Political Report

Advocates Press States to Recognize that Young Adults Can Change Too

Illinois law uses a cutoff age of 21. Advocates ask, why should people be cut off from the logic of having a separate youth justice system because they are a day over 18?

New Illinois law institutes a parole process, and applies this up to age 21. Other states have adopted or are considering similar reforms.

Why should people be cut off from the logic of having a separate youth justice system—that people change, that people grow, that people should not be defined by an act—because they are a day over 18?

A new Illinois reform (House Bill 531), signed into law this month by Governor J.B. Pritzker, defies the usual pattern that in the United States even bold youth justice reforms stop at the age of majority, if not earlier.

It does so by creating a parole process for most people who will be convicted of offenses they committed before the age of 21, providing them review after either 10 years or 20 years depending on the offense category. Jobi Cates, executive director of Restore Justice, an Illinois-based group that helped craft and steer HB 531, told me that the law starts “chipping away at what’s been a completely merciless system.”

While the law has major limitations, it also opens doors to think differently about what criminal justice reform can look like.

It builds on two reform areas that are bubbling up nationwide—first in challenging the upper limit of youth justice, and second in promoting a mechanism with which to counter virtual life sentences.

Reintroducing a parole process

Illinois eliminated its parole process in 1978. Last year, an Injustice Watch investigation found that 167 people who were incarcerated in Illinois for crimes they committed as minors were scheduled to spend at least 50 years in prison without parole eligibility.

HB 531 seeks to counter sentences like these in the future. It reintroduces in Illinois the idea that one should at least have the ability to petition for parole, and it enables such petitions within the first two decades of incarceration rather than centuries in the future.

According to the Chicago Tribune, this is the first Illinois measure to allow some new group of people to petition for discretionary parole since 1978. (Illinois has kept a parole process just for people convicted prior to 1978.) Cates said that the law is the product of “years of attempts at various kinds of legislation that would introduce meaningful opportunities for release for people in Illinois who are trapped in a system that doesn’t offer parole.”

It will not help those 167 prisoners, however, since it is not retroactive. Cates urged lawmakers to revisit this. “We are getting letters from people who won’t be getting released but who are desperate to show that they’ve changed, and there’s no mechanism to show that they’ve changed,” she said. (The Illinois Supreme Court issued a separate decision that could provide some of these people a shot at release.) The law has other restrictions that will limit its impact. It provides individuals a finite number of reviews over the course of their sentences. Also, people convicted of certain offenses and people who receive a natural life sentence have been carved-out from the legislation.

Still, future Illinois reforms can jump off of this new law rather than argue for instituting the very notion of parole. “You could continue raising the age, you could incrementally increase the number of reviews, you could increase the quality of review or the standards of how reviews are conducted,” Cates said. “There are dozens of ways you could make this better.”

In taking a first restricted step against life and virtual life sentences and by applying it to young adults, Illinois’s new law emulates a series of reforms recently adopted in California. In 2014, California adopted a system for people who committed crimes as minors to eventually be granted a “youth offender parole hearing.” (The hearing would come 15 to 25 years after incarceration.) Subsequent bills raised the age of eligibility for this “youthful” hearing, first to people under 23 and then to people under 26.

Lawmakers elsewhere have proposed similar if not bolder legislation. In at least two states, legislation introduced this year would make all incarcerated individuals (regardless of age) eligible for parole after 25 years of incarceration. Elsewhere, legislative proposals create opportunities for release, or move them forward in time, but use a cutoff age of 18.

