Political Report

Hawaii Proposal to End Disenfranchisement Stalls as Advocates Vow to Press Ahead

“People don’t lose their citizenship just because they’re sentenced to prison,” said one advocate.

“People don’t lose their citizenship just because they’re sentenced to prison,” said one advocate.

This article is part of a state-based series on disenfranchisement.

A legislative committee in Hawaii’s Senate voted in February to advance a bill abolishing felony disenfranchisement, a significant move since Maine, Puerto Rico, and Vermont are the only places in the United States that do not disenfranchise people because of a felony conviction.

But the deadline for the legislation to make it out of committees has now expired with no action from the other committees to which it was referred. This means that Senate Bill 1503 is effectively tabled for the year. The bill will carry over to 2020, and proponents told the Political Report that they would press ahead then.

Hawaii currently strips people of the right to vote while they are incarcerated for a felony conviction, and restores it upon their release from prison. SB 1503 would reform that practice by enabling incarcerated people to cast absentee ballots. State advocates describe this step as crucial to achieving a healthier democracy. “If we want people to be full human beings and full citizens, we need to make sure that everybody has the right to vote,” Kat Brady, the coordinator of the state group Community Alliance on Prisons, told me. “What happens in the voting booth affects their families. The families are sending the money for phone calls, for commissary stuff, so it’s ridiculous to think that there’s no nexus between voting and citizenship and incarceration.”

Janet Mason, the chairperson of the legislative committee of the League of Women Voters of Hawaii, which has also championed this legislation, agrees that the right to vote is not something to take away. “People don’t lose their citizenship just because they’re sentenced to prison,” she said.

Brady and Mason both also argued that maintaining voting rights can facilitate eventual re-entry by connecting individuals to their communities. “If we want people to enter the community as full citizens, then what better way than to help them engage” while they are in prison, Brady said. The isolation of incarcerated Hawaiians is exacerbated by the fact that a substantial share are in out-of-state facilities; 1,450 are detained in a private prison in Arizona.

The state’s carceral system disproportionately ensnares Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders, who are therefore also disproportionately excluded from the electoral process.

According to a 2010 report by the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, Native Hawaiians make up 39 percent of the incarcerated population but only 24 percent of the general population and 27 percent of those arrested. The study found specifically that “for any given determination of guilt, Native Hawaiians are much more likely to get a prison sentence than almost all other groups, except for Native Americans,” and this even “controlling for age, gender, and type of charge.”

That measure is directly relevant to voting rights since Hawaii uses incarceration—as opposed to other forms of sentence like probation—as the specific basis on which to disenfranchise people who are convicted of a felony.

State Senator Maile Shimabukuro pointed to the overrepresentation of native Hawaiians in the state’s prisons to explain why she was sponsoring this reform. “It promotes engagement for disenfranchised segments of our society,” she told me via email. “This bill is a step toward re-integrating native Hawaiians and other minorities back into our political process, and showing them that their voices matter.”

