Political Report

Sparse Competition in 2018 Prosecutorial Elections

An analysis of California, Minnesota, Oklahoma, and Utah in the 2018 midterms

An analysis of California, Minnesota, Oklahoma, and Utah

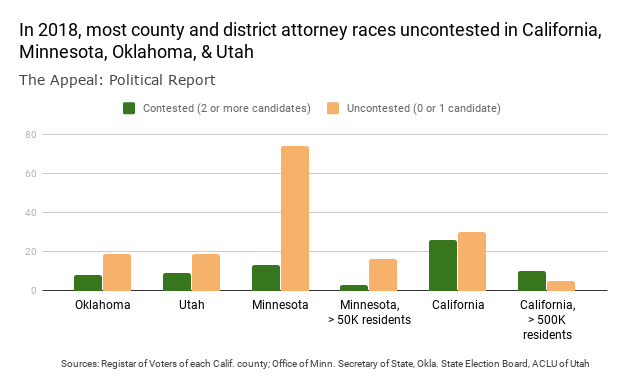

Promoting prosecutorial accountability and criminal justice reform in the electoral arena depends on vigorous competition, but that’s far from the norm. One candidate stands unopposed in most prosecutorial elections, as studies like this 2009 article by Robert Wright have found. That’s holding true in 2018, as I found when I examined county-level district attorney contests in four states. Take a look at Utah and Oklahoma, which held their primaries on June 26; Minnesota, where early voting began on June 29; and California, which held its primary on June 5.

Oklahoma is hosting 27 races for district attorney this year, but 19 of them drew just one candidate. Similarly, Utah is hosting 28 races for county attorney, 19 of which feature no competition on the ballot. Besides the 16 Utah incumbents who are unopposed in both the primary and the general election (one did face challengers at the county convention), there are three small counties with no candidate at all. Only six of Utah’s 28 races featured competition in the June 26 primary; only five will feature multiple candidates on November’s ballot.

The landscape is even more uncompetitive in Minnesota, which is electing 87 county attorneys this year: 74 of these races (85 percent) feature only one candidate.

The share of contested races remains very low in Minnesota’s most populous counties: Just three of the 19 counties with more than 50,000 residents (Hennepin, Ramsey, and Olmsted) feature more than one candidate. Even then, only one of Ramsey County’s two contenders is running an active enough campaign to have a website at the moment. In Hennepin and Olmsted, longtime incumbents Michael Freeman and Mark Ostrem face challenges on the November ballot, but neither has faced a challenger since 2006; both ran for re-election unopposed in 2010 and 2014.

California posts a higher rate of contested DA elections. But here, too, a majority of this year’s elections—30 of 56, about the same ratio as four years ago—feature only one candidate.

The pattern looks different in California’s largest counties: 10 of the 15 elections in counties with more than 500,000 residents drew multiple candidates. Most of these ended in June’s all-party primary because a candidate got a majority of the vote; only two elections remain contested in November, where turnout will be considerably higher. This is unfortunate in that most of California’s contested district attorney elections are decided by a smaller electorate than could be the case. (In 2014, participation in the primary was 59 percent of November’s.) California could look toward Minnesota for a way to alleviate this: Minnesota waits until November to hold a vote for county attorney if only two people have filed, rather than resolve it in a lower-turnout summer election.