Political Report

Looming Appointments Could Alter Florida Supreme Court’s Sentencing Outlook

Court issued a series of major youth sentencing and death penatly rulings in 2016. But its politics could soon swing dramatically.

In 2016, the Florida Supreme Court forced changes to the state’s death penalty statutes and signaled relief for hundreds who were first incarcerated as minors and have no realistic prospects for release.

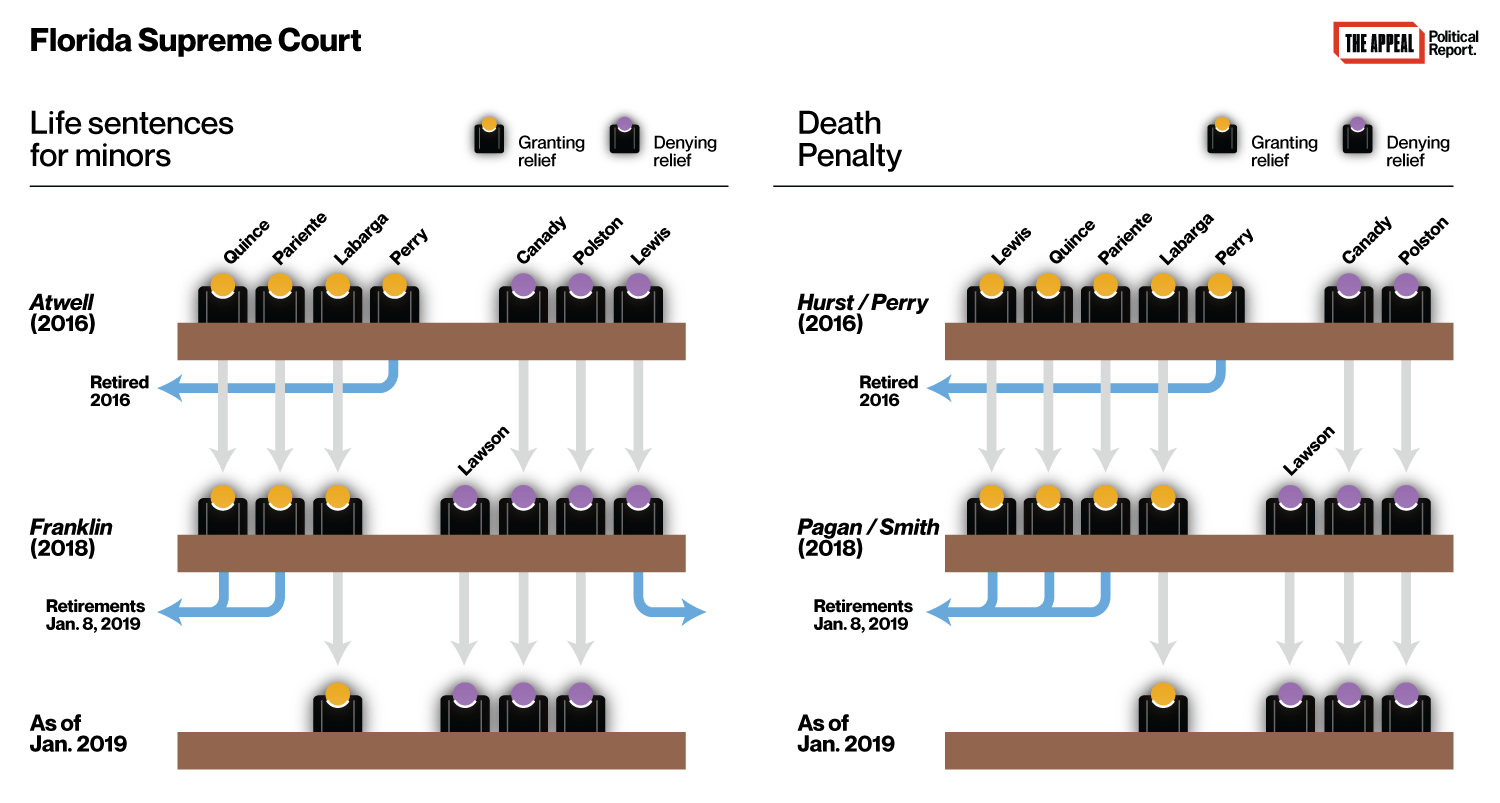

The court’s politics could soon swing dramatically. Three of the court’s seven justices (Fred Lewis, Barbara Pariente, and Peggy Quince) must leave next month. Incoming Governor Ron DeSantis will choose their replacements from a list of 11 nominees selected by the Judicial Nominating Commission. Nearly all eleven are Republicans. This is all on top of a replacement that occurred in late 2016, when Governor Rick Scott replaced the retiring James Perry with Alan Lawson.

This means that, come January, conservative governors will have appointed a majority of the court’s justices within a 25-month period, rapidly upending the odds of obtaining reform through the judicial system. Most of the outgoing justices sided with the petitioners in a series of major sentencing cases in 2016. Their replacements are unlikely to replicate these votes. “It will substantially change the focus and the rulings of the Florida Supreme Court,” Stephen Harper, the co-director of the Florida Center for Capital Representation, told me. “My overall outlook is very bleak.”

The impact of the transition from Perry to Lawson was felt this year in youth justice cases. Perry was in the 4-3 majority in Atwell v. State, a 2016 case in which the court held that the life sentence received by petitioner Angelo Atwell for a crime he committed at 16 offered him no meaningful chance of release even though it technically did include the possibility of parole. In her majority opinion, Pariente wrote that the “objective parole guidelines” that Atwell was sentenced under only made him eligible for release in 2130, and that this made his sentence “just as lengthy as, or the ‘practical equivalent’ of, a life sentence without the possibility of parole.”

But with Lawson’s arrival, the court flipped this year. In a 4-3 decision (Franklin v. State) issued in November, the court affirmed the lengthy sentences received by petitioner Arthur Franklin, who was 17 at the time of the crimes for which he was convicted. Pariente echoed the language of her own majority opinion in Atwell, except now it is the dissent she was writing. “The earliest Franklin could be released from prison based on existing parole guidelines is 2352,” she wrote. “There is no indication that Franklin has even a chance of being released before the end of his natural life expectancy.”

Once Pariente and Quince retire, just one of the four Justices in the Atwell majority will remain on the bench. “The Franklin case is an indicator that they will be far more conservative from here on even when it comes to kids,” Harper said.

Death penalty cases will be affected as well.

In 2016, the court issued two 5-2 decisions (Hurst v. State and Perry v. State) holding that the determinations involved in a death sentence must be rendered by juries (not judges) and that these juries must be unanimous. The Legislature amended state law to conform to the court’s decisions, which does solidify their legacy. But the Supreme Court, in deciding how to apply these rulings to already-existing death sentences, decided to only grant the motions of people sentenced after June 2002. Critics have denounced the partial quality of this retroactivity. But none of the Justices who dissented in the 2016 decision that created this cutoff (Asay v. State) will remain by next month.

Questions also exist about the fate of post-2002 sentences. When it did grant relief this year (for instance in Smith and Pagan), the court did so with 4-3 majorities. The three retiring justices were all part of these cases’ narrow majorities.

Harper predicted an increase in “the number of persons whose death penalty cases will be upheld.” But he also notes that the reforms codified by the legislature will still dictate sentencing in the future. “The good news is that given the requirement that now a unanimous jury makes the ultimate decision (and not a judge) there will be people who will not receive the death penalty whereas under the old sentencing scheme (pre-Hurst decisions) they would have,” he said.