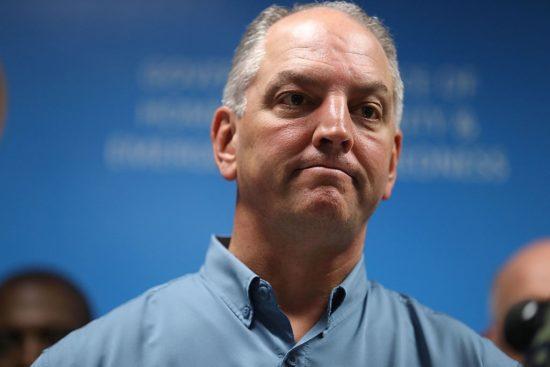

Louisiana Attorney General May Run For Governor By Fearmongering Over Criminal Justice

Attorney General Jeff Landry has taken a number of extreme positions on policing and sentencing in response to reform.

Louisiana Attorney General Jeff Landry said recently that he will most likely run for governor next year, mounting a challenge to Democrat incumbent John Bel Edwards, who has brought sweeping criminal justice reforms to the state and significantly reduced the prison population during his first term as governor.

“There’s no doubt if I run I will beat John Bel Edwards, and you can tell him I said that,” Landry told a reporter last month.

Edwards’s efforts to reform Louisiana’s notorious criminal justice system will most likely be a major flashpoint of the gubernatorial campaign. Though the two were elected to the same executive branch in 2015, Landry—a former sheriff’s deputy and police officer—has fought the governor’s policy agenda constantly, particularly over criminal justice issues.

During his nearly three years in office, Edwards has overhauled the state’s criminal justice system, to the point where Louisiana no longer holds the title of most incarcerated state in the nation. In 2017, he signed the most comprehensive criminal justice reform bill in the state’s history, reducing sentences for nonviolent offenses while encouraging the use of alternatives to prison. As of this year, the state’s prison population has dropped by over 7 percent. The effort has widespread bipartisan support from law enforcement, community organizations, and other advocates.

But Landry has stoked fears that reform is unleashing dangerous criminals on the streets. In a column in The Advocate in March, Landry and Senator John Kennedy called Edwards’s legislation a “disaster.” The two Republicans cited an example of a man convicted of burglary who then robbed several businesses after he was released through the new sentencing laws. He “was able to commit his latest string of crimes because Louisiana Gov. John Bel Edwards’ Louisiana Justice Reinvestment Act freed him early from prison,” they wrote.

The man was, in fact, released just two months earlier than his original sentence called for, according to Ken Pastorick at the Department of Correction. Nevertheless, they wrote, the Louisiana Justice Reinforcement Act “should be called the Louisiana Prisoner Release and Public Safety Be Damned Act.”

Through this lens, Louisiana’s criminal justice reform could face a grim future under a Landry administration. He would most likely strengthen efforts by other Republicans to roll back or repeal the reform.

In an extreme move that breaks with his own party, the attorney general has also recently come out against a November ballot initiative that would require juries in the state to reach unanimous verdicts to convict in felony cases. Louisiana is just one of two states that allow split-jury verdicts thanks to a Reconstruction-era rule explicitly intended to disempower Black jurors. (Oregon, which joined later, is the other state.) The state Republican Party and powerful conservative groups including the Koch brothers’ Americans for Prosperity are all supporting the initiative to make jury verdicts unanimous.

Landry did not respond to a request for comment from The Appeal and declined an interview with local press. But when asked about his position on split juries, his chief deputy said Landry believes “the non-unanimous jury law has a positive effect on the criminal justice system in Louisiana. We believe it makes for quicker and easier administration of the system.”

Landry took it upon himself to create a task force of state agents in New Orleans to tackle the rising rate of violent crime without coordinating with city officials. In a little under a year, the task force made at least 16 arrests, mostly for drug offenses, with significant controversy over its legal right to patrol the city. The chief of police told Landry that the attorney general actually has no jurisdiction to make arrests within a municipality, and Mayor Mitch Landrieu claimed that by not coordinating with the city police, Landry was endangering officers. The task force was disbanded roughly 11 months after its creation.

Landry has also been Louisiana’s most vocal critic of sanctuary cities and has targeted New Orleans, despite the mayor’s insistence that the city is fully compliant with federal immigration law.

Jim Craig, director of the New Orleans office of the Roderick & Solange MacArthur Justice Center, said Landry’s convictions about Edwards’s criminal justice reform package and his efforts in New Orleans point toward his end goal of higher office.

“It’s pretty clear that almost all of his criminal justice positions are posturing to secure the Republican nomination for governor next year,” Craig said. “He’s not trying to get votes from people in New Orleans. He’s trying to play off against New Orleans, which is a pretty racially coded message on his part, so that people outside New Orleans in rural Louisiana will see him as standing up against a majority Black and Black-run city.”

Landry and Edwards have also publicly sparred about other criminal justice issues, including the future of capital punishment in Louisiana. Edwards has avoided sharing his personal view on the death penalty, saying his job is to carry out the law. But since he took office, he has put executions on hold, citing the unavailability of lethal injection drugs and laws preventing the state from using other methods of execution. Louisiana has 71 inmates on death row but has not carried out an execution since 2010.

Landry, a capital punishment supporter, has said if that’s the case, the state should change the law. In mid-July, Landry wrote a letter claiming Edwards has not been aggressive enough on enforcing the death penalty. He claimed that because of Edwards’s inaction, “a large and growing number of victims’ families suffer in legal limbo waiting for justice to be carried out.”

The attorney general suggested legislation that would allow the Department of Corrections to choose other methods of capital punishment when drugs are unavailable, including hanging, firing squads, and electrocution. But during the legislative session, Landry didn’t take any action to move forward with those alternatives.

He also threatened that he will stop defending the state in litigation over its lethal injection protocol because he claims Edwards isn’t trying hard enough to acquire the necessary drugs. After a request by state officials working for Edwards, a judge recently extended an order blocking all executions in the state for 12 more months.

Landry has also earned enemies for his position on a state law banning strippers under the age of 21. He has argued that young dancers are prone to “secondary effects” of working at strip clubs, but in a federal lawsuit challenging the law, dancers have claimed that the law is overly vague, broad, and discriminatory. A federal judge sided with the dancers in 2016, but Landry appealed the ruling to the Fifth Circuit.

But Craig insists that Landry’s statements on criminal justice issues are largely aimed at a potential campaign for higher office, as he has done little to follow through with many of his threats and it’s unclear whether he would take action on justice issues if he were elected governor.

“Clearly he wants to distinguish himself from the Republican field,” he said. “As they say some places, he’s all hat and no cattle.”