Political Report

New Mexico Legislation Would Eliminate Felony Disenfranchisement

Can New Mexico provide a new model for ambitious voting-rights reform?

Can New Mexico provide a new model for ambitious voting-rights reform?

This article is part of a state-based series on disenfranchisement.

Voting rights were a core demand of the nationwide prison strike of 2018. “The voting rights of all confined citizens serving prison sentences, pretrial detainees, and so-called ‘ex-felons’ must be counted,” strike organizers wrote in their list of 10 demands. “All voices count.”

In New Mexico, groups like Millions for Prisoners New Mexico and the state’s ACLU affiliate have since stepped up their organizing against felony disenfranchisement. State law currently disenfranchises individuals serving a felony sentence, including when they are incarcerated, on parole, and on probation. “Voting is a First Amendment right, it’s our voice,” Selinda Guerrero, an organizer with Millions for Prisoners, told me. “It’s our voice in decisions that are being made that impact our lives and who represents us. These protections are so vital and important in recognition of just being human.”

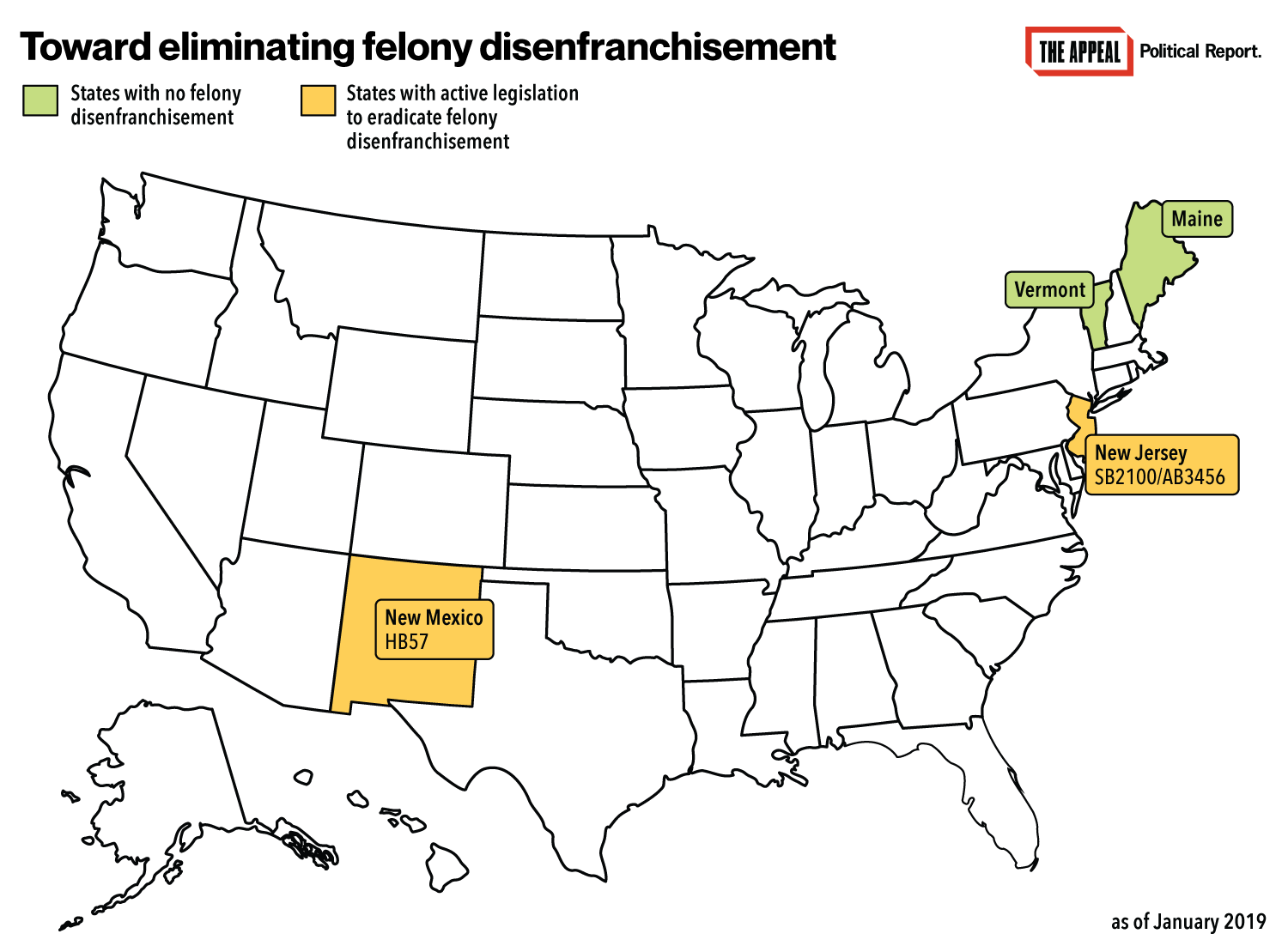

In December, state Representative Gail Chasey, a Democrat from Albuquerque, introduced legislation (House Bill 57) that would eradicate felony disenfranchisement in New Mexico. If the bill becomes law, New Mexico would join Maine and Vermont, the two states that do not disenfranchise people convicted of a felony and that enable people to vote while incarcerated.

