhode Island ended mandatory adult prosecutions over the last year, Misrett noted. Some states have also ensured that judges and not just prosecutors have a say.

“We have learned a lot in the past 15 years about what works with young people who come in contact with the justice system, even those who commit serious crimes or crimes that involve violence,” Misrett said, referring to studies on the harmful repercussions of adult prosecutions and to the findings “that most young people ‘age out’ of criminal behavior.”

Oregon’s reform still leaves 36 states where minors are automatically treated as adults in certain circumstances. That’s usually because of requirements like the ones Oregon just overturned. But four states have still not raised the age of criminal jurisdiction to 18, even as elsewhere in the country advocates are pushing to raise the age to 21. In those four states, all 17 year-olds are prosecuted as adults.

What about people who are already convicted?

SB 1008 is not retroactive. People with existing convictions will receive no second chance even if their sentence would be considerably different under the new rules. This lack of retroactivity is common but not universal in sentencing reforms, and it creates huge disjunctions in how harshly people are treated for a similar offense.

McCrea hopes that the new sentencing regime will get lawmakers to revisit why they are denying its rehabilitative principles to people currently serving sentences. It “will shine a spotlight on cases where juveniles have already been convicted, and maybe allow the system to do a second look down the line,” she said. “But it’s going to be a very cautious and slow process.”

Singh agrees. He called it “a priority… to figure out, either through the courts or the legislature, how to push forward with retroactivity.” With this, just as with monitoring implementation of the “second look” and waiver hearings, he emphasized that the work is only just beginning.

“We’re trying to reverse 25 years of culture here in Oregon in how we think about youth, and that’s not going to be easy,” he said. “There’s a lot of system stakeholders and agencies that have to reorient their thinking, and that’s going to take a lot of effort.”