Political Report

Voters Restrict ICE’s Reach in Key Counties around the Nation

“People showed up yesterday because they want their local communities to revolve [around] their values,” said a Maryland advocate.

Daniel Nichanian

Voters on Tuesday put ICE on notice in several states and counties. “People showed up yesterday because they want their local communities to revolve [around] their values, even if what happens in Washington does not for the foreseeable future,” Elizabeth Alex, senior director of community organizing at CASA, told The Appeal about elections she was tracking in Maryland.

Before Election Day, I previewed the campaign’s stakes for immigration policy in key counties. One important question was the fate of candidates who pledged to terminate their counties’ participation in ICE’s 287(g) agreement, which deputizes local officers to act like federal immigration agents and investigate people’s immigration statuses.

At least three such candidates won offices that will enable them to withdraw from an existing 287(g) deal. They are: Garry McFadden, who will be sheriff of Mecklenburg County, North Carolina (Charlotte); Gerald Baker, who will be sheriff of Wake County (Raleigh); and Steuart Pittman, who will be county executive of Anne Arundel County, Maryland (Annapolis). In addition, Democratic Sheriff Doug Mullendore of Washington County, Maryland, won against a a challenger who campaigned on having the county join 287(g). However, in two other Maryland counties already in it (Harford County and Frederick County), incumbents beat challengers.

Baker’s win came over Wake County’s longtime sheriff Donnie Harrison, who joined the 287(g) program in 2007 and who has consistently defended practices that immigrant advocates worry will lead to increased deportations.

The sheriff of Hennepin County, Minnesota, appears to have lost his re-election bid as well, again in an election in which his cooperation with ICE loomed large. While Hennepin County is not party to the 287(g) deal, Rich Stanek’s policies of sharing information about the people he detains, and of giving ICE access to these detainees, have drawn protests, as I wrote in July. Stanek’s loss to Dave Hutchinson was an upset that will be felt beyond Minneapolis since Stanek is an influential figure who was scheduled to soon preside over the National Sheriff’s Association. In New York, another sheriff known for aggressive law enforcement practices, Paul Van Blarcum of Ulster County, lost to Juan Figueroa, who denounced the incumbent’s “hard-line policy of reporting immigrants under custody to ICE.” In Oregon, voters upheld their sanctuary law, which restricts cooperation over immigration between local forces and the federal agency, in a referendum.

However, in Orange County, California, Undersheriff Don Barnes was elected sheriff. Barnes has defended the department policy of circumventing California’s new sanctuary law and still getting ICE the information it might want. Barnes has said that cooperating with ICE is essential to targeting “high-level criminals,” a claim that considerably misstates the range of people about which his department has been notifying ICE. “They paintbrush the immigrant community as criminals as a whole,” Roberto Herrera, the community engagement coordinator at Resilience Orange County, told me in October about the sheriff’s office.

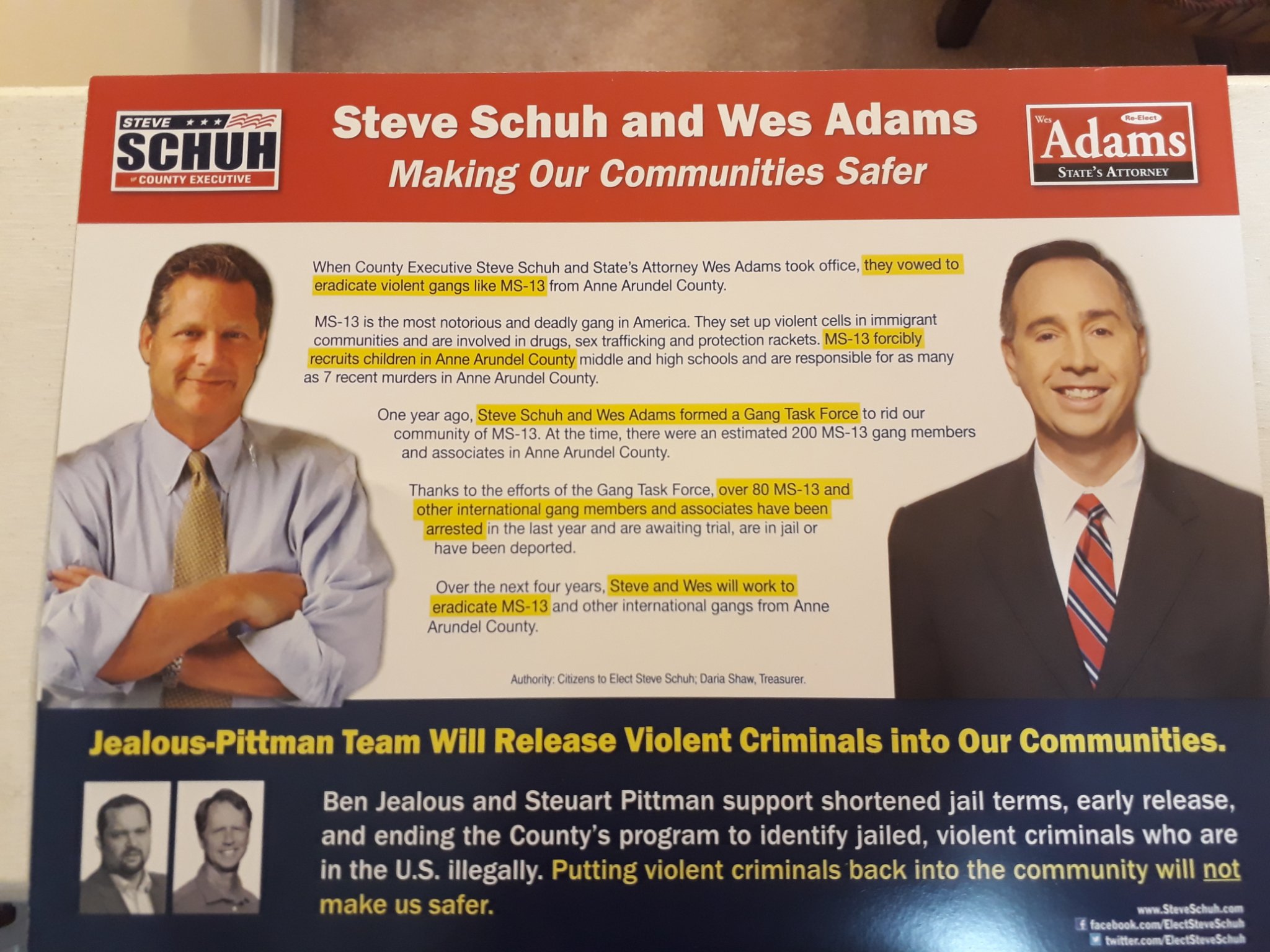

That was a common strategy among candidates who were defending cooperating with ICE. Steve Schuh, the incumbent Republican county executive of Anne Arundel County, sent out a mailer obtained by The Appeal: Political Report centered on MS-13 gang members that warned that Pittman, Schuh’s opponent, “Will Release Violent Criminals Into Our Communities.”

Pittman won by 4 percentage points, and he will govern with a newly Democratic-majority county board.

“We’ve got a lot of local problems to solve and holding ICE detainees is not one of them,” Pittman said in June. “Our biggest problem right now is beds for people who want drug treatment.”