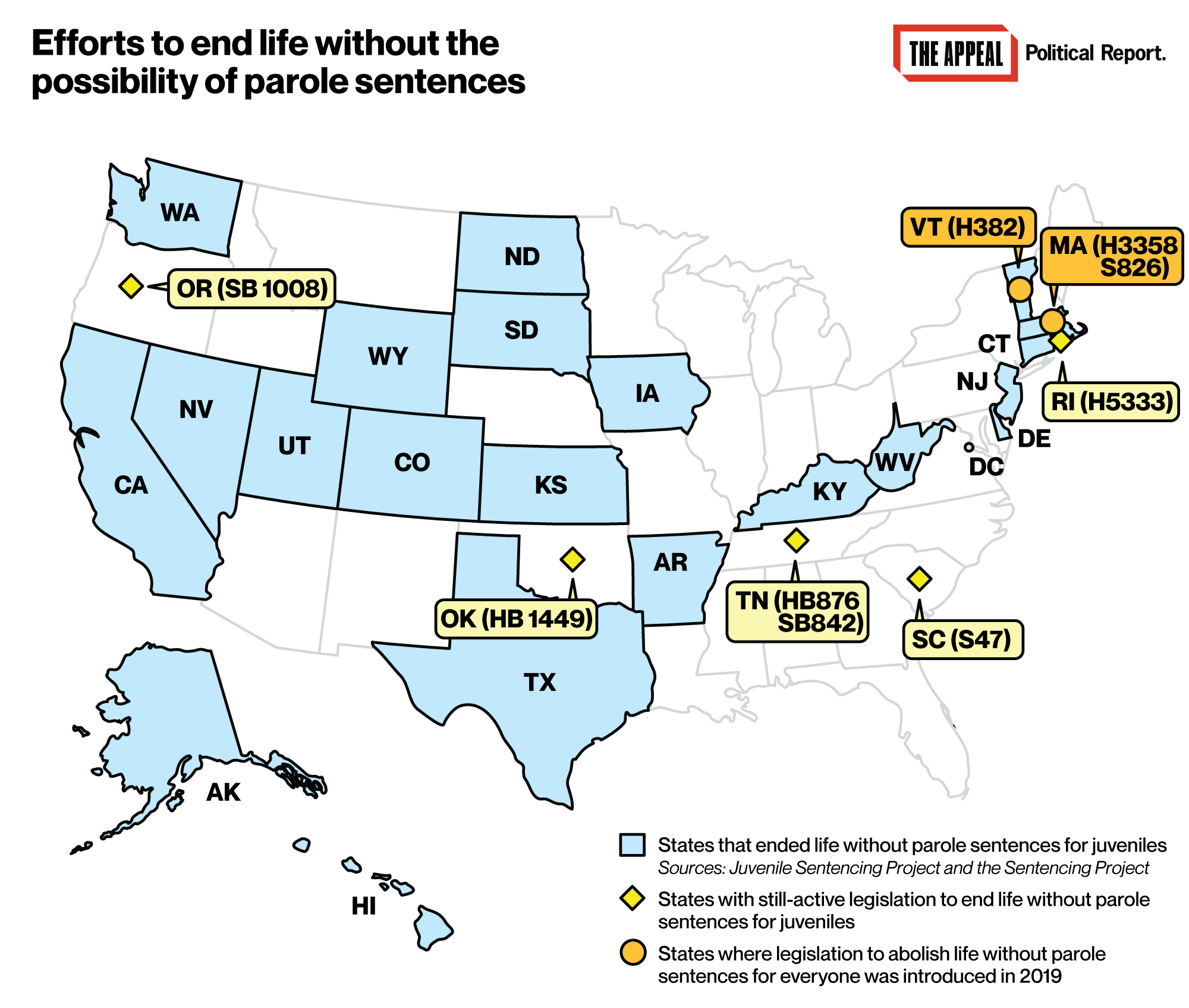

In Rhode Island, for instance, a pending bill would mandate that a person be eligible for parole after 15 years if convicted as a minor. Its sponsor, state Representative Marcia Ranglin-Vassell, wrote in an email that she believed in “the restorative power of love to change and make us better human beings in spite of our past.” In 2017, the Senate passed similar legislation, which did not pass the House. A bill has stalled in the House Judiciary Committee again this year. Ranglin-Vassell expressed optimism that the bill could still pass. Oklahoma, Oregon, South Carolina, and Tennessee also have active bills that would end life-without-parole sentences for juveniles.

Raising the age to 21, or at least 18

The Illinois law also challenges the idea that youth justice stops at 18.

This upper line is ingrained in many criminal legal rules, but efforts are multiplying nationwide to question why it should be so strict. Beth Schwartzapfel reported on these efforts, and some of their early successes, in the Marshall Project last year.

“A line must be drawn,” Justice Antony Kennedy wrote in a 2005 decision, which also recognized that “the qualities that distinguish juveniles from adults do not disappear when an individual turns 18,” and also that “some under 18 have already attained a level of maturity some adults will never reach.” But Kennedy made this statement in a decision that itself moved the line at which one could be sentenced to the death penalty from 16 to 18.