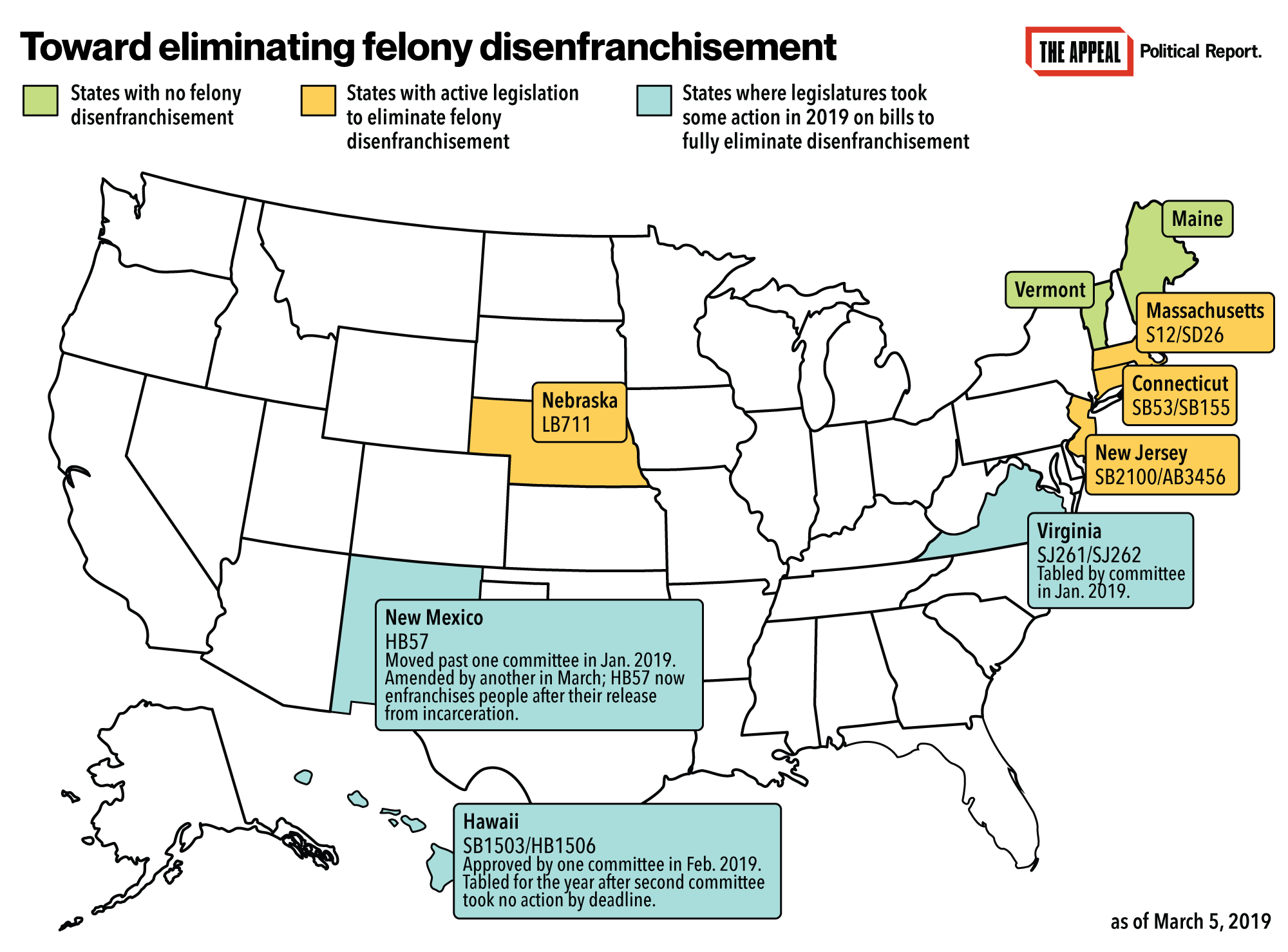

Besides Hawaii, bills that fully abolish felony disenfranchisement have been introduced in at least six other states in the present legislative sessions.

Hawaii is one of two states, the other being New Mexico, where a full abolition bill moved past a legislative committee this year. Neither state is still considering such a step in their current session.

The director of Hawaii’s Department of Public Safety, which is responsible for the state’s prison system, came out in support of the legislation in a testimony in the Senate Committee on Public Safety, Intergovernmental, and Military Affairs. On Feb. 5, that committee unanimously voted to advance the legislation to the joint Judiciary and Ways and Means committees, where the bill stalled. “I was disappointed that the Judiciary decided not to hear it,” Brady said.

Senator Karl Rhoads, the Democratic chairperson of the Judiciary Committee, did not reply to a request for comment on his views on the legislation or on his reasons for not scheduling a hearing.

Mason told me that one obstacle may have been a belief among lawmakers that they need to first shore up the state’s voter registration procedures and absentee voter program. The legislature is still considering adopting automatic registration bills and reforms to its vote-by-mail system. “Those two things would greatly enhance the chances of getting the voting rights for incarcerated folks well positioned to pass,” she said.

Brady thinks that SB 1503 did not generate sufficient interest, and was mainly derailed by lawmakers’ indifference toward the issue. But she also said the bill’s future success hinged on a broader shift to the way in which state politicians’ approach criminal justice issues. “Hawaii can’t seem to get off the punishment train,” she said. “The legislature is very fearful to give any sort of rights to people who have violated the law. … We are so afraid of people who have drug problems or mental health problems—‘they’re in prison so they’re bad and we don’t want them weighing in on anything’—and I’m like, ‘Get a grip, guys.’”

Brady added, “To me it’s about racism, it’s about slicing and dicing the society to say they are good people and there are bad people and we have determined whose bad and we are going to keep punishing them.”