Political Report

Colorado’s Teller County Cooperates with ICE, but Legislation Could Forestall This

A proposed bill would restrict the Colorado sheriffs’ ability to detain people for ICE and enter deals with the agency.

This article is part of a series on 287(g) contracts with ICE in states.

Sheriff Jason Mikesell has put Teller County at the vanguard of ICE cooperation.

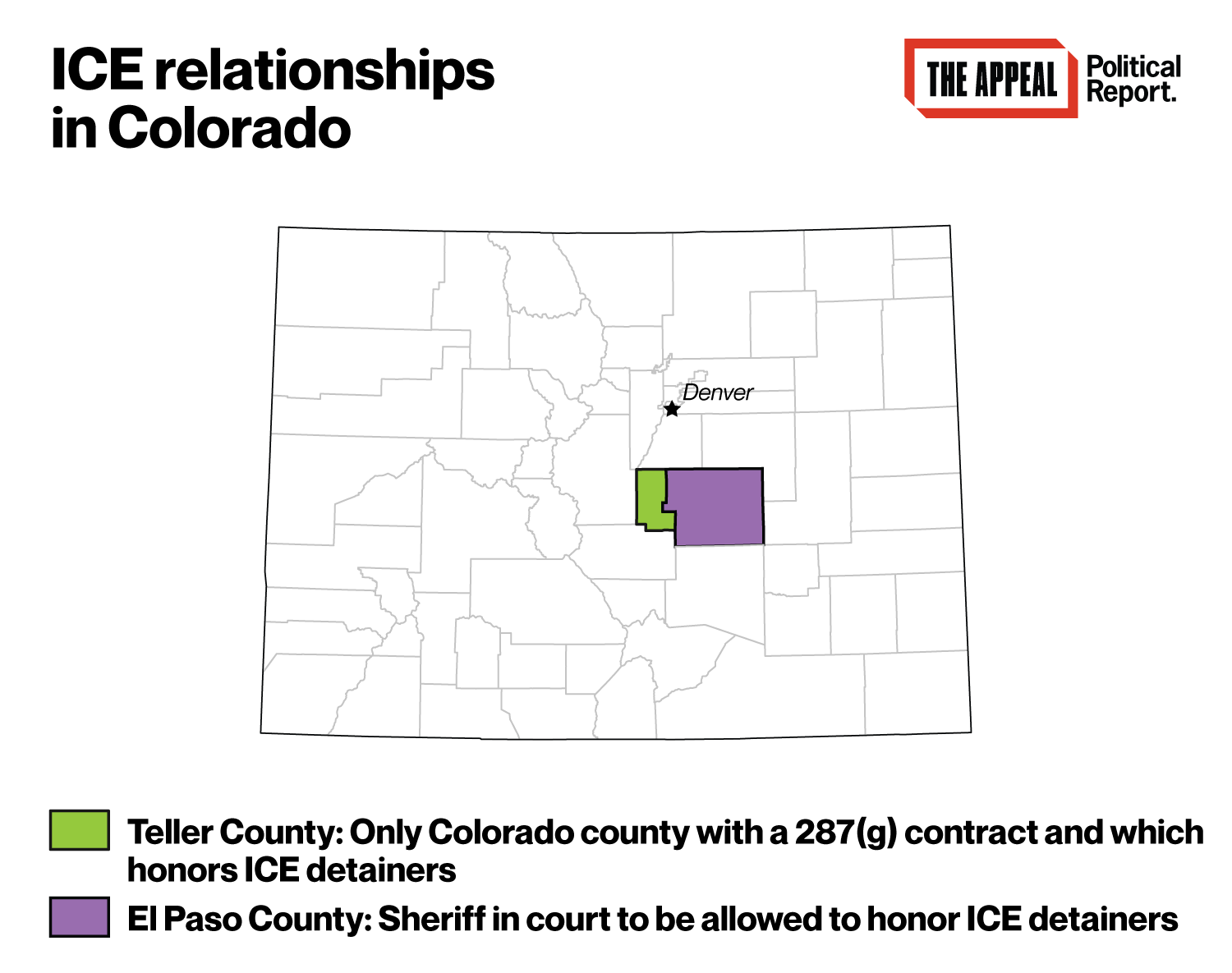

By the end of 2018, Teller was the only Colorado county to honor ICE detainers; these are warrantless requests that law enforcement continue detaining people past their release date, even if they have posted bail.

Mikesell then began 2019 by signing a 287(g) contract with ICE. Teller is now the only Colorado county that is participating in that program, which deputizes local law enforcement to research the status of people held at a county jail and to detain them over suspected immigration violations. Membership in 287(g) is unusual. Seventy-six jurisdictions nationwide have 287(g) contracts as of this week, and three of the program’s most populous member counties (North Carolina’s Wake and Mecklenburg, and Maryland’s Anne Arundel) quit as a result of the 2018 elections.

Critics of 287(g) say that local authorities should not be involved in enforcing immigration laws. “We should not be paying people or using our state to call and find something about somebody that we have no reason to know,” state Representative Adrienne Benavidez, a Democrat, told me.

Brendan Greene, the campaigns director of the Colorado Immigrants Rights Coalition, warned of the program’s impact on public safety. “When people know that contact with the sheriff will result in them being put in immigration proceedings, they will be afraid of calling the police and reporting crime,” he said. “This impacts women and survivors of domestic violence the most.” State Representative Leslie Herod agrees that 287(g) fosters mistrust toward law enforcement. “Communities shouldn’t be fearful of their local law enforcement agents and I think this will make them more fearful,” she said. “When you talk about what keeps local communities safe, it’s partnerships with local law enforcement not fear of local law enforcement.”

