‘I Feel Trapped’: Treating Drug Use in the COVID-19 Pandemic

Social distancing orders are a necessity, but they create a host of new problems for people in treatment for substance use disorders.

There’s a saying that the opposite of addiction isn’t sobriety, it’s community. For the nearly 20 million Americans who have substance use disorders, the social distancing and quarantines of COVID-19 have just made the hard job of recovery much harder.

Synn Stern, a nurse at New York Harm Reduction Educators’ (NYHRE) drop-in clinic in Harlem, has a close-up view. Before the pandemic, an estimated 40 to 80 people came through the battered gray doors of the clinic every day, making it a swirling hub of people picking up medication for substance use disorders, HIV, and hepatitis C; getting supplies for safe drug use; using the bathroom; and just stopping by to hang out. But with over 85,000 confirmed cases of COVID-19 infections nationwide and New York State being the disease’s epicenter in the U.S., the doors of the drop-in are now shut. Stern and her co-workers fear that the pandemic’s ripple effects on the health of the city’s most vulnerable residents is just beginning.

Although quarantine and isolation orders go a long way toward preventing the spread of coronavirus, they present a staggering host of new issues for people struggling with substance use disorders—particularly those who attend opioid treatment programs (OTPs). Methadone clinics, a kind of OTP, require most patients to come in every day to pick up their dose of methadone, sometimes at a specific and inflexible time. Patients may need to bring their children along if schools have closed, or stand in line for hours outside because the clinic has reduced its maximum occupancy level— potentially exposing themselves and their loved ones to the virus. (Because of the way COVID-19 attacks the respiratory system, people with substance use disorders can be particularly vulnerable to the disease. They are also more likely to have insecure housing and unreliable access to medical care, which can increase the possibility of a severe case.)

Healthcare officials are not unaware of these challenges. In an attempt to mitigate risks of exposure at OTPs, the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration has updated its normally inflexible rulings on how many doses of methadone a patient can take home. States may give patients who are deemed “stable” up to 28 days worth of medication to take home. Patients who are deemed “less stable” can take home up to 14 days of medication. Stability is defined by federal criteria, and one of the influencing factors is the safety of one’s living situation.

