Political Report

Two Candidates Run on Reform and Prevail in Mississippi's DA Elections

Criminal justice reforms have struggled in Mississippi, in part because of prosecutors’ lobbying. Will this change?

Criminal justice reforms have struggled in Mississippi, in part because of prosecutors’ lobbying. Will this change?

This article is part of the Political Report’s coverage of the 2019 elections.

When it comes to Mississippi’s sky-high incarceration rate and record disenfranchisement, district attorneys are on the front lines. Their decisions as to who to prosecute with what charges loom large.

On Tuesday, two candidates won DA elections on platforms that emphasize the urgency of seeking alternatives to prison.

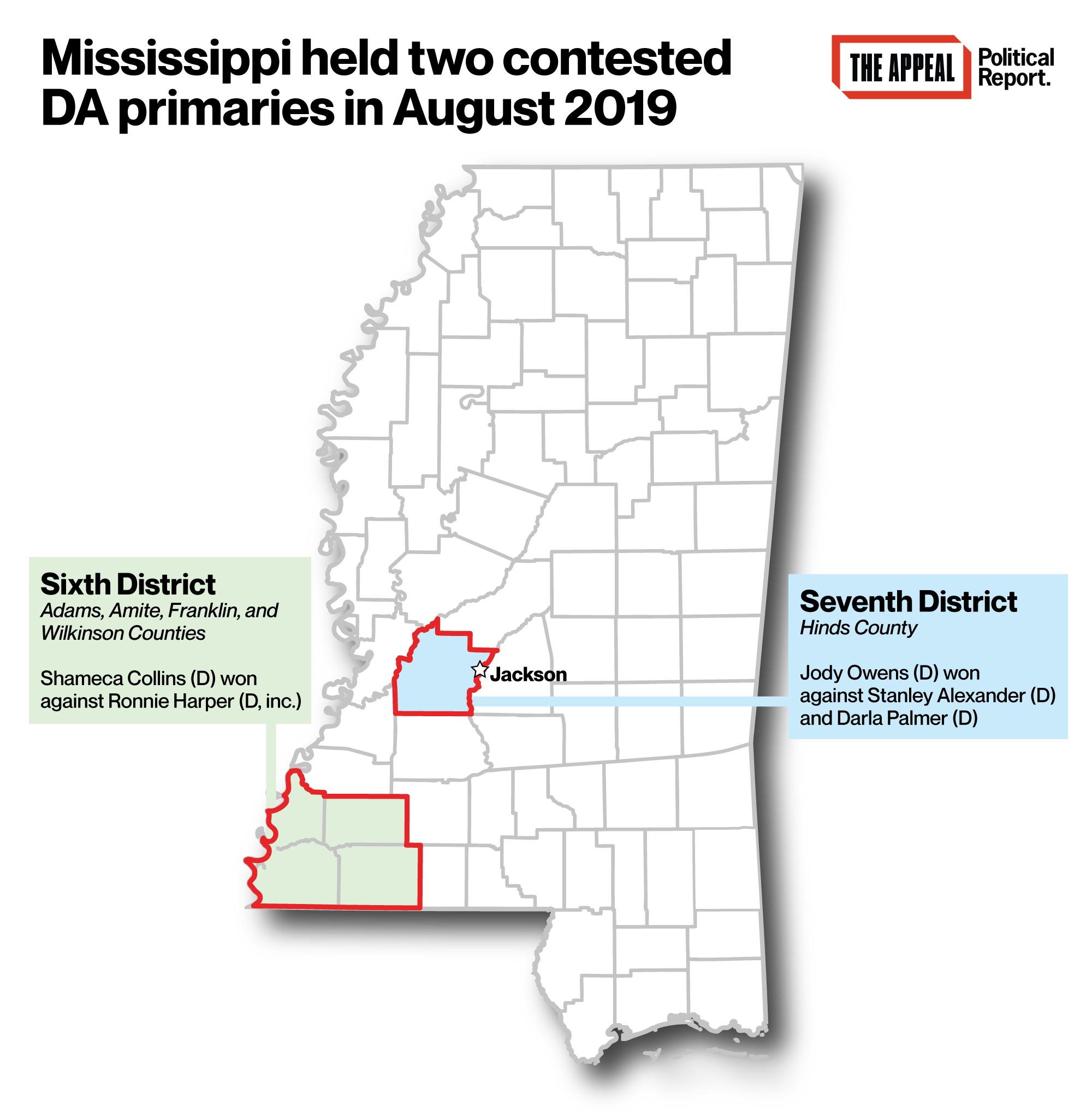

In the state’s southwest corner, Shameca Collins ousted DA Ronnie Harper in the Democratic primary of the Sixth District (Adams, Amite, Franklin, and Wilkinson counties). And in Hinds County (home to Jackson, the state capital), Jody Owens secured the Democratic nomination in the three-way primary to replace the departing Seventh District incumbent, Robert Shuler Smith.

Collins and Owens face no opponents in November’s general election. So they will be the next top prosecutors in their districts.