Now, some advocates are asking for the line to be moved further.

Last year, Vermont became the first state to raise the age of juvenile jurisdiction above 18. It now steers some 18- and 19-year-olds to its juvenile justice system. Juvenile courts typically provide defendants more opportunities for alternatives to prosecution and incarceration, less harsh outcomes, and protections like confidential records.

HB 531 does not do this. It makes some young adults convicted in the adult system eligible for parole. According to Cates, this alone is the first criminal justice law in Illinois to use the age of 21. “21 is a more reasonable benchmark of maturity than 18 for the purposes of this type of punishment, particularly given how severe the punishments are,” she said.

But Illinois is now considering separate legislation to emulate Vermont and raise the age until which people charged with misdemeanors are treated as juveniles from 18 to 21. Vincent Schiraldi, who heads Columbia University’s Justice Lab, thinks that this proposal is a natural offshoot of HB 531, the new law on parole. “Whatever logic plays into you treating them specially at parole, whether it’s developmental or sociological or just your gut thinking, that has to impact your thinking about them having committed misdemeanor offenses at the front-end,” he said.

Turning 18 should not block access to more rehabilitative approaches, Schiraldi added. “Think about what the makeup of this 18-, 19-, 20-year-old population and where we would like to have them,” he said. “The adult system is a meat grinder. The juvenile system is far from perfect, but at least it gives confidentiality protection, and it takes a shot at rehabilitation. No one is pretending rehabilitation occurs in the adult situation. I’m not saying it shouldn’t, but until it does the juvenile system is where young adults should be.”

Columbia University’s Justice Lab released a report co-authored by Schiraldi in January on how young adults are treated in Illinois. It finds that racial disparities in incarceration are greatest for people between 18 and 25. The report also questions existing practices by drawing on the research in neurobiology and psychology that finds that people’s brains “continue to develop into a person’s mid-20s, and even beyond.” Elizabeth Clarke, the executive director of the Illinois-based Juvenile Justice Initiative, makes a similar case. “Older adolescents need the same protections that we extend to youth under the age of 18,” she wrote in an email. She pointed to the difference in how young adults are treated in the U.S. and in Germany, whose youth justice system is far more expansive.

Connecticut and Massachusetts advocates have also championed allowing some defendants up to age 21 to qualify for juvenile court, though these efforts have not been successful so far.

