Political Report

California's New Reforms Went into Effect, but Implementation Challenges Lie Ahead

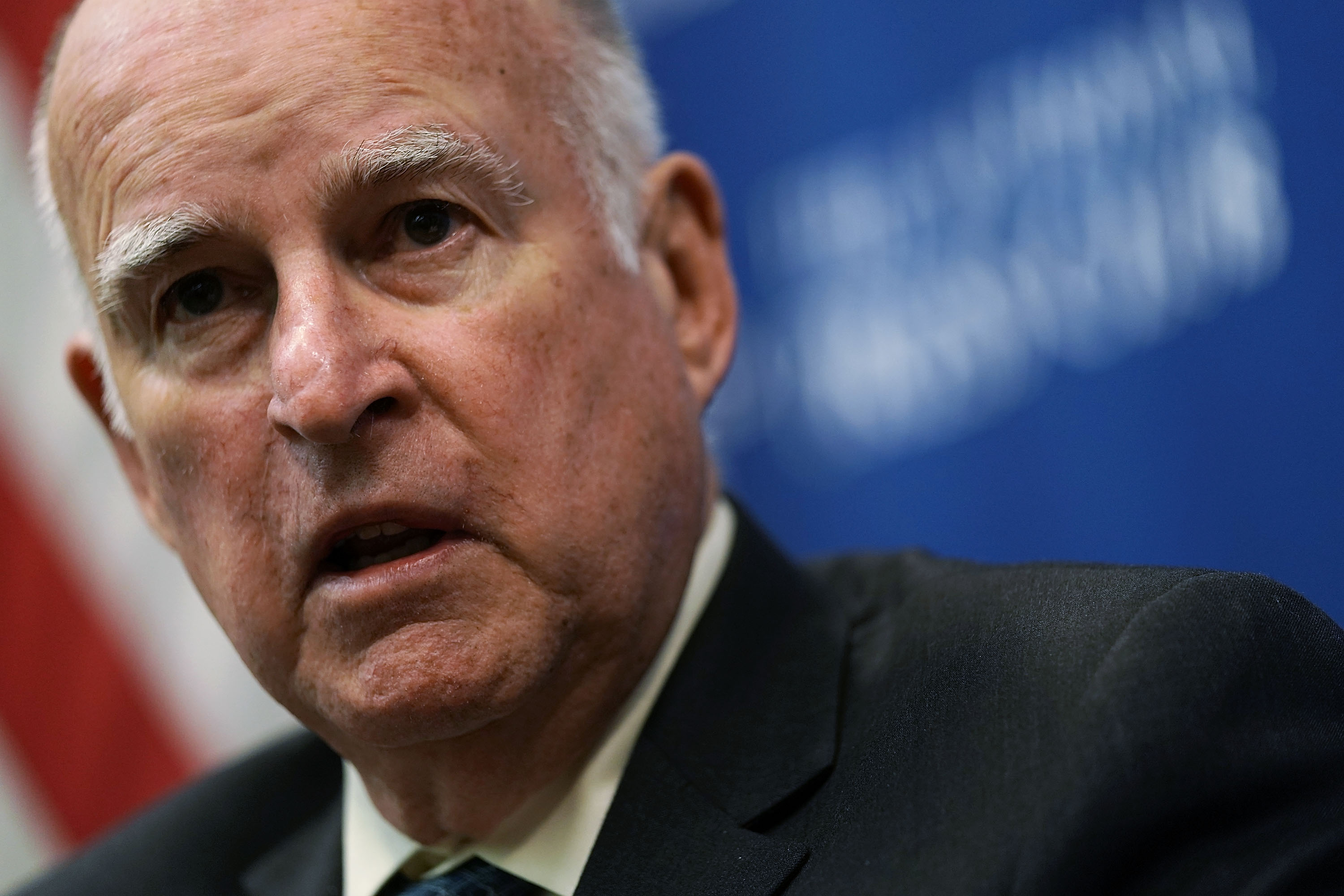

Police transparency, marijuana expungement, and more: Jerry Brown signed a series of reforms that just went into effect, but their implementation hinge in part on local officials.

Daniel Nichanian

In September, California Governor Jerry Brown signed a series of reforms that just went into effect at the beginning of 2019 and will transform the state’s criminal justice system. But their scope and the ease with which they will be implemented hinge in part on local officials.

Improving police transparency: Two laws that affect policing came into effect on Jan. 1: They require the public release of body camera footage (Assembly Bill 748) and the public release of records pertaining to officer shootings and misconduct investigations (Senate Bill 1421). Until their adoption, “California was the only state that had a complete lock on any public access” to disciplinary records, state Senator Nancy Skinner told the Appeal: Political Report in October.

But one early test of their impact already met a roadblock. On Jan. 1, the East Bay Express filed a Public Records Act request to obtain records pertaining to the death of Elena Mondragon, an unarmed teenager who was shot and killed in 2017 by two Fremont police officers. The city of Fremont responded to this request with a blanket denial within two weeks, citing a lawsuit filed by Mondragon’s family as the grounds for refusal.

Melissa Nold, an attorney who has represented the Mondragon family, believes that these new laws will require legal wrangling if they are to have a solid impact. “The [police] departments that want to be transparent will use this as an opportunity, but a lot of the departments already didn’t release information that they were supposed to,” she told me. She expects uncooperative departments to continue finding reasons to refuse the release of records. “There is really no repercussion for them, because you can take them to court and all they might have to do is release the information,” she said. “This is one of those things that will have to be tested in court to see what they are or aren’t allowed to conceal.” The Guardian’s Sam Levin reported in 2018 that the opaqueness surrounding Mondragon’s death has contributed to its relative social media invisibility and to a lack of consequences for the officers involved.

Reforming the felony murder rule: Senate Bill 1437, the law that restricts the circumstances under which someone can be prosecuted for a murder that they did not commit, went into effect on Jan. 1. Because the law is retroactive, people with an existing murder conviction can petition for a new sentence if they would not have been convicted under the new law. But the office of San Diego District Attorney Summer Stephan is preparing to challenge its constitutionality as soon as someone files a resentencing petition, according to Inewsource. Most California DAs had urged Governor Brown to veto this legislation before it became law.

Facilitating expungement of marijuana convictions: Few Californians petitioned to have their marijuana-related convictions expunged or reduced after the state eased that process in 2016. Assembly Bill 1793, which just took effect as well, takes a new approach to clearing criminal records. It requires that state officials identify all individuals eligible for relief by July 1, 2019. “It’s very expensive, time-consuming to navigate the process on one’s own,” Rodney Holcombe, a staff attorney with the Drug Policy Alliance, told me. “Folks are no longer burdened with having to initiate this cumbersome process. Instead the state has to initiate.”

The state’s Department of Justice will then provide county DAs with their information. Each DA must process these files and decide whether to challenge expungement on a case-by-case basis. Individuals whose cases are not challenged by a DA will have their records modified by July 1, 2020; when DAs challenge someone’s file, they must make an effort to notify the convicted individual and a public defender’s office to give them opportunities to respond.

This means that slow or uncooperative prosecutors could hinder the law’s implementation, and create geographic disparities in the ease with which individuals clear their records. Holcombe, however, noted that he had not heard opposition from individual DAs, and that California’s DA association had not opposed AB 1793. “To date we haven’t heard any pushback from DAs,” he said.

Holcombe added that another possible hindrance was disparities in resources. “We have counties like San Francisco that are better resourced, with more streamlined processes to move through the files,” he said. “How else can we make sure that counties are well-resourced enough to do it?”