As managing attorney of the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Mississippi office, Owens oversaw lawsuits against the state’s alarming voting laws and detention conditions. “Our focus has been ending mass incarceration,” he told the Political Report last month. “When we ostracize individuals as we have in Mississippi … you’re creating a class system that district attorneys can do something about.”

Collins is a city prosecutor who led her platform with the need to promote alternatives to prison. “We have to support criminal justice reform,” she told the Natchez Democrat back when she launched her bid. “The duty of a prosecutor is not to convict, but to see that justice is done.”

She defeated a prominent figure: Harper was first elected DA in 1995, and has since vocally opposed reforms, for instance urging the governor to veto a bill expanding parole. He carried weight, as a past president and current board member of the Mississippi Prosecutors Association, the group that lobbies on behalf of the state’s DAs. “Mississippians are ready for a new direction on criminal justice that delivers more freedom and opportunity and far less incarceration,” Alesha Judkins, the Mississippi state director of FWD.us, told the Political Report. “The work ahead will be in translating that mandate to real policies that help real people.”

Theirs were the only two contested DA primaries this year. Very few of the state’s elections even drew multiple candidates this year. Scott Colom, a DA first elected in 2015 on a reform platform, is running for re-election unopposed this year.

So is Doug Evans, a DA whose misconduct was extensively documented by the podcast “In the Dark” (produced by American Public Media) and was the target of a Supreme Court ruling in June. But in Tuesday’s only contested elections, candidates interested in criminal justice reform made the most of the opportunity.

When the Political Report interviewed Owens last month, he criticized the state’s prosecutors for treating “more incarceration time” as “the only tool they have.” “There are a lot of individuals who don’t need to be in prison,” he said. “And there are certainly a lot of individuals in a state like Mississippi who don’t need to be in prison for the length of time that they are.” Instead, he explained that he would decline to prosecute marijuana possession, expand the use of restorative justice, and steer clear of the state’s harsh sentencing schemes for drug offenses. “We wouldn’t see ourselves seeking mandatory minimums or habitual sentences based on low-level drug possession charges, which could have been years if not decades previously,” he said, labeling the war on drugs a failure.

Owens made the case that such reforms would boost public safety, a connection that advocates are also drawing elsewhere. “You don’t maintain public safety solely by prosecuting individuals. To stop mass incarceration, one has to work in the community in a way which stops the cycle that feeds into this system,” he argued, referring to reentry programs and social services.

Collins’s public statements remain somewhat vague. Her website promises she will work for “fairness” and “transparency” and will “help build the community” rather than “destroy lives.” It also says she will “stand up to police misconduct” and “treat addiction as a medical issue,” the two most evocative statements in terms of her politics. But it mostly avoids pronouncements on concrete changes. Collins did not respond to a request for comment. On her website, as in the local press, she does indicate wanting to shift away from incarceration for some drug-related offenses. “Continuing to throw drug users into prison doesn’t solve the problem that we face,” she said. “We must look for new avenues to help these citizens get the treatment that they desperately need.”

Both Collins and Owens have mainly focused their promises of change on lower-level offenses. They confine reform to the first half of the overdrawn nonviolent/violent binary. This has long been a conventional staple of reform rhetoric, but some newer DAs like Boston’s Rachael Rollins and Philadelphia’s Larry Krasner have challenged it. “We can’t exclusively focus on nonviolent offenders,” Rollins said during her campaign last year.

Collins has also specified that her reform views apply to first-time offenders, another qualifier that would restrict its impact. “You can put programs in place that will reform our young men and women before they become another statistic,” she told the Nashua Democrat, but added, referring to “repeat offenders and those accused of committing violent crimes,” that “these programs will not be available to everyone. There are times when programs just cannot do the job.”

Still, if Collins and Owens bring their views into office, it could further transform the politics of law enforcement in Mississippi, and give some company to Colom.

Reform proposals have struggled in Mississippi in the past, in part because of the coordinated lobbying of reform-skeptic prosecutors. “Prosecutors don’t just drive or reduce incarceration in their own districts. They also have tremendous influence in state capitols where they weigh in on pending criminal justice legislation,” said Judkins. “Mississippi’s elected prosecutors have customarily opposed reforms to the state’s criminal justice system, but we are hopeful these newly elected reformers will join reform advocates at the capitol in calling for much needed pretrial and sentencing reforms.”

Elections in November could further grow the ranks of reformers. Michael Grace, who emphasized pre-trial diversion programs when he declared his candidacy, is challenging DA Kassie Coleman in the 10th District. And Jennifer Riley Collins, who was the ACLU of Mississippi’s executive director, secured the Democratic nomination for Attorney General. She was running unopposed in the primary, but faces a tough road in November. Her GOP opponent will be decided in a late August runoff.

Owens alluded to the impact that forming a statewide reform coalition may have in his interview with the Political Report, when he said he would promote voting rights when possible by filing charges that do not carry disenfranchising consequences instead of charges that do. “That will be one of my initiatives, with district attorneys who feel the same way,” he said. “If enough people are aware of this, we can circumvent their racist, Jim Crow-era law that continues to punish individuals for decades.”