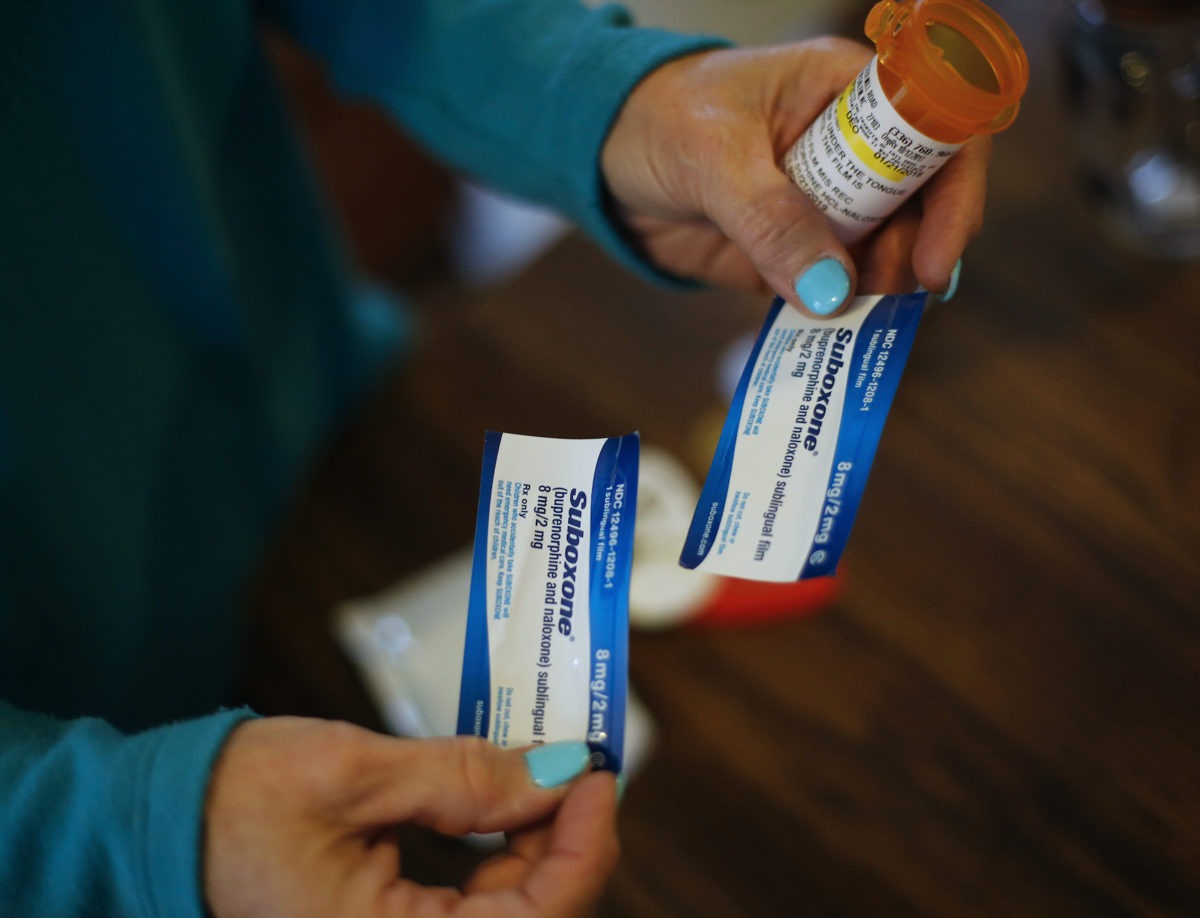

Even if a clinic was able to give out one month’s worth of take-home doses to all of its patients, Stern explains, that creates a new problem: secure storage. Her clients are intimately familiar with the dangers of trying to keep medication safe while living precariously. She recounted the story of a homeless patient whose medications for seizures, antidepressants, and the opioid-treatment Suboxone were all stolen at once. Some of her homeless clients have actually requested that they pick up their medication from the clinic each day—not because it’s required, like in a methadone clinic, but as a precaution to keep it safe.

Across the country, states are scrambling to figure out how to get people medication without making them come into clinics, and how to keep that medication safe. Pennsylvania and Washington have updated their guidelines to let people take home more doses at a time. Many states are recommending teleconferencing, virtual check-ins, and suspending previously mandated urine tests. California’s harm reduction-focused Bridge Program released guidelines that include extending prescriptions of the opioid-treatment drug buprenorphine to the maximum possible length and using pharmacy home delivery. Indiana’s Division of Mental Health and Addiction is exploring solutions to the problem of safe storage by giving out methadone in lock boxes.

But each measure made to help people stay more isolated creates new vulnerabilities. Martha Ruiz, one of NYHRE’s senior case managers, worries that quarantine orders—and the fear, isolation, and uncertainty that come with them—will cause a rash of relapses and overdoses across the country. She also worries that an overloaded medical system will relegate people struggling with substance use to second-class status—deprioritized in hospitals and clinics in favor of less stigmatized patients. Stern is similarly concerned that the coronavirus could cause new outbreaks of HIV or hepatitis C, as people become unable to access preventive medications and clean, safe supplies for drug use.

But the greatest concern for them is that organizations like NYHRE aren’t just a means for people to get healthcare: they’re people’s touchstones and family systems. One NYHRE client who has been visiting the office six days a week for the last 10 years said, “They help me keep my feet grounded in terms of my substance abuse. They see me. Now I feel trapped. I feel cornered.” While thousands of Americans are worrying about how to make rent in a collapsing economy, some of the country’s most vulnerable residents have already lost the places where they feel safe.