In addition, the ACLU of Colorado is questioning the legality of Mikesell’s 287(g) contract. “We believe that state law gives sheriffs no powers to enforce immigration law,” said Mark Silverstein, legal director of the ACLU of Colorado. He argued specifically that “Colorado sheriffs don’t have the authority to execute or serve federal immigration warrants,” which 287(g) asks them to do. “When someone is a pretrial detainee and posts bond, then the 287(g) deputy will purport to serve an ICE administrative warrant on that person and keep that person in jail even though they’ve posted bond,” he said. “State officers have no authority to execute those warrants.”

The Teller County sheriff’s office referred me to its public information officer, who did not respond to multiple requests for comment about why the sheriff entered the program and what he would respond to the questions about its legality.

When he applied to join, Mikesell wrote that it would help him fight “organized criminal activity by out of state cartels and illegal aliens who are taking advantage of Colorado’s recreational marijuana laws.” Mikesell has used a similar argument to justify his decision to honor ICE detainers.

“These are not people that you want as your neighbors,” he said in July in response to an ACLU lawsuit against the continued detention of a man named Leonardo Canseco Salinas. “These detainees have committed crimes in my community and throughout the United States, such as sexual assault, drug manufacturing and attempted homicide, and many other crimes that cause our citizens to live in fear.” But an article in Westword pointed to the mismatch between this language and the circumstances of Canseco’s case since he was arrested for stealing $8 at a casino.

Greene told me that if Mikesell’s “true intent is to fight crime, then he should have a true bond with everyone in community. If people in your community are afraid to speak to you, there’s no way you can have the trust you need in your community to fight crime in the first place.” Benavidez also disputed this idea that identifying civil immigration violations helps fight crime since there already are avenues (ones that demand a judicial warrant) to detain people for criminal activity. “I don’t think our law enforcement should be entering in 287(g) agreements to turn over people that ICE thinks are a threat,” she said. “If they think they’re a real threat, we have laws to arrest them based on criminal violations.” Benavidez made the same point about detainers, namely that ICE is claiming an exceptional power to arrest “on civil grounds or non-substantiated criminal grounds, based on administrative requests.” She called this “an anomaly that has been carved out by ICE that there is no good reason for.”

Benavidez has filed House Bill 1124 to end such anomalies and to restrict local cooperation with ICE. HB 1124 would bar local law enforcement from spending public funds to help enforce civil immigration laws, from signing contracts that mandate deputies to provide assistance, and from honoring an immigration detainer that is not backed by a judicial warrant. “I’m hopeful it will pass,” Benavidez said. “Many people at least in my party have run on some of the tenets.” Colorado Democrats now control the governorship and both chambers of the state legislature.

Benavidez said HB 1124 would bar counties from joining 287(g) or renewing their contracts, but that it would not terminate existing agreements. But Silverstein of the ACLU told me that a bill can be crafted in such a way as to bar sheriff’s deputies from following through on a contract even if it technically remains in effect. He explained that “a state statute could forbid them to carry out identified functions” like “serving ICE administrative warrants” and “carrying out arrests for civil violations of federal immigration law,” and this “despite the existence of such an agreement.” Silverstein believes that these functions are already illegal, but that legislation could clarify the matter.

HB 1124 would also clarify whether sheriffs can legally honor detainers. In 2013, the legislature repealed a state law that required local law enforcement to notify ICE when they suspect an individual of being undocumented. In the ensuing years, and in the face of legal pressure by the ACLU, all Colorado sheriffs settled on a policy of not honoring ICE detainers. The County Sheriffs of Colorado, which represents the state’s sheriff’s departments, said in an unsigned letter: “Outside of legally recognized exigent circumstances, we cannot hold persons in jail at the request of a local police officer or a federal agent. To do so, would violate the 4th Amendment to the US Constitution.”

But the sheriffs of El Paso and Teller counties broke this consensus and began honoring ICE detainers, the former in 2017 and the latter in 2018. The ACLU of Colorado promptly filed lawsuits in both counties—and the subsequent judicial rulings produced bifurcated outcomes.

In August, District Judge Lin Billings Vela denied a preliminary injunction against a man’s detention in Teller County. She wrote that Colorado lacks “a statute prohibiting law enforcement from cooperating with federal immigration officials.” She did not issue a final judgment, and Silverstein said the parties have since agreed that the case should be dismissed without prejudice. But this enables Mikesell to continue honoring detainers at the moment.

Then in December, the ACLU won a legal victory in El Paso County when District Judge Eric Bentley barred Sheriff Bill Elder from honoring detainers. (This case is headed to the state Court of Appeals.) Bentley took the inverse approach of Billings Vela, citing a lack of statutory authorization: “No Colorado statute currently authorizes sheriffs to enforce civil immigration law or even to cooperate with its enforcement. Under these circumstances, absent a statutory grant of authority, the Court is reluctant to create an arrest power through inference.”

HB 1124 would add an explicit prohibition, barring “a law enforcement officer from arresting or detaining an individual solely on the basis of a civil immigration detainer.”

Mikesell became sheriff in 2017 when he was appointed by the county’s commissioners. He secured a full four-year term at the polls in 2018, when no one ran against him in either the GOP primary or the general election, which means that he has yet to face an opponent. He is next up for re-election in 2022.