Prior nationwide reforms have chipped away at the disenfranchisement system rather than eliminating it altogether. A law that came into effect in Nevada on Jan. 1 reduced financial disparities in who is disenfranchised, but the state retains harsh laws even by national standards. And when Governor Andrew Cuomo of New York expanded the voting rights of people on parole last year, he also left many citizens disenfranchised in addition to creating layers of rules and restrictions that impede eligible individuals.

Can New Mexico break that incremental mold and provide a new model for ambitious reform?

Democrats won full control of the state government this month for the first time since 2010. They significantly strengthened their hold on the legislature, and Michelle Lujan Grisham replaced Susana Martinez, a Republican who vetoed numerous criminal justice reform bills, as governor. “The new makeup of the state could be a good opportunity to push the envelope and get meaningful change,” Barron Jones, the Smart Justice coordinator of the ACLU of New Mexico, told me.

But that does not mean that all Democrats are on board with Chasey’s bill, at least not yet. State Representative Daymon Ely, who is the vice chairperson of the House Committee on Local Government, Elections, Land Grants & Cultural Affairs, told me via email that he believed that New Mexico’s current system was inadequate. “I think the quicker we can get citizens back to full participation in our democracy the better,” he said. But he also indicated that he was undecided about what reform should look like. (Committee chairperson Miguel Garcia did not respond to a request for comment, nor did Speaker Brian Egolf.)

Guerrero argues that reform should not leave incarcerated people behind. “They are citizens, they pay taxes through their commissaries, they have families that love them, and the vast majority will return to their communities,” she said. “Just taking a small community that is on probation or parole and enfranchising them, I didn’t feel like that’s what the list of [strikers’] demands was asking for. I do a lot of organizing with people behind the wall, and that wouldn’t meet their demands.”

“[Disenfranchisement] laws are designed to oppress folks,” Jones concurred. Jones was himself disenfranchised after being convicted of a felony. “Until I got my voting rights, it left me a place of anomie, like I didn’t belong.”

Jones said that voting is a way for incarcerated individuals to prepare for their re-entry into the community. “The vast majority of the people will one day be released to rejoin society,” he said. “We believe it’s very important they have a say in what society look like upon they return, and that can only happen if they have the right to vote.” Jones gave the example of a hypothetical referendum to increase the minimum wage. “Many people incarcerated are pigeonholed into these low-paying jobs” and they should therefore have a voice in the matter, he said.

New Mexico’s HB 57 is believed to be the first bill proposed since the 2018 prison strike that would eliminate felony disenfranchisement. The other state with active legislation to enfranchise people while they are incarcerated is New Jersey.

One prominent Democratic legislator who told me that he backed these advocates’ goal is state Senator Daniel Ivey-Soto, who sits on both Senate committees (the Rules Committee and the Judiciary Committee) that would hear Chasey’s bill. Ivey-Soto, who is the vice-chairperson of the Judiciary Committee, said he still needed to read the bill’s exact language before committing to supporting it. But he added that “philosophically, at this moment, I plan to vote for it, because I feel so strongly about what it means to be a citizen of this country.”

“It raises a provocative fundamental question,” Ivey-Soto said. “If we have tied citizenship to eligibility to vote…, how do we say, this is your birthright but it’s not? How do we say that with citizenship comes the ability to participate in the process fully?”

“Even if I have been convicted of a felony, I am still a citizen of this country,” the senator added. “The fundamental question is, what is the nature of a basic fundamental right, what is the nature of a birthright that attaches with citizenship or a right that attaches with naturalization?”

Ivey-Soto noted that the current system is a hindrance on the voting rights of even people who are technically eligible since they have completed all components of their felony sentence. That’s because state agencies do not keep full and proper records of who has completed a sentence, and because county clerks demand to see a Certificate of Discharge that many individuals have not received from their parole or probation officers.

“We have a lot of folks who currently qualify to register to vote who are being told no you aren’t eligible because the computer says you aren’t eligible unless you bring in this piece of paper that you never got,” Ivey-Soto told me. Jones of the ACLU said of this requirement to obtain a certificate of discharge: “It might be hard for [former prisoners] to engage the system that has mistreated them in many instances. To get your voting rights restored means you have to face the folks that have incarcerated you, and that’s a power dynamic that some folks are not ready to face.”

A similar power dynamic exists in any effort to get people who are already enfranchised to grant the right to vote to still-excluded individuals. And this dynamic now looms over the current push in New Mexico’s legislature. Ivey-Soto mentioned it as the main obstacle to HB 57. “This kind of legislation goes under the category of us-them legislation,” he said. “‘Us’ are talking about ‘them.’ And us-them legislation, oftentimes, you get surprised at how people vote on these things.”