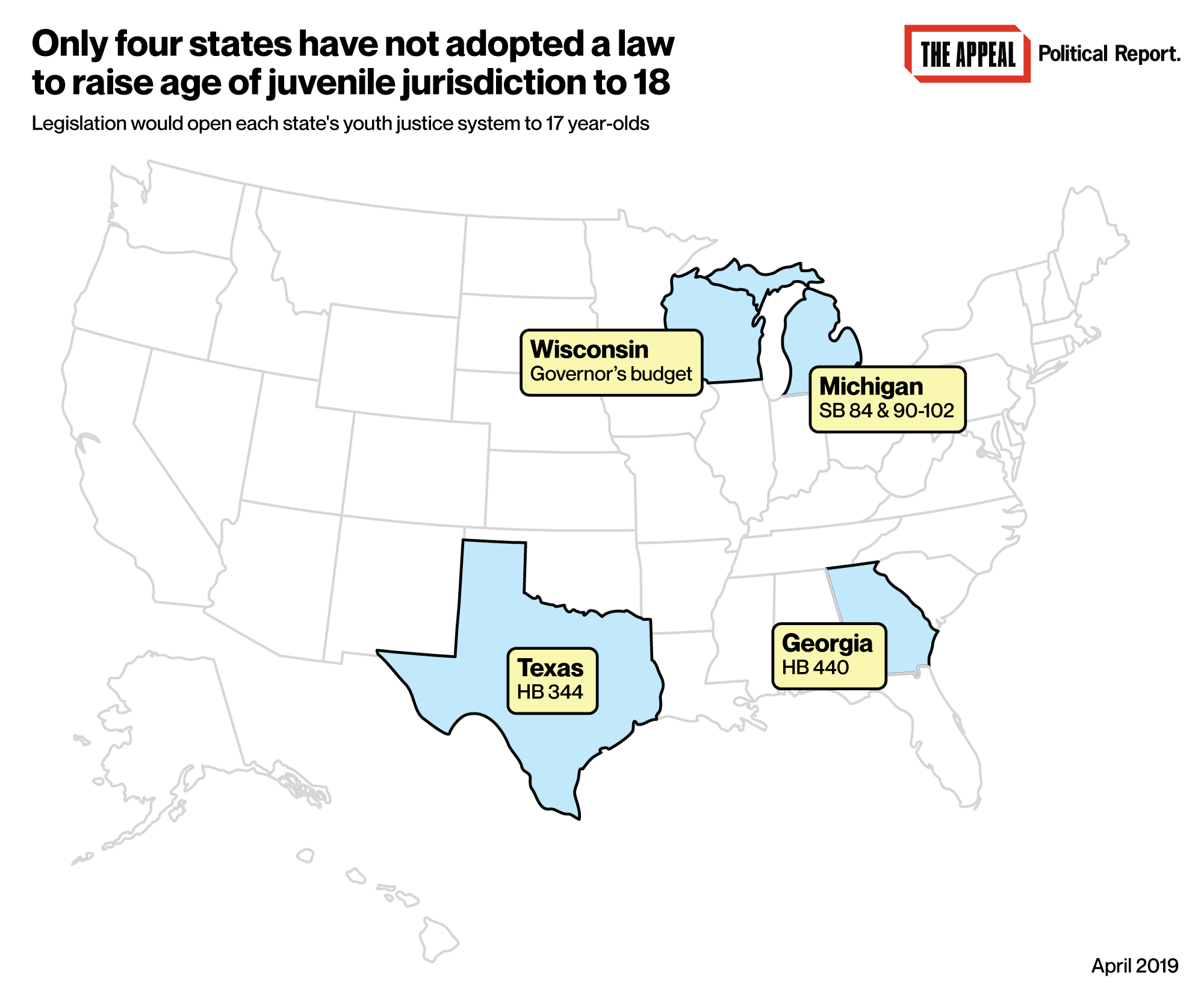

Meanwhile, a handful of states are still debating getting to 18.

There are four states—Georgia, Michigan, Texas, and Wisconsin—where the juvenile system stops at 17 for everyone, and where there is no scheduled change on the horizon. (Some other states like Missouri and New York have raised this age to 18 but have yet to fully implement the reform.) This means that in those four states 17-year olds are automatically treated as adults.

Raising the age to 18 has been a priority for criminal justice reform advocates in these states. On Wednesday, the Michigan Senate adopted a package of bills that would raise the age to 18. This package, which would automatically treat 17-year olds as juveniles, is now up to the state House, where it has already advanced past the committee stage.

In the three other states, similar legislation has yet to move as far. A bill moved out of one Texas committee in March. Another is still in committee in Georgia. In Wisconsin, Governor Tony Evers included “Raise the Age” in his first proposed budget.

Such bills do not guarantee that minors will remain in the juvenile justice system. They only extend that system, so that 17-year-olds are not excluded from it just by virtue of their age. That’s because, besides the age of juvenile jurisdiction, there is a separate question as to the circumstances under which juvenile defendants get treated as adults. Even 11- or 12-year-old children, if not younger ones, can be tried as adults, and separate reform proposals abound whose aim is to narrow, if not eliminate, these circumstances.

“A nose under the tent”

But if you want rehabilitation to be a goal of the criminal legal system, should programs and release opportunities meant to promote it ever be restricted by age?

I asked Schiraldi if he worried that improving the treatment of only young adults risked leaving others behind. He expressed hope that “provisions will come into effect for this age group, and then they’ll start to catch on, and people will say, ‘Well, if it works for them, maybe it’ll work for older people.’” He added, “If all of a sudden this population that has never had access to these kinds of rehabilitative programming, and confidentiality, and charge expungement, which is routine in the juvenile system, all of a sudden three years of quote on quote adults get it, and do well with it, how do you not say that some of those things should apply to older people?”

The gradual expansion of California’s “youth offender” status since 2014 illustrates this pattern.

Similarly, bills proposed in Pennsylvania last year and in Massachusetts and Vermont this year to abolish life without parole sentences would build on these states’ prior abolition of juvenile life without parole sentences.

“The young adult conversation might be the nose under the tent for the humanization of our prisons,” Schiralrdi said. “That’s my hope, anyway.”